In a recent interview, Hilary McGrady, the director-general of the National Trust, complains that ‘The culture wars we’re trying to grapple with are never something I supported’. I do believe her: she is not a political warrior. But what she does not acknowledge – or possibly does not understand – is that it was the wokeists within the National Trust’s staff, and the outsiders they commissioned to help them, who started the fight. There would have been no unhappiness among members if, to improve historical understanding of Trust properties, more attention had been given to the origins – good, bad or something in between – of the money which built them. We could all benefit from being better informed, for example, about how Henry VIII and friends helped themselves to the former monasteries which the Trust owns. But what was clear about the NT’s ‘interim’ report about slavery and ‘colonialism’ (a tendentious word, never explained), and the Colonial Countryside Project, which incited schoolchildren to write poems attacking former owners of Trust properties, was that these were unscholarly political projects. Some of the Trust’s senior staff also tried to take advantage of the Black Lives Matter hustle of 2020. The bosses were too scared to resist. The National Trust took, with creaking joints, the knee.

Deluged by the complaints that followed, the Trust did make some adjustments. The chairman went. Some preposterous staff tweets stopped. Some ignorant, polemical notices in Trust properties came down. Structurally, however, the Trust learnt the wrong lessons, increasing its bureaucratic power by instituting the Quick Vote system for council elections and resolutions. Its impatience with its own country houses continues. It broke its promise to rebuild Clandon Park, which burnt down on its watch, probably because it feared accusations of glorifying slavery: the Onslow family, who built Clandon, profited from West Indian plantations. In considering heritage, the test is not whether its original purposes or owners were ‘good’. Should modern Italy not care for the Colosseum because the Romans killed Christians for sport on the premises? Restore Trust, the members’ pressure group which upholds the NT’s founding purposes, is now crowdfunding a campaign to object to the Trust’s planning application to make Clandon’s ruin the Ozymandias of slavery.

