‘I hope the day will never come when I shall neither be the subject of calumny or ridicule, for then I shall be neglected and forgotten’, is how Samuel Johnson greeted the news that James Gillray had caricatured him as Dr Pomposo. In Georgian London, a caricature was a fast-track to celebrity. And, as described by one contemporary observer, the print shop window was ‘the temple of fame in grotesque’.

Gillray was chiefly responsible for this. When he emerged on to the print publishing scene in the 1780s, the British art of ‘caricatura’ – an Italian import – was in its infancy. It grew up fast. Gillray, who had misspent part of his youth as a strolling player, invented a wittily scripted visual theatre of the absurd, uniting brilliant draughtsmanship with a fluency in mirror writing that rivalled Leonardo’s. It was a killer combination.

I emerged from the exhibition breathless with astonishment at the daring of his attacks

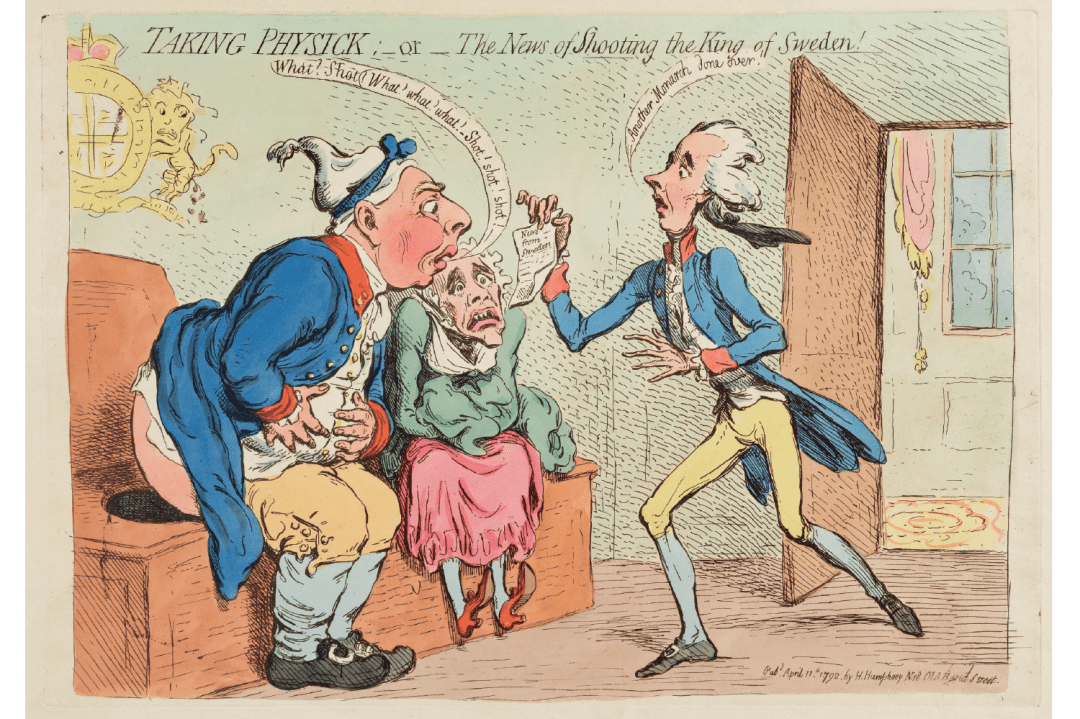

For modern audiences, the problem with Gillray is that without a grasp of the politics of the period, his best shots are liable to fly over their heads. For the current Gillray exhibition at Gainsborough’s House – the first in 20 years – his biographer Tim Clayton has sensibly focused on the most famous of his cast of characters. Nobody – apart from Nelson – is spared. Lèse-majesté was his stock-in-trade: in ‘Taking Physick; or The News of Shooting the King of Sweden!’(1792) George III and Queen Charlotte are shown sitting on a double commode as William Pitt announces some bowel-loosening news.

