Artists who live long enough to enjoy a late period of working will often produce art that is radically different from the achievements of the rest of their careers. Late Titian and late Rembrandt are two such remarkable final flowerings, but Henri Matisse (1869–1954) did something even more extraordinary: he not only changed direction, he also gave up painting entirely. In the last years of his life he concentrated exclusively on making pictures, some of them vast, from cut paper. If ill health prevented him from painting, it could not stop him creating, and he reached new heights of greatness in the breathtaking beauty and daringly simplified harmonies of his cut-outs. ‘I have attained a form filtered to the essentials,’ he said.

Expectedly, colour is the key to this new work, but the real truth of it lies in light. A spiritual light, perhaps, a light that is not a physical phenomenon, but exists in its extreme purity only in the artist’s brain — and then, when he is successful in his task, emanates from the work he produces. It is difficult not to be moved by the ability of the human spirit to flower in the face of imminent extinction. Matisse faced down appalling pain during the final decade of his life by continuing to work — it was his only hope and solace. In a ‘second life’ of borrowed time, he did ample justice to his reprieve from death by embarking on a blaze of creativity which gave rise to some of the most deeply joyous pictures ever made. The Tate has now gathered together some 130 works from this late period, securing unprecedented loans that mean that many of these cut-outs are being exhibited together for the first time. The result is a show (sponsored by Bank of America Merrill Lynch) of true magnificence.

The best works achieve a tense vitality that holds in balance their two main impulses: image-making and decorative organisation. Matisse distilled the essence of his subject (taken from nature) through drawing (sometimes not even on paper, but in the air), before starting to cut prepainted sheets of paper. The process is essentially a sculptural one, closer to releasing form from a block of stone than to the additive procedure of putting paint on canvas. At his most successful — in the ‘Blue Nudes’ and ‘Memory of Oceania’ — Matisse fused the natural and the artificial in a timeless world; what John Elderfield has so cogently called ‘the physical fixing of the images of nature in the decorative context of art’.

