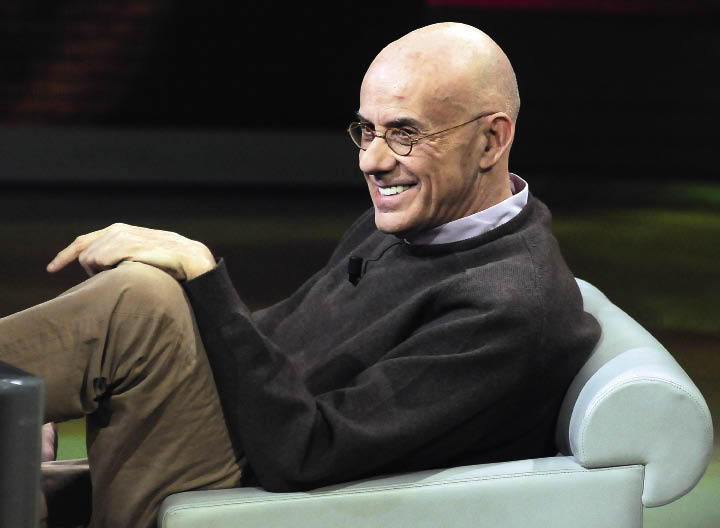

By now, the crucial details of James Ellroy’s life, particularly the unsolved murder of his mother when he was ten years old, may be known better than his books. He emphasised the connection himself when The Black Dahlia, based on a more famous unsolved murder, became a bestseller, constructing a ‘demon dog’ persona to promote the novels which followed. Finally, in his memoir, My Dark Places, Ellroy investigated his mother’s death, and seemingly offered her a benediction, but as he said ‘closure is a preposterous concept’.

He had rejected his mother before she met her end, preferring his slick but shallow father’s indulgence. This youthful cruelty is the root of the Hilliker (his mother’s maiden name) Curse. Through two marriages and countless fantasies, he now traces an intense adolescent romanticism, his need to protect women. He sees himself getting what he wants, then discarding it, paying huge psychic costs. What this reveals is the immense strain of having ‘over-sold himself to the world’; the impossibility of being true to both his public persona and his inner romantic.

‘My books felt like film noir’, Ellroy says, but his women aren’t femme fatales, nor is he the slightly stupid lug such women manipulate. One of his LA cop friends once explained him by saying that as a child his ‘eyes saw more than his soul could take’. The Hilliker Curse (Heinemann, £16) traces a boy’s attempts to embrace that soul by finding its soul-mate, but the prospect of such closure seems, if not preposterous, elusive.

Comments