Throughout her memoir, Nicola Sturgeon emphasises her achievement in becoming the first female first minister of Scotland. While that achievement should not be underestimated, I’m sure I’m not the only woman who wishes she made a better job of it.

In her political afterlife, as in her political life, she evades real scrutiny

It’s not just her determined blind spot on the implications of self-identification for women’s rights which emerges from this memoir, but also the fact that her much trumpeted support for women, including those under attack in the public forum, seems not to extend to those who dare to disagree with her.

There is widespread recognition that Nicola’s legacy is marred not just by the self-identification fiasco but by other notable policy failings in the fields of education, the NHS, drug deaths and public transport (ferries and roads). Not to mention her failure to advance the raison d’etre for her political career, Scottish independence, beyond the point to which her predecessor took it.

Yet she has remarkably little to say about these issues in her memoir.

For example, on her failure to close the educational attainment gap she claims that it took her a while to realise the role played by child poverty. This is hardly rocket science. Besides, the child poverty payment which she finally introduced in February 2021 was a policy which she initially dismissed out of hand when it was first presented to her by Alex Neil five years earlier in February 2016. But she doesn’t mention that.

Clearly, she considers her handling of the Covid pandemic to be her greatest triumph. She cites the exhaustion it induced as one of the reasons for her resignation and says she came close to a breakdown in the wake of her evidence to the Covid inquiry. Yet, the chapter on Covid is curiously silent on some of the biggest concerns which have come to light since her daily broadcasts to the nation ended. Care home deaths merit a brief mention but there is no analysis or justification of strategy that led to them. Nor does she even attempt to justify the deletion of her WhatsApp messages despite her promise to a journalist to keep them.

Nicola is very keen to remind us, repeatedly, of her love for books. But for all her reading, this book, like her speeches, is curiously short on big ideas or indeed literary references. Except for a very superficial treatment in the opening chapters there is little insight into why she is a Scottish nationalist and which political theories she espouses.

Even where she does attempt to address difficult issues such as her sexuality, she dances around the issue and the reader is left not quite sure what she is trying to say. The confusion has not been cleared up by her media interviews during the publicity storm surrounding the book.

Reflections on life as a woman in politics is one of two themes which dominates this memoir. The other is a thorough traducing of her predecessor and one-time mentor. Alex Salmond is clearly living rent free in her head except he isn’t because he’s dead and some think that’s in no small part due to the treatment he endured at her hands. Not content with the fact that he’s now gone and can never again be a threat to her, large parts of this book are devoted to further besmirching his character.

Before the book was even published, Salmond’s political friends and independent observers like the highly respected former Green MSP Andy Wightman and the journalist David Clegg, were able to debunk some of the allegations against him. These include the ludicrous notion that Salmond himself might have been the author of the leak which led to the media storm around allegations that he was a sex pest and that he was opposed to gay marriage despite him having introduced it as first minister. The minister he entrusted with doing so, Alex Neil, claims that Salmond handed him the equal marriage brief because, ‘Nicola didn’t want to do it any longer as she was fed up with it.’

Despite her efforts to heap further opprobrium on Salmond, Sturgeon scorns the idea that there was any conspiracy to do Salmond down and that she was involved. She states that there was neither evidence nor motive and leaves it at that. Thus, she avoids addressing the evidence of conspiracy that has been adduced by others – some of which has been revealed under parliamentary privilege by David Davis MP and Kenny MacAskill (former MP and leader of the Alba party) – including the existence of WhatsApp messages by her husband, Peter Murrell and other close aides in which the suborning of evidence against Salmond was discussed alongside how best to pressurise the police to act.

Ironically the motive for removing Salmond from the political scene emerges in the glaring resentment of him displayed in her book. In addition, anyone who’s been paying attention to Scottish politics knows that he was manoeuvring to make a leadership comeback after she suffered one of her biggest setbacks with the loss of 21 SNP MPs in the 2017 general election.

In contrast to her constant attacks on Salmond, her memoir is remarkably light on any explanation as to why she was unable to capitalise on the extraordinary legacy which he bequeathed her. Independence support was at its highest level ever and an explosion in SNP membership and support led to the party capturing almost 50 per cent of the vote at the 2015 general election.

There is very little discussion of her strategy to capitalise on the opportunities afforded to advance the cause of independence during the Brexit saga and Boris Johnson’s premiership. She sums the situation up by saying independence could not be advanced because the British government would not grant her the permission to hold another referendum. However, she does not explain what if anything she tried to do about this apart from repeatedly banging her head against the brick wall of their refusal.

