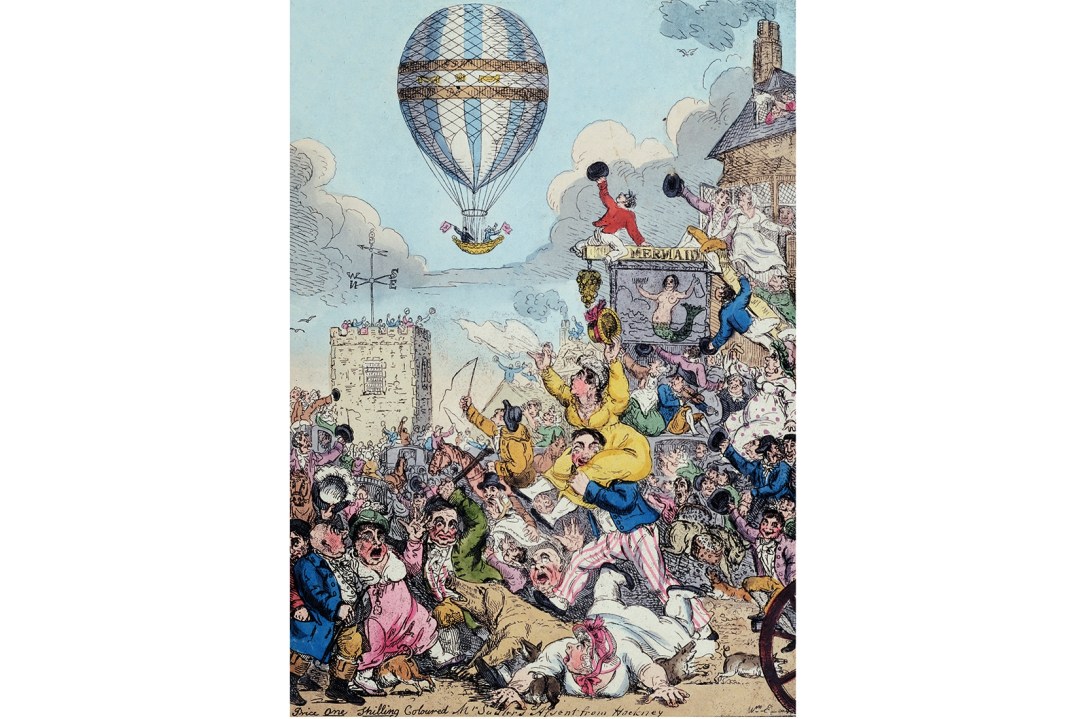

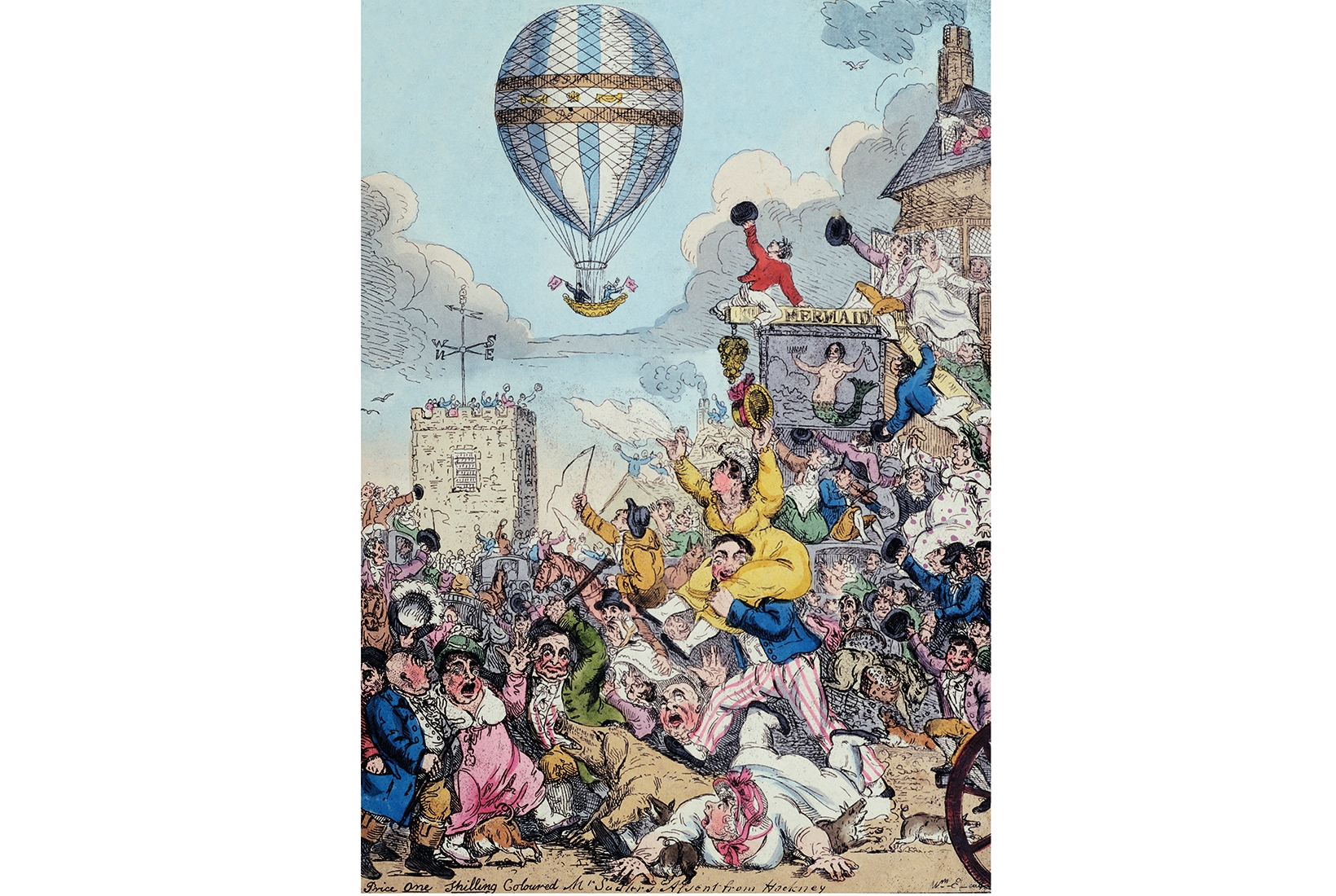

Edinburgh, 3 November 1815. The university courtyard is buzzing. A band is playing. Surrounding streets are filled with thousands of excited spectators, many waiting since 10 a.m. From the Castle, from windows and rooftops, from Calton Hill, Holyrood Park and Salisbury Crags, all strain to get a glimpse. Then finally at 3 p.m., above the university, a large balloon suddenly emerges, climbing wondrously into the crisp November sky.

Orchestrating this aeronautical display was pioneer English balloonist James Sadler. His balloon rose majestically as the westerly wind took it towards the sea. Sadler continued waving his flags as long as he could be seen, and the crowds applauded and gasped.

Having forgotten his map, and with visibility worsening, Sadler cut short his planned flight, landing after 20 minutes by the Forth. An animated crowd followed him, causing such a crush that balloon and car were totally destroyed, bits carried off as souvenirs. Sadler, exhausted, was borne shoulder-high in triumph into Portobello.

Despite capturing the popular imagination, Sadler’s balloon was a fringe event. Edinburgh had long been in a state of fevered excitement, with people flocking into the city from far and wide in anticipation of the very first Edinburgh Musical Festival.

Women fainted with ‘fright and pressure’; irate altercations occurred with the police

Three days before Sadler’s ascent, on Tuesday 31 October, the inaugural concert had opened in a packed old Parliament House, launching the greatest musical extravaganza that Scotland had ever seen. Hugely popular, the six concerts almost sold out — 9,011 tickets overall, 2,141 for Handel’s Messiah alone.

Thanks to Covid-19, Edinburgh this month is empty, for the first time in 73 years. Edinburgh International Festival was conceived in 1945 to ‘provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit’ and help Britain and Europe recover from the war. The first Edinburgh Musical Festival also emerged from challenging times at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, opening just four months after the Battle of Waterloo.

