There are an estimated 417,000 people in the UK suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and double that number suffering from other forms of dementia.

There are an estimated 417,000 people in the UK suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and double that number suffering from other forms of dementia. Potentially there are a large number of readers for John Suchet’s touchingly honest account of his wife’s slide into dementia, but — and here is the irony — it will not be the victims themselves of these diseases who will perhaps find comfort or insight from his book but the million or more carers who look after them.

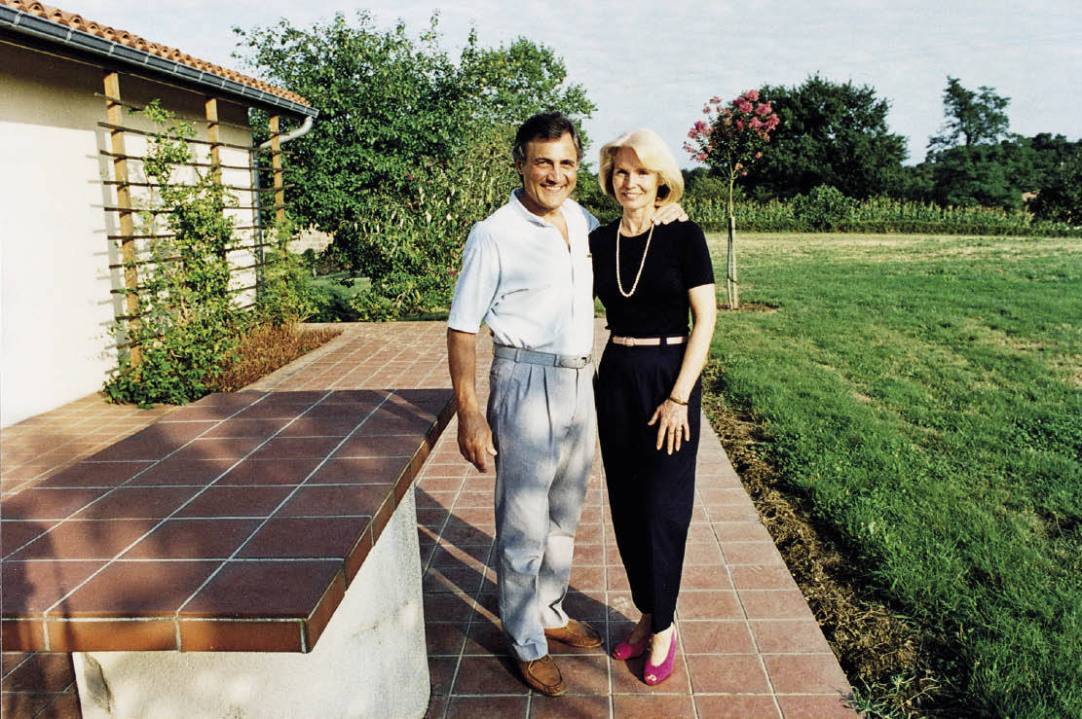

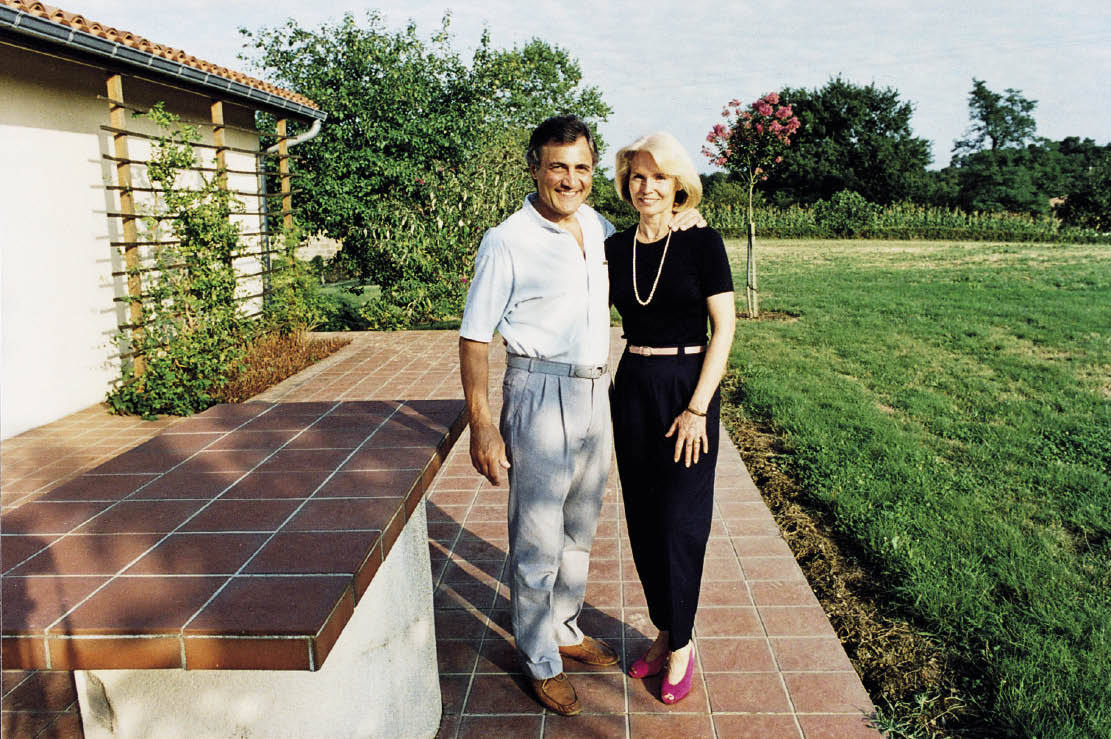

John Suchet is a famous television journalist and former newscaster for ITV. He is the brother of the actor David Suchet and author of several works on Beethoven. While still married, and with young children to look after, he fell in love with Bonnie, a strikingly beautiful woman who lived near him in Henley, who was also married and also had a family of her own. It was love at first sight. A powerful and irrepressible physical attraction drew them together. There were difficulties and divorces that both had to go through before they could be together, but despite some financial hardship, and a blip in his career as a television journalist, they were finally able to marry in 1985 and build a life together in a flat in London and a farmhouse in Gascony.

For a time all went well. Both had good, challenging jobs. Both enjoyed travelling and visiting their French idyll. To those who knew them then they must have seemed the perfect couple. He, strong and virile, with a good speaking voice like his brother’s, a natural broadcaster. She, slim and beautiful, with a wide smile, good nature and that grace which seems to be one of the defining characteristics of women born on the East Coast of America.

Then, six years ago, Bonnie began to show the first signs of confusion — small things, like loosing her way in an airport. But, as I know only too well myself, these small signs which one is apt to dismiss with a laugh and a joke — ‘must have Alzheimer’s’, we say as we desperately look for the keys to the front door — are a warning, and in 2006 Bonnie was diagnosed with this dreaded condition.

