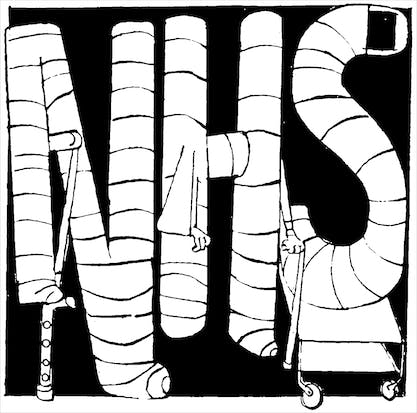

The NHS is one year older, yet none the wiser. Having spiralled into perpetual crisis years ago, no one can pretend the gargantuan system is looking great for its age. Its fragile condition has all of us worried – not least because of the millions of lives that are forced to depend on our monopoly health service. The NHS’s woes are thought by some to be the result of some evil right-wing push towards privatisation – and by no means a reason to hold back oodles of praise for the healthcare system. If anything, the health service’s troubles have served as a call-to-arms to defend the status quo.

But despite the jabs and digs and efforts to politicise today’s landmark, most of the tweets on the #NHSBirthday feed are simply glowing, to the point that you could sub in ‘Mother Theresa’ for ‘NHS’ with ease. While every day seems to be a pro-NHS day for some, today the love is starkly on show. But these heaps of praise directly contrast what we know about the NHS.

Far from being the ‘envy of the world’, no country has tried to emulate the NHS like-for-like. That’s not to say the principle of universal healthcare hasn’t spread – almost every country in the developed world offers 100 per cent access to care, regardless of one’s ability to pay. The main outlier is, of course, the United States, which makes the rabidly pro-NHS lobby’s comparisons to the States so poor. Using the only system you can find that doesn’t deem healthcare as a right for all citizens is plain fear-mongering, and bares no reflection on how your own system stands up to the rest of the competition.

It’s likely the ‘Yanks or Brits’ tactic is used so frequently because the UK’s neighbours put the NHS to shame. As my colleague Dr Kirstian Niemietz has pointed out, international comparisons tend to rank the NHS in the bottom third when it comes to patient outcomes – on par with the Czech Republic and Slovenia. Its poor data could never be confused with Germany, the Netherlands or Belgium; these countries’ systems save thousands more lives each year, especially when it comes to serious conditions such as cancer.

The OECD, the World Health Organisation, and European Health Consumer Index all tell the same story: long waiting times, sub-par outcomes and little patient empowerment. Indeed, it is the social health insurance models – in which a government’s role is to fund and regulate healthcare, and it is the private sector’s role to provide the actual services – that secure top ranks for patient outcomes.

The only exception in the general consensus about the NHS is the Commonwealth Fund study, which in 2014 ranked the UK as having the best healthcare system. Always rolled out in an attempt to sweep the NHS’s problems under the rug, this study focuses on inputs into healthcare systems, not outputs. Inputs are important, and are a legitimate way to measure a healthcare system. But questions like ‘Physicians reporting it easy to print out a list of patients due or overdue for tests or preventative care’ are not comparable to cancer survival rates. When the Commonwealth Fund study asks about patient outcomes (‘Hospitalised patients went to ER or rehospitalised for complication after discharge’) the NHS plummets from the top of the chart to tenth (out of eleven). The Guardian’s radiant review of the study managed to sum it up perfectly, when they wrote, without any irony, that ‘the only serious black mark against the NHS was its poor record on keeping people alive’. How’s that for the greeting inside the birthday card?

The founding of the NHS in 1948 symbolised the right to access quality healthcare, rich or poor, without consequence. For that, the NHS deserves credit. But today’s celebrations blatantly ignore the trends of more successful countries and the failures of the UK’s system that was designed for demographics from nearly 70 years ago. Unless serious alternatives are considered to keep healthcare afloat, the situation is bound to get worse.

Blowing out the birthday candles for the NHS takes on a much more sombre, menacing feeling when the state of our National Health Service is fully realised.

Kate Andrews is news editor at the Institute of Economic Affairs

Comments