The translator’s preface to the third volume of The Aesthetics of Resistance informs us that ‘Several deadlines came and went on the way to this translation’. That is quite the understatement. The German edition of Peter Weiss’s 1,000-page historical novel appeared in 1975. A full English translation has been in the offing for more than 20 years. In the meantime, Weiss has won just about every literary accolade Germany has to offer, and his play Marat/Sade has become known as the theatrical ‘starting gun’ of the 1960s. Whatever the translator Joel Scott has in store for us, it had better be worth the wait.

Weiss was moved to write his magnum opus by the same question that animated his great model Bertolt Brecht, who actually appears as a minor character in Volume II: how to make art that is simultaneously avant-garde and committed. Or, as another character puts it: how to ‘match up the intensity of revolutionary artistic and political actions… the irony of the one with the seriousness, the sense of responsibility, of the other’.

Weiss’s solution was to write a vast, meandering monologue, largely without paragraph breaks, of the kind that will be familiar to readers of later Germanic writers such as Thomas Bernhard and W. G. Sebald. Interlocutors are never quite afforded voices of their own. Instead, their wordy disquisitions on art and history remain imprisoned in free indirect constructions: ‘Such a structure, borrowing, said Coppi, from the ideas of Saint-Just, Babeuf, Proudhon, can only lead to anarchism…’

This endless, airless prose works through accretion. Nothing much happens for page after page. Conversations about dialectical materialism slide into long descriptions of the Pergamon altar or Géricault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa’ and back again. Yet somehow, gradually, we start to detect the lineaments of, if not quite a character, then a particular sensibility and position in history that reveal the protagonist as a thinly fictionalised version of Weiss himself.

Volume I begins with the young narrator’s education among members of the resistance in Nazi Berlin – plus a few proletarian embellishments that early reviewers dismissed as products of a guilty conscience – and ends with him running off to Spain to join the International Brigades. Volume II sees him move to Sweden, where he continues to wax Leninist in the relative safety of a tolerant social democracy.

The novel makes modernist tomes like Ulysses and The Unnamable look positively inviting

