To read this long-overdue and welcome biography of Peter Shore is to undergo a journey from Labour’s eurosceptic heights in the 1960s to its demise as a party of the nation state in the 1990s. Titled Labour’s Forgotten Patriot, patriotism is a theme which constantly recurs and, to a considerable extent, defined Shore’s political life.

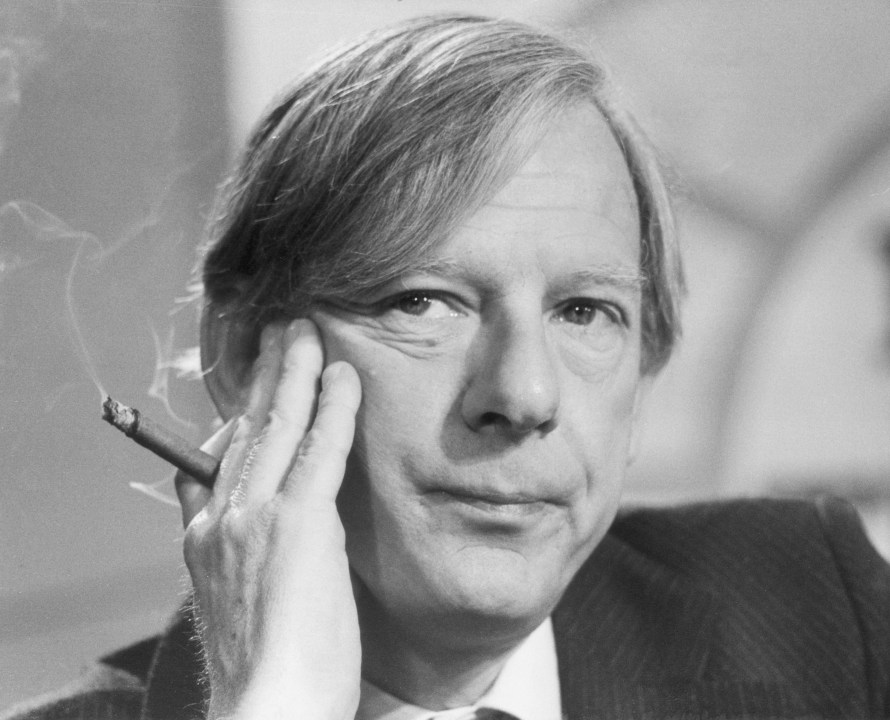

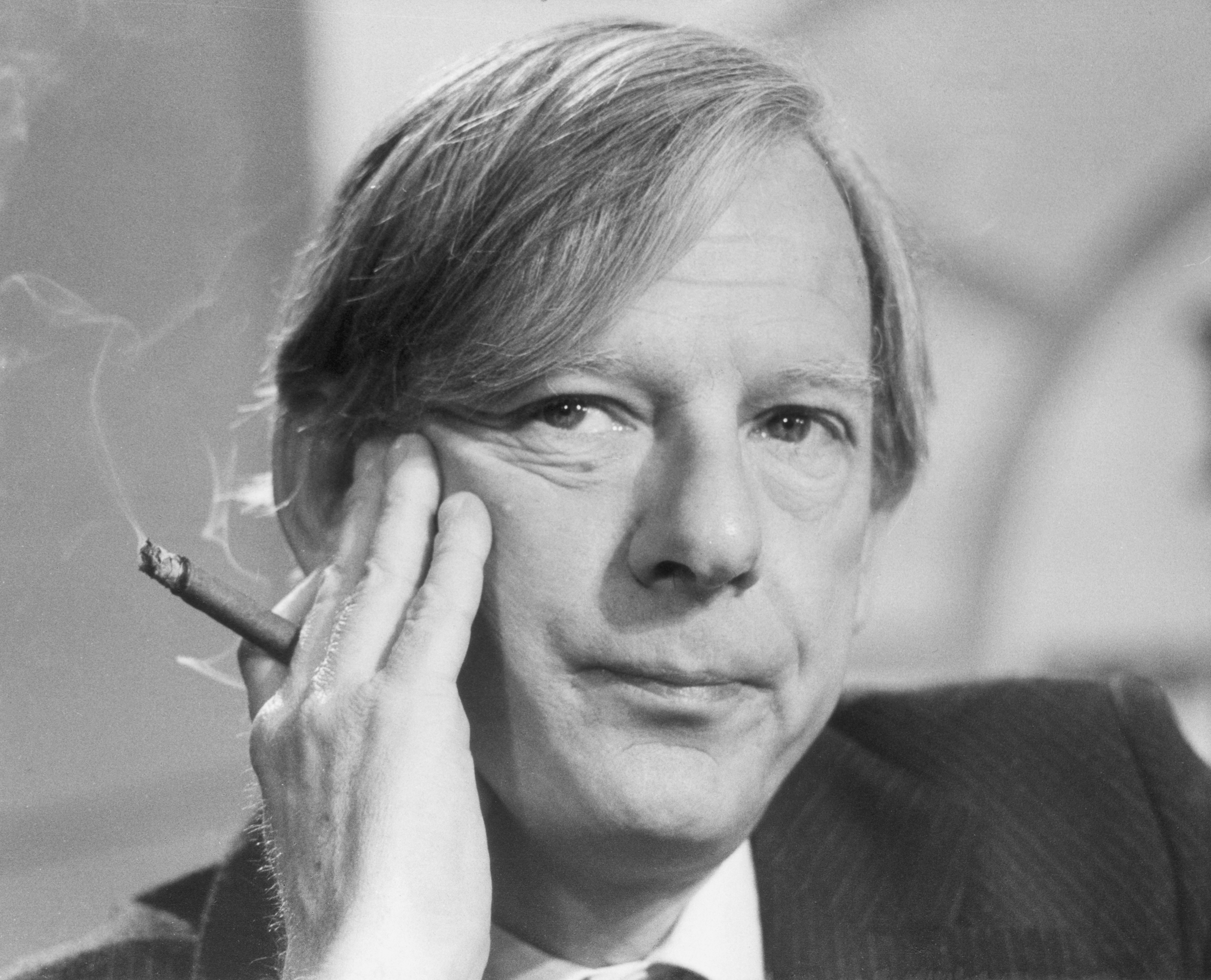

Peter Shore has been a rather neglected figure. This is odd since he had considerable influence over Labour politics for two decades and was probably the staunchest defender of Britain’s independence. A Cambridge Apostle, rising star in the Labour Research Department of the 1950s and part author of three consecutive Labour general election manifestos, Shore came to national prominence as parliamentary private secretary to Prime Minister Harold Wilson (Shore almost certainly wrote the famous ‘white heat’ speech). This close association with Wilson’s inner circle caused Denis Healey, in characteristically cutting style, to describe Shore as ‘Harold’s lapdog’.

A donnish, reserved and quite detached character, he was never destined to rise to the very top of politics

It was under Shore’s influence and that of fellow eurosceptics such as Benn, Foot and Douglas Jay – together with their leader Hugh Gaitskell – that Labour maintained its opposition to membership of the European Community throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It was the Tories of that generation who were seduced by the European project and who, as adherents of ‘managed decline’, lacked belief in Britain’s capacity to govern itself. The book is a fascinating insight into a time, unrecognisable now, when to be a politician of the left, one could naturally coexist with deep-rooted patriotism. Left-leaning politicians could also, as Shore did, argue for tougher sentencing of criminals. The book is a window into the post-war period in which Labour produced a generation of able and serious thinkers. Whether you agreed with them to not figures such as Shore, Crosland, Benn and Foot compare positively with Labour’s present crop of identity-obsessed, superficial political pygmies.

The book has many notable highlights. Shore was one of the very few parliamentarians – possibly the only one – who bothered to read the Treaty of Rome. For weeks this colossal document lived on his bedroom floor, his wife Liz referring to it as a trip hazard (in more ways than one…). While Shore’s economic socialism moderated over the years, he recognised, correctly I think, that the nation has objectives which are different from and sometimes opposed to those of industry. And as an economic nationalist, Shore perceptively pointed out that acceptance of EU membership by Labour politicians flatly contradicted the Keynesianism that they professed to hold. There was no point, in his view, of electing an interventionist Labour government if EU membership fettered and constrained its economic programme.