There are other resonances: the explicit priority of the 1815 festival was to raise as much money as possible for charitable purposes — an impressive total of £1,500 (approximately £140,000 today) over the five days. Leading the list of 17 beneficiaries were Edinburgh’s Royal Infirmary and the new Lunatic Asylum, each receiving £400. Even 205 years ago the authorities wished to support physical and mental health, as well as relieve poverty.

‘Improvement’ was the watchword, but not just financially. For one commentator, the festival was designed ‘to improve the moral habits and feelings of the people. Most of our vices arise from the abuse of our leisure hours; and no means can be more effectual in stopping their progress than those which provide an innocent recreation to the mind, without corrupting it. Of all the amusements of this kind, we know of none more fascinating than music’.

Interestingly, Edinburgh had come late to the festival phenomenon. Eighteenth-century Handelmania had inspired northern English towns to mount their own festivals — in Leeds as early as 1767. Edinburgh’s cultural leaders visited these festivals and now wanted one of their own. In December 1814 the great and good met in the Lord Provost’s office to propose an ‘Edinburgh Musical Festival’, the following year, with six musical performances, on this English model. There were to be three oratorios or selections of sacred music in the morning, and three ‘Miscellaneous Concerts’ in the evening.

A 62-man board of patrons and directors was formed, led by the Duke of Buccleuch. The striking lack of professional musicians among these board members was unsurprising, however, given the Kirk’s sustained suppression of music following the Reformation. Edinburgh’s musical scene was therefore dominated by foreign musicians, primarily Italian, with a few Germans and Englishmen. Few local musicians were of the calibre required. The festival’s orchestra leader was Lithuanian virtuoso Felix Yaniewicz, alongside the Paganini of the double bass, Domenico Dragonetti, Robert Lindley, cello, and Mr Holmes, bassoon, both English.

Londoner Charles Ashley, a long-time organiser of Handel-based festivals, was contracted as festival conductor to bring the best vocal and instrumental performers from London. The orchestra was substantial (unlike many Handel performances today) with 24 violins, seven violas, six cellos and five double basses, alongside two oboes, three flutes, two clarinets and two bassoons, a brass section of two each of trumpets, horns and trombones, and one ‘drum’. Established opera stars of the day, including supreme tenor John Braham, joined a chorus of 58 singers. The unprecedented sound produced by 120 performers astounded Edinburgh audiences.

The demanding five-day programme focused on oratorios by Handel and Haydn, with symphonies by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Highlights were Haydn’s Creation in the opening concert and Handel’s Messiah.

There being no purpose-built hall that could accommodate festival audiences, morning concerts were held in the old Parliament House, home of the Scottish justiciary since the abolition of the Scottish Parliament in 1707, where a temporary balcony and the Covent Garden organ, shipped up via Leith, had to be installed for the duration. Evening concerts were held in Corri’s Rooms, a large multipurpose building, long since disappeared, at the top of Leith Walk, managed by one of Edinburgh’s prominent musical Italians.

There were problems, too, of course. Some concerts were massively oversubscribed. More than 600 were turned away from the Messiah alone. Newspapers reported that women fainted with ‘fright and pressure’. Frustrations boiled over; irate altercations occurred with the police. Angry letters appeared in the press. And ‘so great was the competition for admission, that the different parties found it necessary to come out of their vehicles; and ladies in full dress were forced to stand waiting in the dirty streets until the doors were opened, after which the crush was excessive’.

Unsurprisingly, directors faced unfounded allegations of reserving seats for their families and friends.

Audiences, however, loved it. Tellingly, the Friday concert had to be brought forward by an hour to enable the crowds to witness Sadler’s ascent. A contemporary reported that by the ‘liberality and good taste of the good people of Scotland, this scheme for the display of music on a greater scale than was ever before attempted in this country, has met with unparalleled success’. And in Sadler we can say we had the original Fringe first.

The 1815 festival firmly, if belatedly, placed music at the heart of Edinburgh’s Golden Age. Two further Festivals took place, in 1819 and 1824 respectively, and unsuccessfully in 1840 and 1843, but it would take another century and two world wars finally to embed the festival phenomenon in the hearts and minds of Scotland’s artists, politicians and wider public.

The Edinburgh International Festival and Festival Fringe is online this year at eif.co.uk and edfringe.com.

Comments