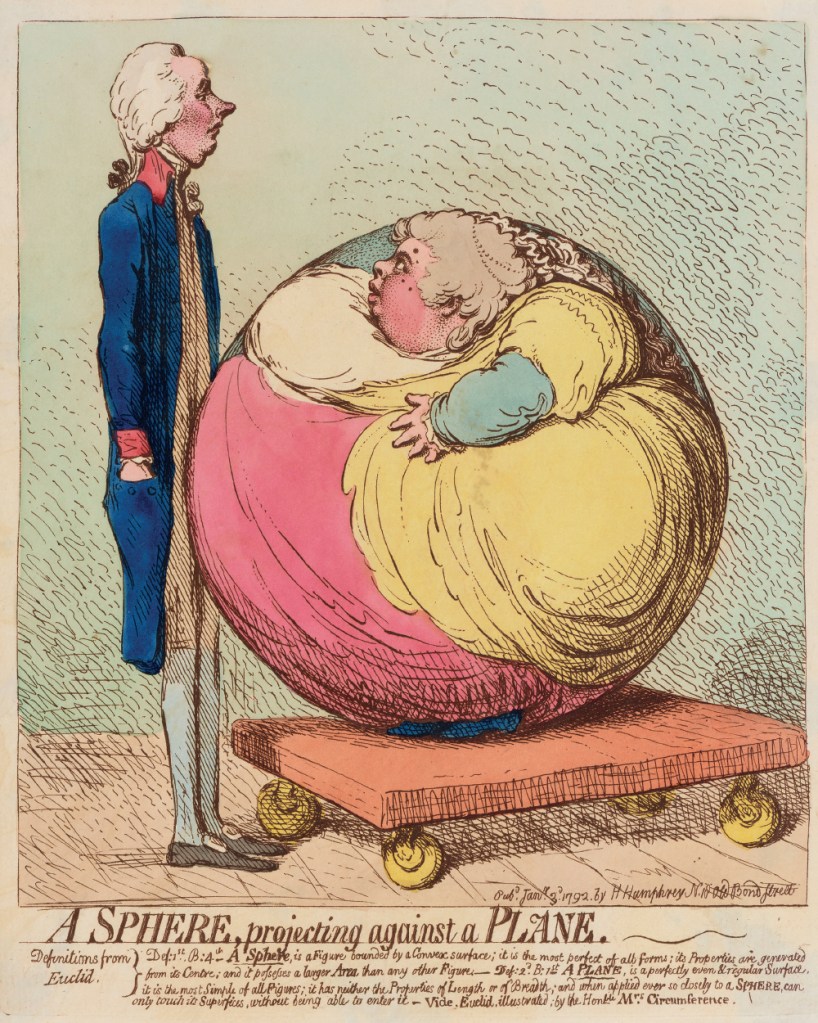

For an audience that, pre-modern mass media, had little idea what public figures looked like, Gillray rendered his favourite targets instantly recognisable by judicious exaggeration: the corpulent Prince George straining the buttons of his waistcoat and breeches in ‘A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion’ (1792); the ascetic Edmund Burke stripped down to specs, nose and bony hands in ‘Smelling out a Rat; or The Atheistical-Revolutionist disturbed in his Midnight “Calculations”’ (1790); the lanky Pitt contrasted with the rotund Albinia Hobart in ‘A Sphere Projecting against a Plane’ (1792), illustrating Euclid’s principle that a plane, ‘when applied ever so closely to a sphere, can only touch its Superfices, without being able to enter it’ (see below). The bachelor prime minister whom Gillray dubbed ‘the bottomless Pitt’ was famously virginal.

Gillray worked for various publishers, but from the 1790s almost exclusively for Hannah Humphrey, lodging above her shop in St James’s and caricaturing the influencers of the day for her female clientele. By then, political satirists were feeling the heat. A month after the publication of ‘Taking Physick’ a royal proclamation clamped down on seditious writings; Gillray retorted with ‘Vices overlook’d in the New Proclamation’ (1792) showing the royal family indulging in avarice, drunkenness, gambling and debauchery: ‘Vices, which remain unforbidden by Proclamation… in place of the more dangerous Ones of Thinking, Speaking & Writing.’ Touché.

Gillray invented a wittily scripted theatre of the absurd

But in January 1796, Gillray was charged with blasphemy for drawing an innocuous parody of the Wise Men. After an interview with George Canning, who had been badgering him for a caricature, the charge was dropped; 18 months later he was on a government pension.

Had he sold out? Although a liberal at heart, Gillray was always even-handed in dishing it out and, in an age before PR companies, caricaturists were political pen-slingers for hire. Initially sympathetic to the French revolutionaries, after the outbreak of war with France he was recruited as a highly effective government propagandist: his image of ‘Little Boney’ as a vertically challenged tyrant has stuck (the Corsican was actually above average height). But his famous cartoon of Napoleon and Pitt carving up the world between them, ‘The Plumb Pudding in Danger; or State Epicures taking un Petit Souper’ (1805), was a general indictment of geopolitical greed.

Brought up, like William Blake, in the Moravian evangelical Protestant church, Gillray was a born dissenter, a depressive and a workaholic. His relentless rate of production took its toll: no creative brain could keep up that stream of ideas without consequences. Following the loss of his two lead characters, Pitt and Fox, in 1806 and at risk of losing his sight, he began to lose his mind. In July 1811, he tried to throw himself from the attic of Humphrey’s shop and had to have his head prised from between the window bars by a chairman from White’s. Four years later he was dead, aged 58.

Two centuries on, a collection of Gillray cartoons remains a wild ride. I emerged from this one breathless with astonishment at the daring of his attacks and the admirable sang-froid with which his subjects suffered them. Martin Rowson and Steve Bell, who both cite the Georgian cartoonist as a major influence, were censored or sacked by the Guardian last year for far less. The Georgians had a nerve. Are we losing ours?

Comments