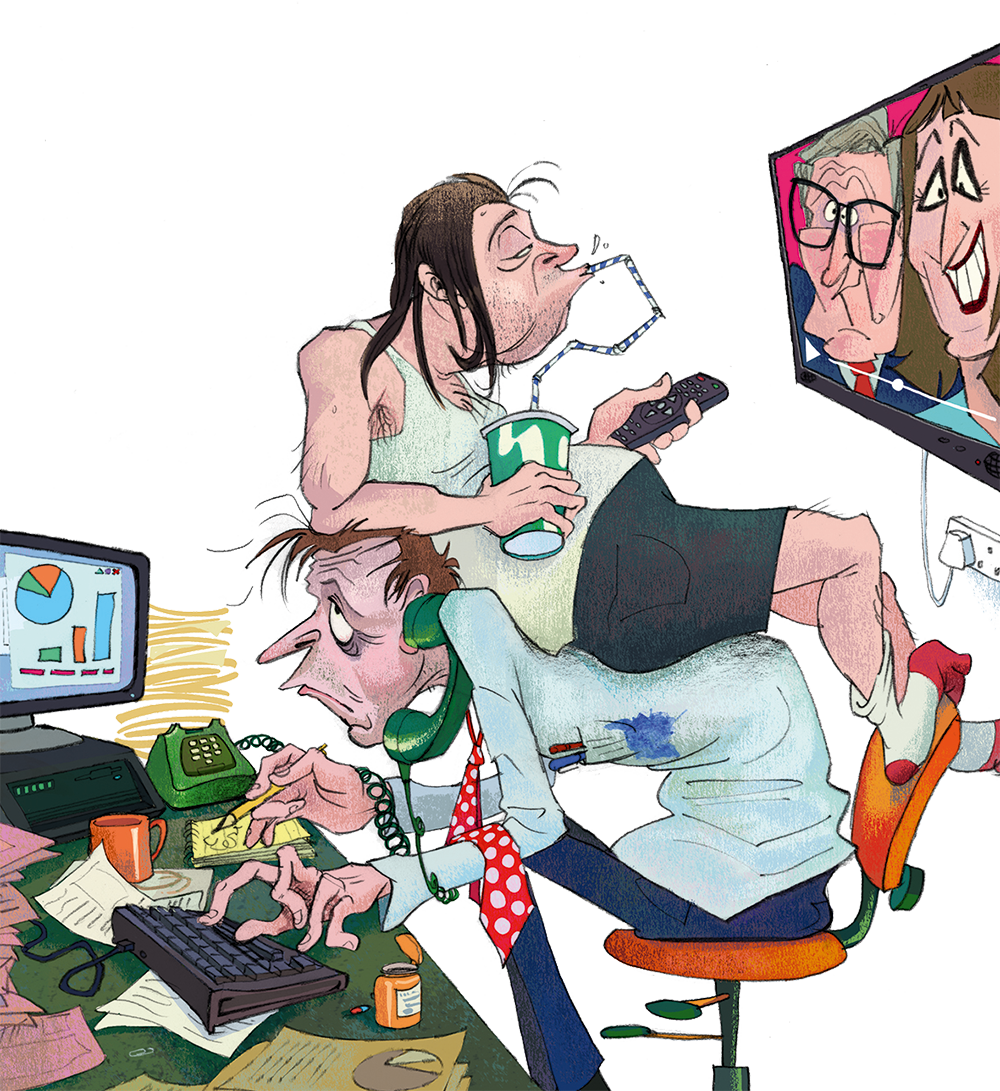

As a Trust member, I received last week a babyishly written round-robin: ‘Charles, the next chapter starts now.’ After ‘18 months of listening to 70,000 people from all walks of life’, the Trust has decided that ‘Together we can: Restore nature – not just on National Trust land, but everywhere. End unequal access to nature, beauty and history. Inspire millions more people to care and take action.’ Hilary rightly says that one of the NT’s original aims was to ‘give access’ to nature, but does not remind members that the other founding aim was to preserve ‘tenements (including buildings) of beauty and historic interest’. The ‘new chapter’ subtly moves into territory beyond the Trust’s remit. By intervening ‘not just on National Trust land, but everywhere’, it makes itself an activist agent rather than a custodian, thus neglecting the interests of members. By speaking of ‘unequal access’, the Trust is disparaging its country houses. Hilary McGrady says: ‘The majority of our places are in rural areas, but by 2030 something like 85-90 per cent of the population will live in urban areas’, so she must ‘maximise the public benefit’ by greening cities. Does she not know that by 1895 the British population was already about 80 per cent urban? It was chiefly to minister to that urban public’s need for space, nature and architectural beauty that the NT began. She says she is ‘a massive advocate of using culture to find the things we have in common’; yet, unlike the founders, she sets country against town. Contradicting itself, the Trust is also pushing for large-scale rewilding – which, almost by definition, happens outside big towns. This shows a lack of care for its tenant farmers. As our second-biggest landowner, the NT would restore our rural heritage better if it put more of its 600,000 acres into producing top-quality food.

I wish Frank Johnson, former editor of this paper, were alive to see Maria, the new film about Maria Callas. Frank wrote that almost everyone has experienced one interesting thing in life, ‘but only one’. His was as follows. In the 1950s, boys in his Shoreditch secondary school, Frank among them, were recruited to fill the crowds on stage at the Royal Opera House, being urchins in numerous productions and screaming dwarves in Das Rheingold. In 1957, Frank and one other boy were called in for Norma to be the heroine’s two children whom she decides to stab to death, but then relents, ‘opting instead for a duet with a mezzo-soprano’. Callas was Norma. Frank forgot most of the evening but ‘I could not forget that when Callas bore down on us with knife, her nostrils flared; that when, dropping the knife, she repentantly clasped us to her bosom, her perfume smelt like that of an aunt who was always kissing me; and that… there penetrated, into my left eye, the top of the diva’s right breast, which partnership remained throughout the subsequent duet’. In that eye, Frank felt ‘the most distinct pain as that voice of myth and legend rose and fell. In the other eye, all I could see was the exit sign at the far corner of the gallery. At the second performance, I ducked and secured a central portion of the diva’s bosom’. ‘There are few men,’ Frank concluded, ‘who can truthfully say that their eye made contact with the right nipple of Maria Callas.’ I bet this scene is not rendered by Angelina Jolie.

Our new editor has kindly renewed the traditional permission to advertise here the AGM of the Rectory Society, which I chair. It will take place in Chelsea Old Church, at 6 for 6.30 on Tuesday 11 February. I shall interview our guest of honour, A.N. Wilson, our greatest living man of letters. For tickets, please contact alisoneverington@gmail.com.

Comments