She also omits any reference to the viciousness with which she and her supporters shut down any attempt to discuss or debate a Plan B.

Likewise, there is no discussion of what advantage she might have tried to parlay in the 2017-2019 when her 35 SNP MPs were close to holding the balance of power at Westminster. Presumably because there was no discussion at the time. I know because I was there and was pilloried for trying to initiate such a discussion.

Indeed, the reader will search in vain for anecdotes about the sort of tortured policy debates in cabinet or at the party’s national executive committee one normally reads about in political memoirs, because, under Nicola’s leadership, such discussions were neither encouraged nor tolerated.

She writes that as soon as Boris Johnson became PM she knew there would be another general election. There is no mention of the opportunity that was afforded to take Johnson down after the UK Supreme Court had ruled his prorogation of parliament unlawful. Indeed, the unlawful prorogation, the most extraordinary upheaval in modern British constitutional history, does not even merit a mention. I can only assume that this is because she failed to appreciate its significance, rather than because I was partly the author of the court victory.

On the scandal surrounding the SNP finances we hear little except about the impact the police investigation has had on her and her joy at her ‘exoneration’. Further discussion, she tells us, cannot happen because of the charges against her husband. How convenient. I guess we shall have to wait for another day to hear why she so determinedly shut down legitimate questions from party members and NEC representatives about the whereabouts of a £600,000 independence referendum fund that was supposed to be ringfenced.

