Cast your mind back to April 2023, when Ding Liren from China became the world champion, defeating Ian Nepomniachtchi in Astana. After 14 seesaw games, Ding triumphed in a rapid tiebreak, in which his move 46…Rg6! from the final game was a memorable piece of brinkmanship, living dangerously and pushing for the win.

December 2024 saw the conclusion of Ding’s title defence in Singapore against his brilliant 18-year-old challenger Gukesh Dommaraju from India. Alas, the majestic courage which Ding showed in Astana has seemed to desert his game ever since, to the point where Gukesh was considered a heavy pre-match favourite.

To the delight of this spectator, Ding brought character and resilience to his title defence, and the match remained tied after 13 games. The champion showed flashes of his imperturbable best, and won a couple of strategically profound games. But more often, he allowed his advantages to fizzle out into draws, seeming not to believe in his opportunities. Gukesh, by contrast, was the lionheart of this match, relishing any chance to prolong the tension.

Viewed narrowly, Gukesh’s victory in the 14th and final game was fortuitous, but in the big picture it was thoroughly deserved. In the middlegame, Ding’s evident desire to steer the game towards a draw entailed a series of small concessions. His chances for a draw remained high – perhaps 90 per cent, but the other 10 per cent of the chances were all on Gukesh’s side. Sure enough, he got the break he was looking for, when Ding made the fateful blunder below.

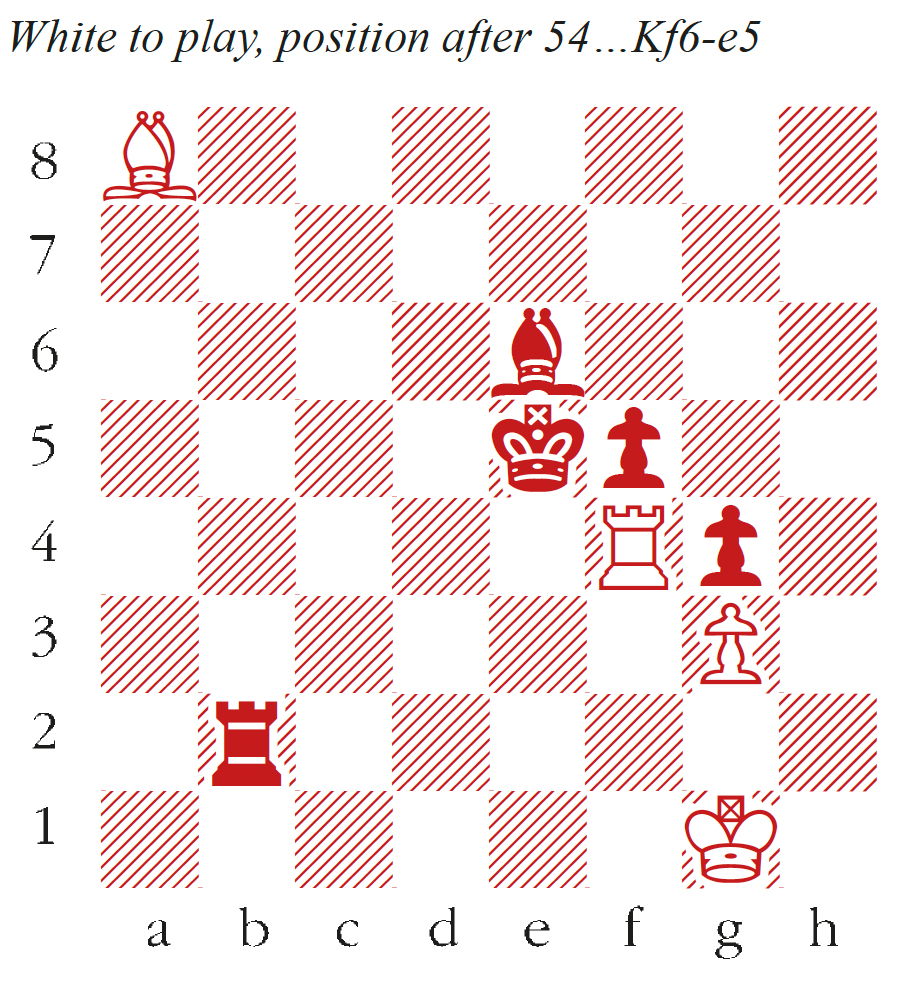

Ding Liren-Gukesh Dommaraju

Fide World Championship, Game 14, Singapore 2024

Both players would have expected Ding to achieve a draw with accurate play, but it is no formality. The main winning attempt for Black is to bounce his bishop around to e4. White would be reluctant to cede the diagonal, but the alternative – trading the bishops on e4 – creates a dangerous passed e-pawn. For example, a plausible continuation such as 55 Rf1 Bb3 56 Bc6 Bc2 57 Ra1 Be4 is already winning for Black. A better defence would be 55 Ra4, preparing lateral checks. But Ding probably felt uncomfortable with his king pinned to the back rank, so: 55 Rf2?? A losing blunder. In itself, the exchange of rooks is benign, but the infelicitous position of Ding’s bishop on a8 allows Gukesh to force the bishops off as well, reaching a winning king and pawn endgame. Rxf2 56 Kxf2 Bd5 57 Bxd5 Kxd5 58 Ke3 Ke5 White resigns

The players would both have considered the win as trivial from here on, but a couple of finesses deserve mention. 59 Ke2 Ke4! or 59 Kf2 Kd4! are hopeless, but 59 Kd3 f4 60 Ke2 sets Black a trap. Should Black play 60…fxg3, the position is already drawn in spite of the two extra pawns, e.g. 61 Kf1 Ke4 62 Kg2 Kf4 63 Kg1 Kf3 64 Kf1 g2+ 65 Kg1 when either 65…Kg3 or 65…g3 leads to a draw by stalemate. Instead of 60…fxg3, the winning move is 60…f3+. But after 61 Ke3, there is one further surprise: the only winning method involves sooner or later sacrificing the star pawn on f3, e.g. 61…f2 62 Kxf2 Kd4 63 Ke2 Ke4 64 Kf2 Kd3, and Black wins by ‘outflanking’, sidling towards the g3-pawn. After Black captures that pawn, the favourable position of his king ensures that the endgame is a trivial win.

Comments