No one likes a pedant. But over the past few millennia, people have shunned pedants, bores and know-it-alls for a wide range of different, often conflicting, reasons. They have been accused of obscuring the path to true philosophical knowledge and of putting learning on too high a pedestal; they’ve been regarded as unfit to be democratic leaders; too unskilled in the aristocratic virtues; too keen to rise above their natural class; and as stubborn impediments to a true comprehension of the divine.

At times they’ve been deemed too unmanly and too feeble; at others, far too boorish, charmless, unable to think for themselves and probably horrible at parties. Arnoud S.Q. Visser, a professor at Utrecht University, provides a history of the pedant, tracing a lineage from the Sophists through to representations of academics in contemporary American cinema. (The Nutty Professor gets a good showing, both the 1963 original and the Eddie Murphy remake.)

As Visser writes, the word pedante emerged in 15th-century Italian. Though its etymology is uncertain (perhaps from the Latin pes or the Greek pais), it referred to a ‘professional teacher of Latin grammar, literature and rhetoric’ and before long it had taken on pejorative implications (‘connoting the defects and vices of teachers more broadly’).

But pedantry, of course, existed long before the word did, and so Visser’s narrative begins in Ancient Greece, with the tension between the philosophers and the Sophists. The latter were teachers of oratory and persuasion, who earned fame (and sometimes considerable wealth) as intellectual celebrities, propounding the virtues of rhetorical and epistemic flexibility. They introduced powerful, usable skills in argumentation to ambitious citizens seeking influence in a society transitioning from oligarchy to direct democracy. Plato, for one, loathed them. Too interested in framing debate as a form of competition and in winning arguments, he thought – and far too uninterested in discovering the truth.

From there, Visser takes the reader on a whistlestop tour through the philosophers of Rome, the scholars of medieval Europe, the humanists of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, America’s Founding Fathers and on to 20th-century Hollywood. In the early years of the United States, Visser points out, certain kinds of learning were considered suspicious. Benjamin Franklin ‘viewed the study of the classics as a fashion statement, comparable to the use of hats’. Trendy perhaps, but having little utility, especially since the key texts were by then available in English translation. Thomas Jefferson ‘believed that overly theoretical learning hampered sound judgment’. Ironically, Jefferson’s own reputation as an intellectual gave political ammunition to his Federalist opponents in the election of 1796.

