Norse myths are having a moment. Or should I say another moment; one of a long chain of moments, in fact, beginning in the primordial soup of the oral tradition of storytelling in Iceland and Scandinavia. This mythology is old; old and very tenacious. First chronicled by scholars and historians some centuries after the Christianisation of Scandinavia, it tells of the creation of the world from the flesh of a slaughtered giant; of the rise of Asgard, the stronghold of the gods, and of their struggle against the forces of evil; and it predicts the eventual death of the gods in a final battle, Ragnarók, in which all of creation will be destroyed. It also tells of the exploits of some of the most complex, entertaining, funny, flawed and, yes, human characters ever to lift a hammer in battle against the enemy.

Norse gods do not have the remoteness of the Olympian gods, the grandeur of the Greek heroes (at least in bowdlerised modern versions) or the strangeness of the Egyptian pantheon. Norse gods are oddly familiar. Their powers may be godlike, but their motives are all too human. They make terrible life choices. They fall in love with the wrong people. They succumb to jealousy and lust. They can be fearful, careless, mean, resentful or downright stupid. Their myths are part soap opera, part fantasy, with a good deal of vaudeville thrown in.

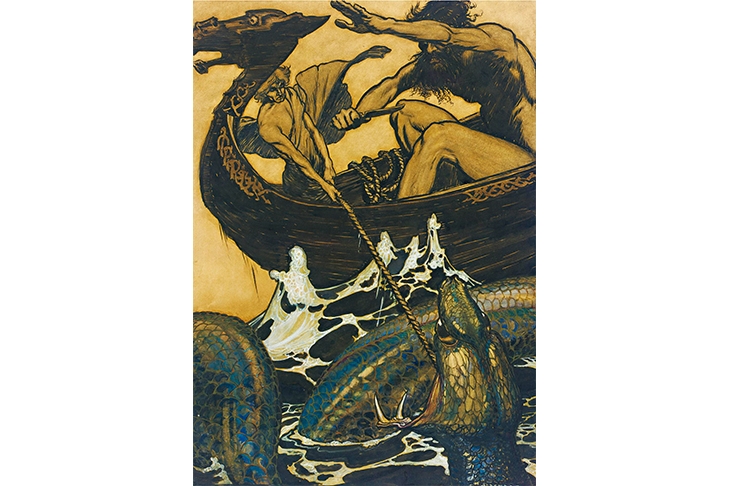

Perhaps it is this familiarity that has made the Norse myths so enduring. Certainly, the amount of source material that has survived is relatively small, most of it taken from the anonymous group of early skaldic poems known as the Poetic Edda, and the Prose Edda, compiled by Snorri Sturluson in about 1220. But what these myths may lack in volume, they make up for in impact. The Norse myths have influenced countless writers and artists across the centuries, from Tolkien to Wagner, Rackham to Alan Garner, propelling the gods of the Vikings as far as Japanese manga and the Marvel universe.

Many of these works have taken the gods far out of their natural sphere. Neil Gaiman’s 2001 novel American Gods relocated them to modern-day America and pitted them against the new gods of wealth, change and the media. Aspects of their legends have appeared in several of Gaiman’s other works, including Sandman and Odd and the Frost Giants. And following the recent translation of American Gods to screen, the publication of Gaiman’s Norse Mythology may not come as too much of a surprise. But to a younger readership more familiar with the gods of Marvel than with those of the Eddas, and with so many books in print in which the original myths have been changed and subverted, it comes as a welcome opportunity to revisit the traditional stories and to understand their significance in the broader context of literature.

As such, Gaiman’s Norse Mythology offers little by way of subversion. Like the Norse Myths of Kevin Crossley-Holland (1993), it is a fairly conventional account of the principal stories outlined in the Prose Edda, from the birth of the first being from out of the primeval ice to the chaos of Ragnarók, and the hope of a new world. There is no attempt to impose a more linear structure on the myths. That has been done many times elsewhere, and in this retelling, the inconsistencies and eccentricities that form part of the charm of the original source material are reproduced mostly without comment, in a clear and accessible prose. Gaiman’s voice is engaging; often quirkily humorous, and the spaces between the myths (as essential, perhaps, as the myths themselves) are explored with a gentleness close to reverence.

Unlike Snorri’s Edda, there is nothing pompous or grand here, nor any hint of preaching. Instead, it’s easy to imagine oneself reading these stories to a child, or having them read to you by a friend. With the deftest of touches, the characters are once again brought to life: Odin the Allfather, grim and unfathomable; Thor the Thunderer, loyal, strong, but not particularly bright; Loki, the Trickster, rebellious, perverse and self-destructive; Freyja, the Goddess of Love and War; Skadi, the Snowshoe Huntress, vengeful, solitary and cold. The author’s affection for the characters shines out from every page, and the narrative, always crisp and direct, combines an adult’s insight with a childlike sense of wonder at the magic of it all; the heroes, the monsters, the giants, the runes. Best of all, the stories remain as fresh and appealing as they were when I first discovered them.

Thus, the myths I loved as a child can be passed to a new generation, to be reinvented anew. For stories that cannot be retold are destined to be forgotten; and every generation must rediscover these myths for themselves, and take from them whatever they need.

Comments