As I’ve occasionally come to think is the case with The Spectator, this book is perhaps best begun at the back. Otherwise it might be taken for niche history – applied historical moral philosophy, say, or an aspect of ‘the people’s war’ usually overshadowed by the manifest imperative to defeat the unparalleled evil of Nazism.

That evil, concludes Tobias Kelly, professor of political and legal anthropology at Edinburgh, has indeed ‘become the frame through which we seem to assess all evils’; but ‘the spectre of appeasement has also reared its head too often’. As a result, ‘we have been quick to get carried away with the virtue of war when confronted with wrongdoing and too ready to believe that a just measure of violence can solve the world’s problems’.

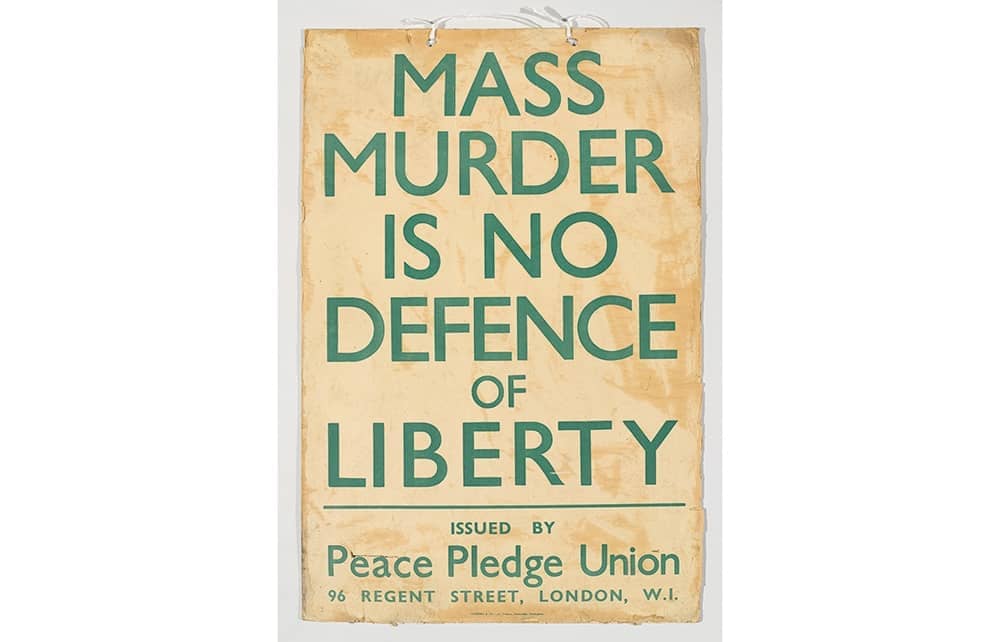

We may be too ready to believe that a just measure of violence can generally solve the world’s problems

Kelly maintains that although the conscientious objectors of the second world war could sometimes be blinkered and self-important, and that we might be tempted to think of them as unable to come to terms with a cynical and brutal world, ‘they could also become passionate and committed to the ideal that violence is not inevitable’. At their best, ‘they confronted the world head on, taking it as it was, but not resigned to its fate, imagining in both hope and sorrow that things could be otherwise’.

But was their best really good enough? I recall a long conversation about his wartime pacifism with my Anglican confessor, Father Anthony Perry SSM, in the days before I crossed the Tiber. (Once on the far bank, pacifism seemed less of an issue: as Kelly reminds us, the Pope has his Swiss Guard.) As a 19-year-old, Perry had served with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in China, no cushy number. The Quaker FAU features large in Kelly’s book. One day one of its drivers correctly refused to stop to give a Chinese soldier a lift: it would have been a breach of the Geneva Conventions. The soldier began throwing stones at the truck. The driver stopped and thumped him. Having done so, he concluded that he was not in truth a pacifist, and left the FAU to enlist in the army. This I think is an extreme case of scruple. Why should a pacifist be any more perfect than a man carrying a rifle? Confession, absolution, penance – and then carry on. But as Kelly writes, conscience is always very personal (and pity the poor tribunals whose job it was to examine it).

There is of course a difference between absolute pacifism and objection to a particular war on the grounds that the jus ad bellum have not been met. I know an officer who refused promotion to lieutenant-general for an appointment in Iraq; he no longer believed in the war and left the army. There were, says Kelly, 60,000 British ‘conchies’ in the second world war. I shouldn’t have been surprised, for I learned only recently that my own maths master, a Quaker, had gone to prison for his beliefs.

Kelly chooses to examine these battles of conscience by following the experience of five very different but ordinary (perhaps I should say ‘illustrative’) people, by no means all intellectuals or religiously driven, although to expand on their particular cases he cites hundreds more, including familiar names such as Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, Michael Tippett and W.H. Auden. Britten visited Belsen and other liberated camps in 1945 with Yehudi Menuhin, giving recitals; but, according to his biographer Paul Kildea, he saw the Holocaust not as a unique event but as ‘part of the wider logic of war and violence’. This I take to mean ‘no war, no Holocaust’. But how could Britten be sure of the consequences of inaction? Yes, if there had been no war in 1914 there would possibly, even probably, have been no war in 1939. But a principle of moral philosophy is that you can only proceed from where you find yourself, and 1939 was a very different place to 1914.

As Kelly points out, when Britten – who told Pears that what he’d seen in Germany shaped everything he’d written since – composed his War Requiem (1962), he turned to the first world war, not the second. That may have been because of Wilfred Owen’s compelling poetry. But whereas the slaughter of the first world war provokes almost universal horror in its ‘senselessness’, even ‘futility’, that of the second is always mitigated by the nobility of the cause: the extirpation of unmitigated evil. (Eisenhower’s wartime memoirs are not called Crusade in Europe for nothing.) This moral legacy of the Western Front is evident in much of the debate that Kelly examines. It was certainly so with Vera Brittain, who also features large. My mother, who met her through Winifred Holtby in the early 1930s, used to shake her head and say: ‘She simply couldn’t see it was a completely different war.’

Kelly’s charge that we may be too ready to believe that a just measure of violence can generally solve the world’s problems – ‘Give War a Chance’, the protest song of the neo-cons – is clearly one to think on. It is said that field marshal Lord Guthrie, with Sir Michael Quinlan, wrote his 2007 monograph Just War in order to rein in Tony Blair. I’ve no idea what Blair said in his thank you letter. Perhaps just: ‘It’s complicated, Charles.’ Battles of Conscience is a moving tribute to moral courage, and a scholarly memorial of more innocent times.

Comments