At the end of last century, when there were grounds for optimism about Russia’s future, an increasingly popular word expressed this: stabilnost – stability. Russians would roll it round their mouths as a Texan would use ‘goddam’, or an English after-dinner drinker of an earlier vintage might evoke his enjoyment of the beverage by letting the word ‘port’ linger across his palate. I do not suppose that there is much talk of stabilnost in Moscow these days, and we could do with some of it here. Still, there are ways of banishing dull care, if only for a few hours, and drinking fine claret is one of them.

The other evening, I was at a tasting of Branaire-Ducru and my first conclusion was that I had not drunk it nearly often enough. It is a St Julien. Saint Julien himself was a curious cove. An enthusiastic deer hunter, he was once confronted by a hart which told him that if he continued to hunt, a terrible fate awaited him. He did, and the hart’s predictions came true. He repented, received divine forgiveness and then opened an inn, becoming the patron saint of travellers: from Greta Thunberg to Eastcheap.

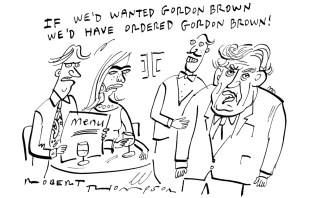

I am not convinced the 1970s always drink up to their reputation; this one did

The area named after him is the smallest of the great four Medoc communes, bordered by Pauillac and Margaux. I once wrote that you drink a Pauillac but undress a Margaux, so St Julien is betwixt and between. It does not possess a first growth, though Léoville Las Cases and Ducru-Beaucaillou are super seconds and Léoville Barton not far behind. Branaire-Ducru was awarded fourth-growth status in the 1855 classification but has certainly earned promotion.

It can also lay claim to stabilnost. It emerged from the break-up of the great Beychevelle estate in the late 17th century. The Chateau itself is 200 years old. I visited 20 years ago, and remember the house being handsome rather than beautiful: the type rich squires would have commissioned as France returned to stability after Revolution and Bonapartism.

The vineyard also gave the impression of being a family property with deep roots in a long past. Not so: the Maroteaux family only bought it in the late 1980s. But without over-indulging in mysticism – or should that be sentimentality? – when an estate and the right owners come together, the result is not just a commercial transaction. There is a meeting of souls.

Francois-Xavier Maroteaux, the current owner, is a man in the grip of a vocation. Like all the finest wine-makers, he strives to fuse terroir and technique, constantly studying the most up-to-date methods in order to enhance the laurels earned by the faithful departed. We are in the presence of a Burkean communion: the dead, the living and the yet-unborn.

His wines were all excellent, but I thought some of them needed more time, even when served en magnum. That was true of the 2000, the 2005 and the 2010. All would have benefited from another five years in the cellar. That said, friends whose judgment I trust regularly complain of my necrophiliac tendencies when it comes to claret, and all of those bottles were jolly good drinking. A Frenchman would have seen no reason to hesitate before opening them. I just think that they could have been even better.

But the 2009 was everything it should have been, as was a 2010 Duluc de Branaire-Ducru, the second wine. The surprise of the evening was a 1970: pre-Maroteaux. After 50 years, it was still fresh and fruity. Admittedly the 1970s have a great reputation, but I am not convinced that they always drink up to it. This one did. Perhaps because of the fourth-growth status, Branaire-Ducru does not enjoy the reputation to which it should be entitled. That has one advantage for hard-pressed oenophiles. It is a good value.

Comments