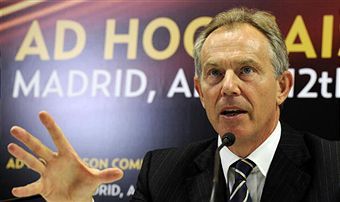

Fleet Street resounds to just one gag today: every ash cloud has its silver lining. Tony

Blair is marooned in the Middle East and won’t be plugging his memoirs at this week’s London Book Fair. I wonder if he’ll adopt a few Semitic shrugs to accompany the gauche Cary

Grant accent. Still, we must wait longer for the author of Blairism’s recollections.

Fleet Street resounds to just one gag today: every ash cloud has its silver lining. Tony

Blair is marooned in the Middle East and won’t be plugging his memoirs at this week’s London Book Fair. I wonder if he’ll adopt a few Semitic shrugs to accompany the gauche Cary

Grant accent. Still, we must wait longer for the author of Blairism’s recollections.

Blair may have degraded into self-caricature, but his premiership deserves a literary legacy. It was dominated by thrilling conflicting narratives. Blair’s obvious political skill was matched by convictions over which the three parties still battle: public service reform, choice and eradicating entrenched social divisions to name but three. Blair’s way may or may not have worked, but Gordon Brown connived to ensure that Blair could never be the pivotal leader he aspired to be. Equally, Blair could never realise his ambition because he was too insecure to sack Brown. Andrew Rawnsley’s End of the Party gets close, but that story of envy and weakness, that dissection of power, and therefore competence, remains unwritten.

Alistair Campbell’s diaries are fascinating if only to convey the banality of government – I lost count how often he mentioned being woken by some acolyte at 6:30 to tell him that the Today programme was going well, or that some nonentity was on the phone quipping about EU farm quotas. His perceptions are wedded to the movement he created and sustained, which is no bad thing but he’s not objective – WMD being a case in point.

Peter Watt’s memoirs read like Bridget Jones Goes to Whitehall. The hapless man is cast against a faction that oscillates between callousness and intimidation. It’s horrific, grim and depressing – a factual Lord of the Flies. Whether by chance or design, Watt provides the least flattering portrait of Gordon Brown. It’s insightful but rinsed with emotiveness – Watt wrote seeking catharsis as well as in self-defence.

Chris Mullin’s vivacious diaries are first rate on the personalities in the massed Departments for Paperclips and Folding Deck Chairs. Gus O’Donnell is ubiquitous – the Civil Service transformed. John Prescott is a blustering incoherent, carping on in a meeting ignorant to the fact that his shoes aren’t a pair. Yet A View From The Foothills is as its title suggests. You dip into it and come up for air with the conclusion that junior ministers knew only fractionally more about their government than you did. I wonder if more definitive work on Blair will reach the same conclusion?

Comments