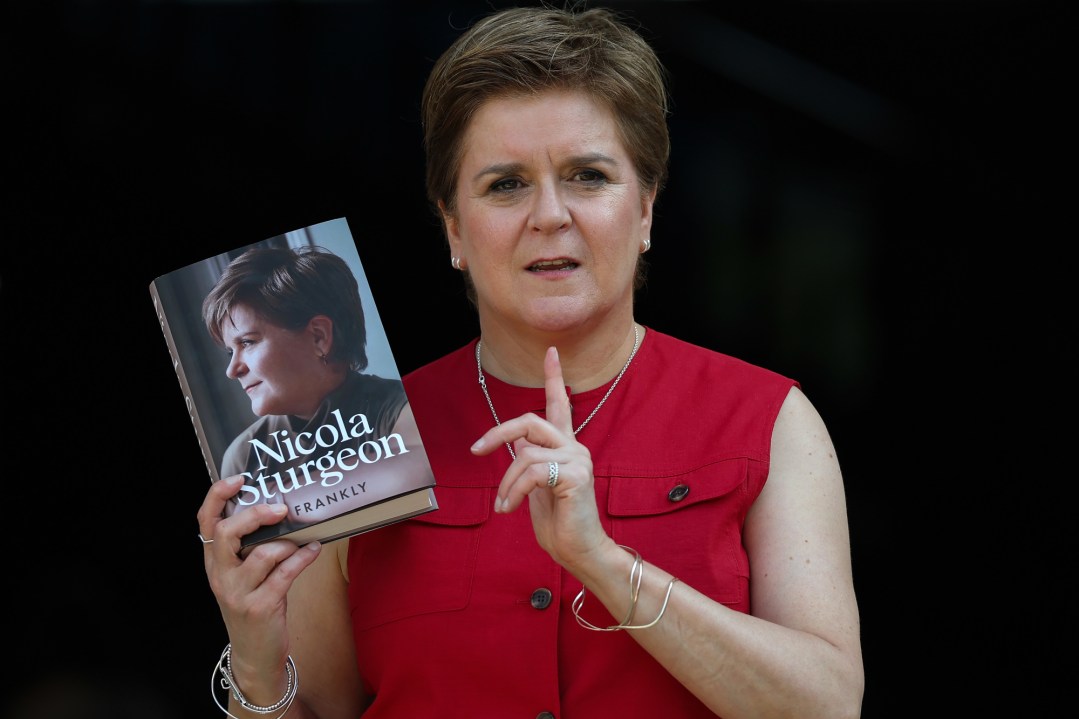

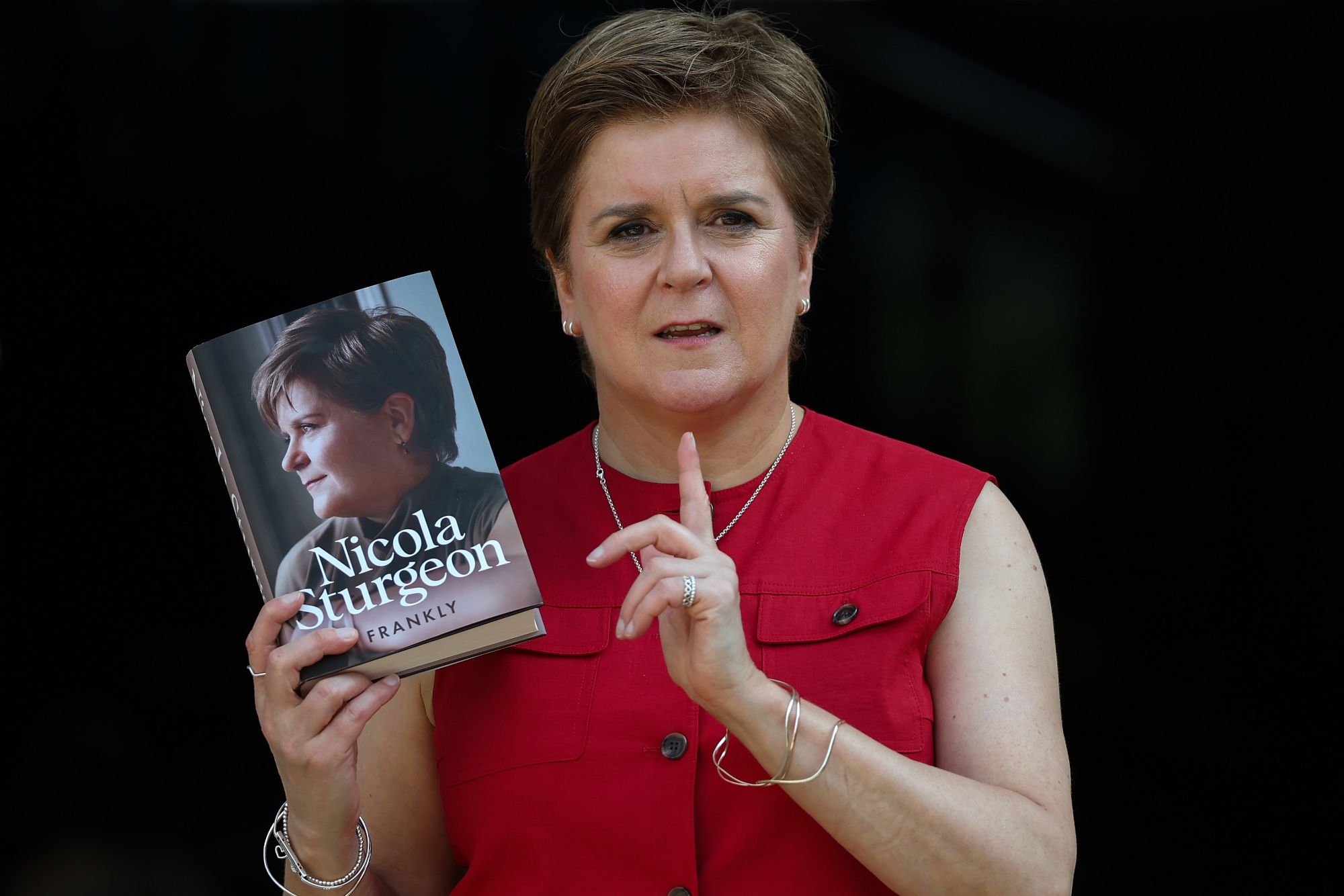

At the Edinburgh Book Festival last week she performed for a gathering of her dwindling fan base, while her legacy played out elsewhere in the festival city. There were rows raging over censorship by the Book Festival and the National Library of Scotland of the book, The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht (written by feminists, sex abuse survivors and lesbians). Kate Forbes, the woman who in a more mature Scotland might have been Nicola’s successor, was banned from a fringe venue.

After over an hour with her adoring fans, Nicola spent a very tetchy 14 minutes with Scotland’s broadcast media and print journalists having cancelled all other planned interviews with them.

In her political afterlife, as in her political life, she evades real scrutiny. For those hoping to understand better what was really going on behind the scenes during her leadership, this memoir will disappoint. It will be left to other memoirs to shed more light on what was really going on.

Comments