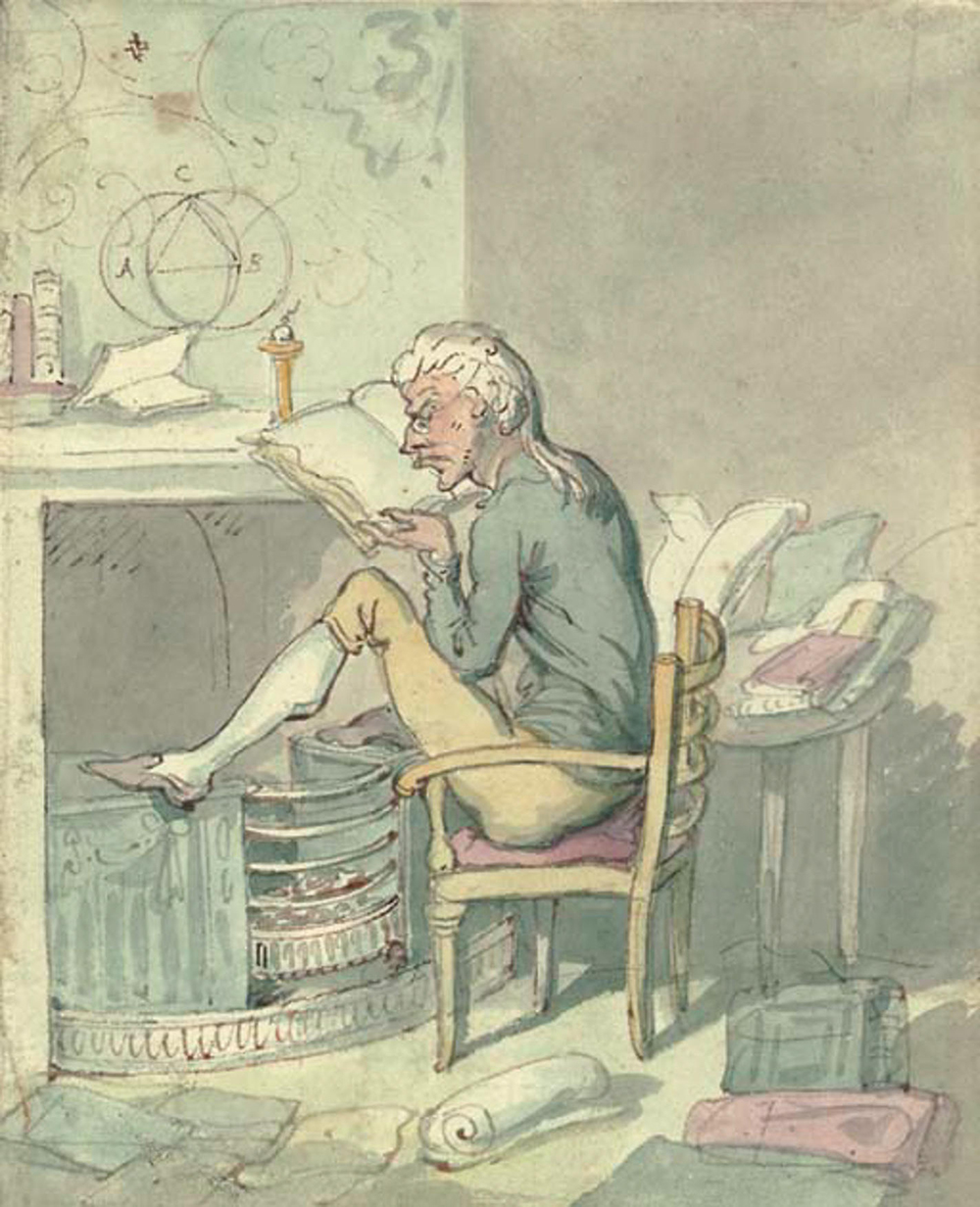

The pompous, foolish pedant became a stock character in16th-century Italian comedy

A recurring theme is the joy that dramatists have taken in mocking these figures. Visser cites The Clouds by Aristophanes, in which Socrates is (curiously) cast as the leader of an immoral sort of sophistic intellectualism. In the 16th century, the pedant, pompous, foolish and prone to the needless use of Latin, became a stock character in Italian comedy before spreading more widely across European theatre. And eventually this cultural legacy found expression in the movies (along with the pedant’s distant cinematic cousin, the ‘mad scientist’). Visser splits the period into two temporal chunks: ‘Pedantic Fools (1910-1960)’ and ‘Vulnerable Pedants (1960s onwards)’. Roughly, that is, a change from professors you’re meant to hate to those you’re meant to pity.

Across its seven chapters, the focus of Visser’s book is prone to drifting, and the subject occasionally becomes unwieldy. At times, we are reading about a specific figure – the pedant in the narrow sense, dry, disputatious and pretentious. At others, the aperture widens to cover intellectuals and learning more broadly, with general reflections on their reception in society.

But one suspects the subject is intentionally broad. What comes through clearly is the idea that whoever counts as a ‘pedant’ is a decision for the name-caller. It is less a stable, provable category and more a term of abuse – a way for one group to claim the moral and intellectual high ground over another, and thus to pursue social advantage. The Greek philosophers made plain their disdain for the Sophists; Roman philosophers despised the grammarians; the theatre-going nobility of the 16th century had strong incentives to knock down the upstart intellectuals who posited a new ‘nobility of the mind’ and threatened to disrupt the traditional order; and the American revivalist preachers of the 19th century had good reason, in an ‘emerging consumer economy’, to promote spectacle over tedious, elitist book learning.

The accusation of pedantry is a powerful tool to delegitimise an opponent while bolstering one’s place, and one’s point of view, in a social hierarchy. It may be humiliating to be accused of being wrong, but how much worse, and more debilitating, to be called a bore.

Comments