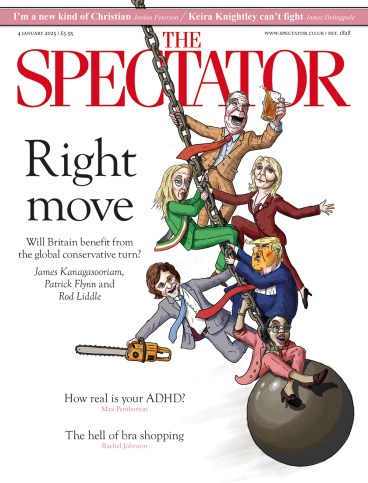

New year predictions are always rash, but it feels as though one aspect of the story of 2025 can already be written. The gap between the economic fortunes of the US and Europe will continue to widen – and Britain will be trapped very much on the European side of the divide.

In three weeks’ time the US will have a new leader, one who will unashamedly put the interests of US business first. Donald Trump’s threat of punitive tariffs may or may not be realised (as in his first term, it could prove to be a negotiating tool to press for the removal of restrictions on US exports and an end to currency manipulation by China). But several things are certain. A Trump-led US will not be adopting a growth-destroying social democratic model. It will continue to pursue a policy of cheap energy and of energy self-sufficiency, and will not be strangling its industry with net-zero targets. Elon Musk will oversee a sharp contraction in the size of the federal state, with tax cuts to follow. Unproductive government officials will be sacked, not treated to four-day weeks.

How different Britain’s prospects look. We have a government which preaches growth and yet seems to understand nothing of the conditions in which it thrives. Ever since the Labour party began to accuse the Cameron government of ‘austerity’ for daring to attempt to balance the public finances, it has seemed to operate under the belief that only the public sector can generate economic growth. It sees the private sector, by contrast, as there to be plundered. Entrepreneurs are not innovative and hard-working people whose talents and appetite for risk-taking create jobs and wealth; they are merely the fabled ‘broad shoulders’ who can be tapped again and again for revenue.

There is nothing new about the increasing divide between economic growth in the US and UK. It has been evident all century. To use figures from the Maddison Project – a Dutch database which compares long-term growth rates across countries, adjusting for both inflation and purchasing power parity (i.e. taking into account local living costs) – the US economy in 2022 was 50.6 per cent larger than in 2000. Britain’s economy, by contrast, grew 38.4 per cent. What may look like minor differences in annual growth year by year add up to very consequential differences in wealth. As the Centre for Economics and Business Research put it this week, if current trends continue for a further 15 years, by 2039 Britain will be closer in terms of GDP per head to Guyana than to the US. We will end up a middle-income country rather than a high-income one.

That is if current trends continue. An all-too-possible alternative is that the growth gap between Britain and the US widens. Previously, the British and US economies have tended broadly to suffer the same bumps and enjoy the same bounces. In 2001 the UK even managed to avoid a shallow recession which afflicted the US.

If Britain wants to remain a rich country, it is going to require a serious change in direction of policy

Yet Britain now seems to be generating a recession all of its own. The economy failed to grow in the third quarter of last year and went on to shrink by 0.1 per cent in October. There are good reasons for this. The government spent its first four months in office floating the prospect of every tax rise under the sun. Then, when the Budget was delivered on 30 October, it contained one of the most damaging tax hikes to business imaginable: a rise in employers’ national insurance combined with a sharp lowering of the threshold at which employers’ NI becomes payable, from £9,200 to £5,000 – the latter adding £600 to the cost of employing a part-time worker on £10,000 a year. NI is, as Rachel Reeves herself described it before taking office, a jobs tax. While the rise does not take effect until April, it has already damaged confidence, with many businesses stopping or reducing hiring.

Does anyone really believe the Chancellor’s assurances that there will not be further pain to come? There are few signs of the government making significant cuts to public spending, and public sector wage rises have added substantially to present and future spending. At this rate Reeves may well be back in the autumn having discovered another black hole, this one entirely of her own making. There will undoubtedly be another round of hefty tax rises to try to fill it.

Meanwhile, Ed Miliband’s doctrinal target of achieving almost entirely carbon-free electricity by 2030 promises little relief for UK industry, which already must cope with the highest commercial electricity prices in the world. Miliband’s promise that more wind energy will bring down those prices looks somewhat forlorn given that Britain has one of the highest proportions of wind in its energy mix. Other than opening parts of the green belt to housing developers there is little sign of deregulation, either.

If we want to remain a rich country, it is going to require a serious change in direction of policy, including a large shift from an unproductive public sector and the encouragement of the private sector. There are few signs that the present government is prepared to countenance what will be necessary. But sooner or later, Britain is going to have to decide: does it want to carry on being one of the wealthier countries, or are we happy to slip down into the global second or third division, following the same path as other once fantastically wealthy civilisations such as Egypt, Greece or the great seafaring power that was Portugal? The answer should not be difficult.

Comments