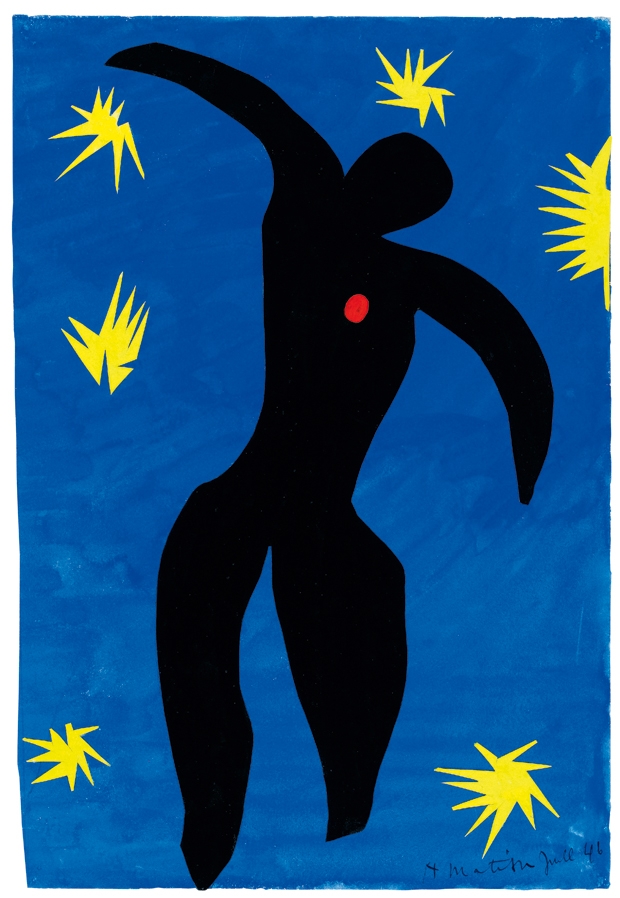

The show begins with a film clip of the aged artist at work, sliding his scissors through paper as a dressmaker effortlessly shears through fine cloth. In this first room is a fascinating coupling of a painting ‘Still-life with Shell’ with a kind of blueprint collage for it, of cut paper pinned to white canvas. These works both date from 1940 and show Matisse embarking on the process of pictorial organisation that would lead to his first cut-paper maquettes for Jazz, a book of 20 colour plates and handwritten text by the artist. Also in Room 1 is ‘The Lyre’ (1946), a beautiful small blue design, which Matisse called his first cut-out. From here we progress through a room of dancers in red, yellow and blue, to Jazz itself in Room 3, the book presented in a low lectern-like wall cabinet, with the original cut-outs hanging above it.

Matisse used embroiderer’s scissors for small shapes and tailoring shears for larger ones. As he was for much of the time bed-bound or confined to a wheelchair, assistants were entrusted with painting sheets of paper with the Linel gouache colours that he favoured because they corresponded so well to printers’ inks, allowing the images to be successfully reproduced. However, that said, the originals for Jazz make the printed book with its pochoir, or hand-stencilled, illustrations look thoroughly tame, even though it is one of the most celebrated of artists’ books. The maquettes were so obviously greater than the finished product that the cut-outs now emerged as works in their own right.

In Room 5 are two of the last paintings Matisse made and a wall of small cut-outs that sing so eloquently together that they need no individual titles (though these are available nearby) but make a new harmony of startling and sometimes intensely abstract diversity. How can this level of achievement be sustained through a further nine rooms? Inevitably, some rooms will hold the attention more than others (the decorations for the Chapel at Vence will no doubt intrigue a good many), but throughout the show the standard remains almost intimidatingly astral. Room 8, for instance, contains two of the artist’s own favourite pieces: ‘Zulma’ and ‘Creole Dancer’, both 1950, as well as the brightly layered rug design ‘Mimosa’.

Matisse experimented with rectilinearity and various framing devices, playing off the geometry of the picture plane against the organic leaf shapes or figures in movement that articulate it. He constantly breaks rules, transgressing the boundaries of any rectangle he imposes, juggling with pattern and positive/negative space. Although his cut-outs are resolutely flat, there is implied volume in his forms, part of his intention to interpret nature, not copy it. Look at the series of ‘Blue Nudes’ in Room 9, for example, one of the highpoints of the exhibition. Most people will be aware of one, or perhaps two, but few know all four in their ultramarine glory. Matisse explores variations on a favourite pose of intertwined legs and arm behind the head, deconstructing and reconfiguring it, splitting up the body into expressive paraphrases, new rhythms and structures. But the liberties he takes with anatomy are entirely accepted by the delighted eye.

There are other tremendous works to view, such as ‘Parakeet and Mermaid’ and ‘Blue Nude with Green Stockings’, both 1952, the much smaller but by no means insignificant grey-and-yellow cut-out entitled ‘The Bell’, and two magisterial works from 1953, ‘Acanthuses’ and ‘The Sheaf’. Matisse developed the art of ‘drawing with scissors’ to a high point of perfection, remarking that ‘it’s the graphic, linear equivalent of the sensation of flight’. He even thought that scissors had more feeling for line than more usual drawing materials such as pencil or charcoal; but it’s revealing that he didn’t cease to use charcoal — often in brilliant combination with the cut line, as in ‘Zulma’ or the surprisingly abstract ‘Memory of Oceania’. Colour, flight, light — the shapes are there, orchestrated by a great master, to deliver these qualities in precise quantities.

Together with the extraordinary Veronese show at the National Gallery (reviewed last week), the Matisse cut-outs currently make London one of the top art destinations in the world. The exhibition travels to the Museum of Modern Art in New York (25 October 2014 to 9 February 2015), but looks so utterly splendid in London that I recommend all to see it here. Tate Modern has never looked so good — or rather invisible: Matisse demands so much concentration, you don’t notice the setting. The curatorial team is headed by Nicholas Cullinan from the Metropolitan Museum in New York and Nicholas Serota, esteemed Tate Director. They’ve done a superb job: this is a stupendous exhibition.

Comments