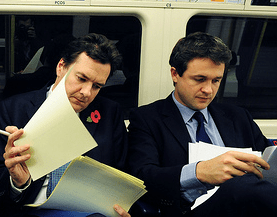

In today’s Telegraph, I profile Rupert Harrison, chief economic adviser to George Osborne and the man who’ll do more than anything else (including his boss) to shape next week’s Budget. In the British political system, special advisers are given very little attention — even though the best of them are more influential than the average Cabinet member. The Treasury’s vast power, assembled by Brown, is still there. That can’t be said for Osborne: he spends half his time in Downing St, and is sufficiently detached from the Budget process that he felt able to take a couple of days’ holiday in America last week to jump in the motorcade and press some presidential flesh. Perhaps he assumed, as Reagan said, that the deficit is big enough to look after itself. And anyway, Harrison was with him — and Harrison is in charge.

Harrison is a fiscal conservative, which he defines as being skeptical about both the high-debt policies advocated by Labour and the tax-cutting agenda advocated by the likes of David Davis (and yours truly). You can’t really say that he pulled Osborne and Cameron in any particular direction. He has put flesh on the bones of the Cameroon economic agenda sketched out by Oliver Letwin during the 2005 leadership campaign. Davis was advocating JFK-style pro-growth tax cuts, so the Cameroons attacked them as ‘unfunded tax cuts’, which had hitherto been a Labour phrase. All this explains Osborne’s reluctance to cut taxes in 2012.

But, when Osborne needed some tax-cutting ballast in opposition it was Harrison who provided it: specifically, the proposed (and, later, abandoned) inheritance tax cut credited with stopping the 2007 election. His favourite Chancellor is Geoffrey Howe, not Nigel Lawson. And it’s Howe’s 1981 budget — which raised taxes to help address the deficit — that he regards as being the most influential of that decade.

You can hazard a guess at the background of anyone senior in the Cameron project, and Harrison is no exception. He was head boy at Eton then read PPE at Magdalen (97-01), where even left-wing academics regarded him as one of the brightest students in years. Bright enough to realise that PPE wouldn’t equip him for a career in economics. He joined the Institute for Fiscal Studies and simultaneously studied for an economics doctorate at UCL, before joining Team Osborne in 2006. The coming Budget would perhaps be more radical if Harrison had gone to the University of Chicago for his postgrad, as the IFS has no interest at all in low-tax, supply-side economics. The IFS follows an age-old law: that any organization which relies on taxpayers’ money will almost never make the case for less tax.

Anyway, Harrison joined Osborne in 2006 and now, aged 33, he is perhaps the most powerful person you’ve never heard of. On £80,000, he’s the best-paid adviser outside Number 10. He’s softly spoken, and is dispatched across government to solve problems that may break out between the Treasury and other departments. I’ve spoken to Cabinet members who regard him as being far more valuable to speak to than Osborne — who will, anyway, defer to Harrison on economic matters. The feeling in Whitehall is that, if Harrison agrees something, it’ll pass. In opposition, he laid out a plan to eliminate the structural deficit over a five-year parliament. This was precisely the position adopted in government, affected by coalition not one bit. This plan was abandoned in the Pre-Budget Report, however, when Osborne faced a choice between more debt or more savings — and chose the former.

Harrison’s reputation in Whitehall explains why Ladbrokes has him at 50-1 to be the next leader of the Conservative Party, even though he did not join his colleague Matthew Hancock in seeking one of the safe seats which became available after the expenses scandal. For what it’s worth, I’d be amazed if he does seek office. Politics is not an all-consuming passion for him. Whether his definition of ‘fiscal conservatism’ is enough to get Britain out of this hole is a very open question. But if you ever wonder how Osborne gets away with being a part-time Chancellor, this is the answer: it’s really Harrison’s show.

Comments