She took the diagnosis with remarkable good grace and, again, there is an irony about the situation Suchet found himself in. The sufferer can be blissfully unaware that they have a serious, life-destroying problem. It is the poor carers or partners (don’t you just hate those words?) who suddenly find themselves confronted with challenges for which they have no prior training.

In Suchet’s case he found that he was now not only the breadwinner but also the bread- maker, and having lived most of his life as a journalist on the run, his answer to cooking seems to be to take something from the freezer and pop it in the microwave.

That is the easy part. As the symptoms worsen, the carer, if he is a male, has to learn how to do the shopping and other domestic duties; worst of all, how to mop up after a bout of incontinence. He also has to organise such social life as remains and make all the plans and travel arrangements. ‘So what?’ I can hear some wives say. ‘We have to do that all the time’. To which I can only answer rather lamely that, past 60, old dogs find it hard to learn new tricks.

Being a good journalist, Suchet does not flinch from describing the bad side of watching the love of his life slip away from his grasp. Writing in short, staccato passages he tells of his bafflement at the effects of his wife’s memory loss, his mood swings, the anger which can boil up inside him, the demeaning tasks that have to be performed, the lack of sleep brought on by anxiety and by Bonnie’s restless wanderings as her condition worsened, his tears when he was reminded of some romantic moment from their past life together, and the feelings of guilt when finally he decides to put Bonnie into a home. It is not great literature, but the writing is honest and the emotions he has been put through over the last four or five years are, I can testify, ones which many carers will recognise in themselves.

However, it is not all gloom, and he intersperses his account with the story of how he fell in love with his wife and the struggles he had to endure before they could marry. Indeed, if you were to look at the photographs in the book, you might think his life with Bonnie has been one long party.

To his credit, also, Suchet has not flinched from ‘coming out’ with his story, and in the process has become an eloquent ambassador for Admiral Nurses, the organisation which helps carers navigate their way through the bewildering process of dealing with dementia and the legal and social ramifications it gives rise to. He is an active fundraiser, and is now Honorary President of Dementia UK.

Comments