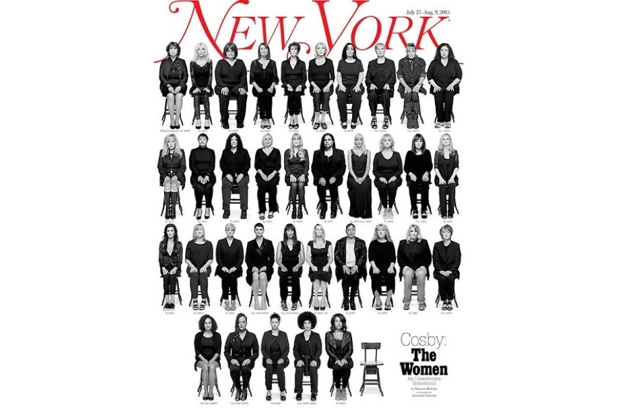

Last week, New York magazine ran a front-cover photo of 35 of the 46 women who have accused actor Bill Cosby of sexual assault. The feature inside includes individual interviews with each woman, but argues that ‘the horror is multiplied by the sheer volume of seeing them together, reading them together, considering their shared experience’.

The collation of these women’s accusations follows intense public interest in Cosby’s alleged misconduct, triggered last year when the comedian Hannibal Buress declared ‘you raped women, Bill Cosby’ during a routine. The New York feature is not an attempt to bring Cosby to justice, or even to challenge the statute of limitations that impedes any potential legal process against him. Instead, it’s about creating a kind of sorrowful sisterhood, a gathering of alleged victims, and in the process it, like so much Cosby commentary over the past year, runs the risk of denting a key principle of all democratic societies: innocent until proven guilty.

In recent months, Cosby has become a global figure of suspicion and contempt. He has faced public vilification and has been described in the British media as a ‘monster’, ‘evil’ and a ‘sexual predator’. He’s been the subject of a slew of media whispers and Twitter chatter about him being a serial rapist. And all of this has happened without hard proof that this one-time avuncular comedy actor is guilty of the crimes he’s accused of. One case was brought against Cosby in 2004; but it was settled out of court, with no conviction.

Have we ditched the idea of a fair trial in a court of law? In the Cosby case, alleged sexual assaults are effectively being tried on social media, with a jury of feminist tweeters passing judgement. This should worry anyone who cares about justice and individual liberty.

Yes, Cosby seems to be an unpleasant man, or at least not the man many people thought he was. And there is the possibility that the allegations against him are true, or at least have elements of truth – after all, Cosby admitted to giving a woman Quaaludes, a nervous-system depressant, in the 2004 case. But we simply don’t know. And we must exercise caution. Yet the press coverage of accusations against Cosby, and the internet reaction, perverts the normal approach to justice, by implying he is guilty until he can prove himself innocent.

The internet has become Cosby’s courthouse. His online judges have turned women who would once be known as accusers or complainants into ‘victims’ – a slip in language that has worrying implications. If we are serious about justice and about the rights of the individual against the state, then we have to defend the principle that you cannot be branded guilty until you’ve had a fair, rigorous trial. Otherwise a pointed finger is enough to condemn.

Legally, Cosby is innocent, or rather ‘not guilty’, and thus, in vilifying him as a predator, the media and online commentators are placing themselves above the law. The rules of justice – such as innocent until proven guilty, the statute of limitations, the right to be tried by a jury of our peers – exist in western legal systems for one very important reason: to protect individuals from the arbitrary judgements of those with authority and power. Those getting their rocks off by posting memes or comments about Cosby being a rapist imagine they are striking a blow for women and for justice. But the opposite is the case: they’re damaging justice, and weakening the protections that ought to be enjoyed by all of us, women and men.

Comments