The book outlines Shore’s limitations as a party politician. A donnish, reserved and quite detached character, he was never destined to rise to the very top of politics, despite trying for the Labour leadership. Occasionally the authors’ obvious admiration for their subject gets the better of them. For instance, it is unlikely, I think, that Shore’s proposals for urban renewal would have prevented the Toxteth riots of the 1980s. Their cause was deep-rooted.Examples of Shore’s patriotism pepper the book. After the invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982, Shore was quick to criticise what he regarded as colonialism and fought against any idea of abandoning ‘people of British descent’ to the mercy of the Argentines.

Later, throughout the 1980s, Shore watched Labour’s gradual drift into universalism and the politics of grievance and individualism but was unable to arrest its course. Somehow, the patriotic Labour tradition of which he was part had become unacceptable within the party. The mistake of progressives, Shore argued, had been to confuse internationalism with the desire to build a European state – the two were quite different. He ‘boiled with rage’ on hearing of proposals to introduce EU passports. Nevertheless, Shore continued to argue his case, starkly asking, ‘where does Europeanism end and something like treason begin?’ In particular, he understood the fundamental need for democratic self-governance, stating: ‘Independence is the first of all freedoms: freedom not to be occupied, not to be colonised, not to be coerced by the power of another state.’ It was the Labour party that moved not him.

From the standpoint of Labour’s recent disintegration, Shore’s viewpoints are strikingly prophetic. As early as 1983 he spotted the folly of assembling a ‘rainbow coalition’ of minorities as a political strategy after Labour’s huge 1983 election defeat. An opponent of the New Right’s emphasis on individualism, Shore believed that a unified sense of community was the essence of socialism. Winning elections, therefore, depended on convening national solidarity which involved making a broad appeal to the majority rather than pandering to a series of minority grievances. It was not possible, he argued, to assemble a winning platform ‘if you try to enlist the single issue, egoism and selfishness of particular groups.’ How right.

Ultimately, it’s for his position on Europe that Peter Shore will be remembered. Despite his shyness, he was an inspirational rhetorician and his magnificent address in 1975 at Oxford Union stands as perhaps the greatest ever eurosceptic speech by a British politician. As Sir Christopher Audland commented in relation to the UK’s early negotiations for EU entry, the original sin of europhiles was to fail to level with the British people about what membership actually entailed. Heath, who uncomfortably looked on to that speech in 1975, had misled the public about three things – the costs of membership, the consequent loss of sovereignty and the loss of democratic control.

Peter Shore was right about many things: the need for a successful party of the left to be unifying rather than divisive in nature; the need for successful societies to foster solidarity rather than selfish individualism; and the need for nations to govern themselves. Shore was a highly influential figure in the post-war Labour party. He is fondly remembered by some and his legacy richly deserves this important biography.

Comments