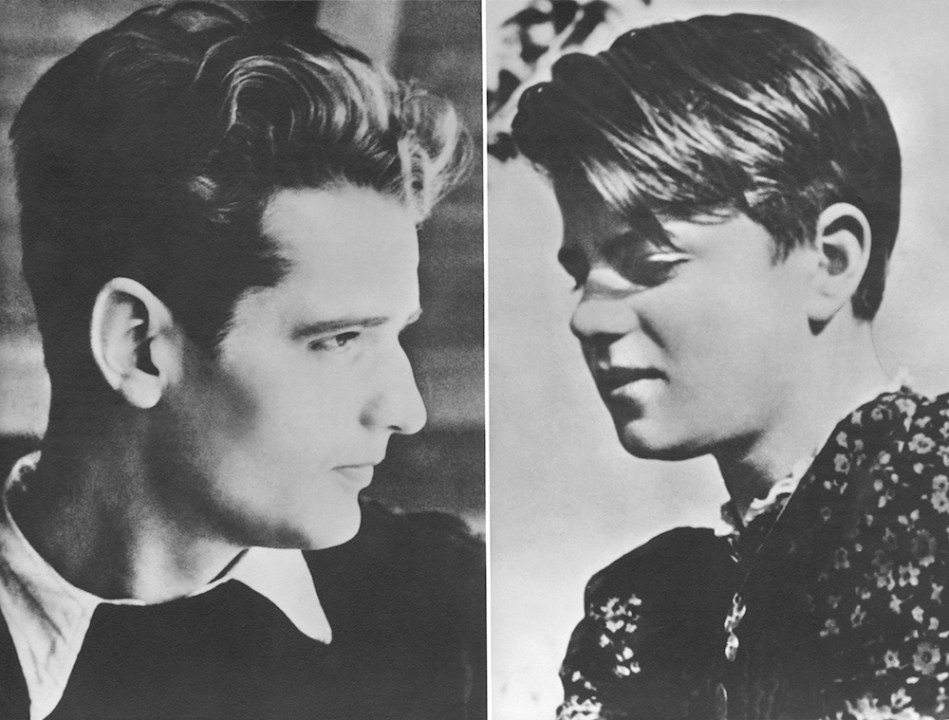

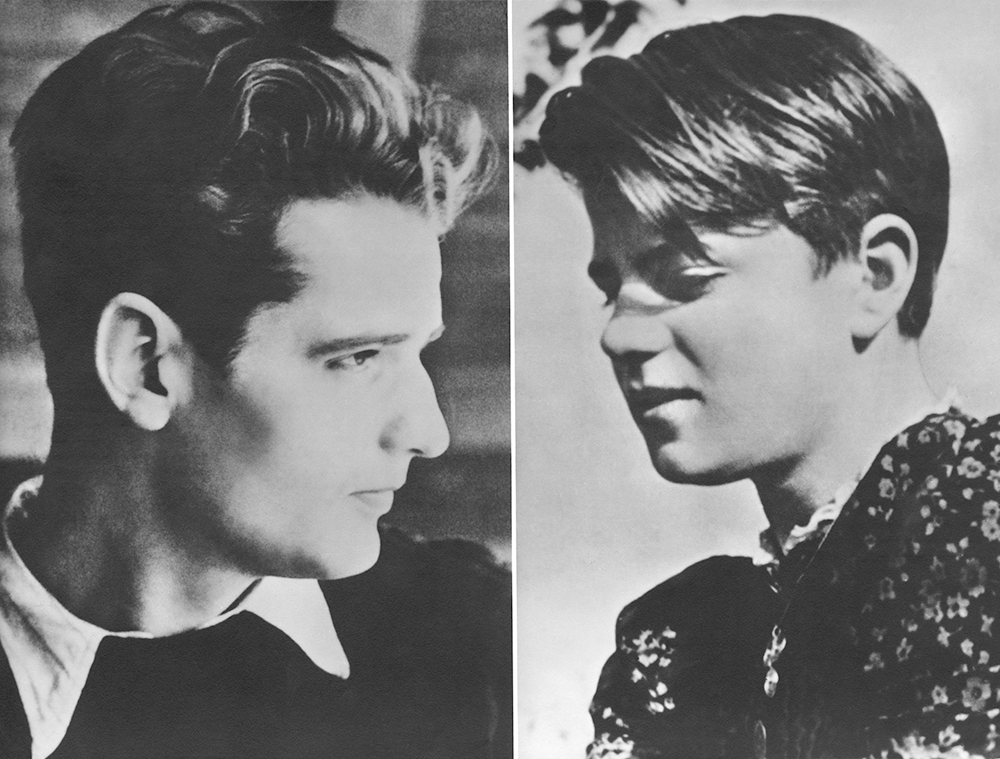

For readers who have managed to make it this far, the third and final volume strikes a slightly different note. There are fewer ekphrastic interludes, and the meandering conversations about dialectical materialism, though still very much present, are less callow and more ironic. We are in Berlin again. The members of the Red Orchestra resistance group, with whom the narrator had associated in his youth, are being rounded up and sent to Plötzensee prison, where they are interrogated, tortured and executed. Even formerly longwinded comrades slip into bitter aphorism. Charlotte Bischoff, the beautifully rendered communist resistance fighter to whose views much of this final volume is devoted, replies deflatingly to the narrator’s latest sweeping thesis about the relationship between violence and culture: ‘We lost our hold on culture because we failed at politics.’

The Aesthetics of Resistance is not the kind of book one reads without strenuous mental preparation. Its length, its allusiveness and the strangely hectoring quality of its characters’ orations may be justified by its subject matter – but they make other difficult modernist tomes such as Ulysses and The Unnamable look positively inviting. Nor should the comparison with Bernhard fool anyone: this may well be the least funny novel ever written. But who reads a novel like The Aesthetics of Resistance to be entertained? This is a book that aims to elicit awe rather than enjoyment; it wants to have evenings lost to it, discussion groups consecrated to it and to leave a permanent mark on Europe’s high culture – which, for all his ambivalences, Weiss still seems to think might be the only thing that can save us.

Comments