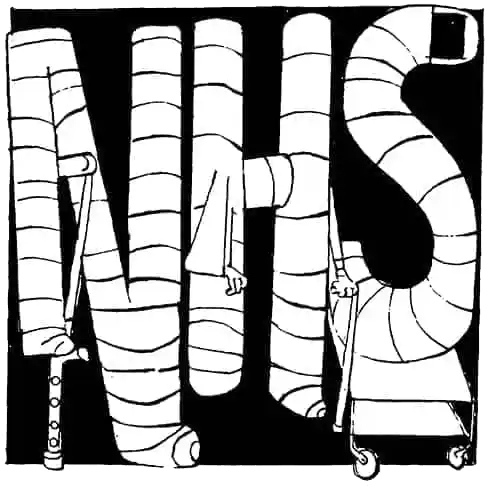

There is a war being waged in NHS hospitals. On one side are overstretched junior doctors in understaffed wards. On the other: physician associates (PAs) or, to use the more disparaging term, ‘noctors’.

Since 2003, non-medical graduates have been able to gain entry to hospital wards and GP practices if they complete a two-year clinical course that leaves them a ‘physician associate’ or ‘anaesthesia associate’. At first, PAs were rare – ten years ago there were fewer than 150 in England. Since the pandemic, however, the numbers have exploded. There are now approximately 4,000 PAs working in England and Wales.

PAs are supposed to help doctors with the time-consuming administrative work. Instead, many medics argue that they are stealing training opportunities from medical practitioners. Junior doctors complain about low pay, with foundation-year medics until recently beginning on a base salary of around £28,000 – while physician associates now start on £46,000. Graduates who have completed at least five years of medical school are expected, in some hospitals, to answer to non-doctors who have completed something akin to a clinical crash course. And medics keen to pick up training opportunities for speciality training applications have been pushed out of procedures while PAs benefit.

The already troubled relationship between doctors and PAs reached a nadir this month when pro-euthanasia politicians rejected an amendment to the assisted suicide bill that would have insisted only fully qualified doctors sign off applications. MPs fear that non-medics could be the ones deciding who lives and who dies.

It’s not just doctors who should worry about the influx of PAs in hospitals. Cases of medical mismanagement at the hands of physician associates are stacking up. In 2023, 30-year-old Emily Chesterton died of a blood clot after being misdiagnosed by a PA whom she assumed was a GP. Chesterton exhibited ‘red flag’ symptoms of shortness of breath and calf pain, but the physician associate examining her didn’t spot the seriousness of her presentation. More alarmingly, the PA did not make it clear that they were not, in fact, a medical practitioner.

Last month, a coroner issued a warning about PAs after a woman with severe abdominal problems was wrongly diagnosed as having a nosebleed. She died four days later. In another case, Ben Peters, 25, died after suffering an acute aortic dissection – a tear in the biggest artery in the body – the day after he saw a PA in November 2022. While the hospital trust concluded that the physician associate had ordered all the correct tests, Peters’ case illustrated yet another example of a patient being discharged without seeing a doctor.

Employing PAs is a cheap and easy way to tackle the NHS staffing crisis, but it comes at a cost: patient care

There have been reports of PAs using the title ‘Dr’ despite having no right to do so. There are even cases where physician associates have been drafted into GP surgeries that had struggled to recruit clinicians. In fact, in a 2017 census by the Faculty of PAs, almost two-thirds of physician associates admitted they had been asked to cover trainee doctor rota gaps at hospitals. Tellingly, the question was ditched from subsequent surveys.

It’s the blurring of lines between PAs and doctors that worries medics. Some take issue with the job title, since in surveys patients say they think ‘physician associate’ sounds ‘grander’ than junior doctor. Lady Finlay, a palliative care doctor and fellow of the Royal College of GPs, suggested the role should be renamed ‘physician assistants’. (To make matters more confusing, there is already a doctor role titled ‘associate specialist’.)

Adding to the ambiguity, the General Medical Council – the body that polices doctors – became the statutory regulatory body for PAs last year. This move has caused much consternation in medical circles: the British Medical Association, the Doctors’ Association UK and the EveryDoctor group all opposed the decision.

‘What’s become increasingly clear is that by trying to refer to everyone as “medical professionals”, there is enormous confusion as to who is doing what,’ says Professor Philip Banfield, the BMA chair. He points out that the only legally protected title for a doctor is ‘medical practitioner’ – which sounds awfully similar to the umbrella term PAs now fall under.

‘The GMC has also declined to set the standard for what a non-doctor can and can’t do,’ adds Banfield, whose union is taking the GMC to court over the issue. ‘As you find more evidence of something being wrong in medicine, you don’t keep treating the patient when it’s not working. This is a patient safety issue. There’s a clear distinction between the amount of training, skills and expertise a doctor has compared with a physician associate. The associate professions should be supervised directly by a senior doctor – but that isn’t happening. What we’re seeing is doctors being substituted by PAs.’

The GMC is facing a separate legal challenge from Anaesthetists United, which has accused the medical regulator of ‘simply ignoring the law on professional regulation’. The Association of Anaesthetists, another organisation that has flagged concerns, has called for the GMC to ‘present doctors and PAs on separate registers’ and ‘protect every-one from accidental or deliberate misrepresentation’.

Doctors are disappointed by the actions of their regulatory body. ‘For some time now, doctors have lost confidence in the GMC as their regulator,’ says Banfield. ‘It doesn’t come as a surprise for the GMC to defend an indefensible position.’

There has been some relief at Health Secretary Wes Streeting’s decision in November to commission a review to examine whether the non-medics are working within their limitations. ‘The difficulty is that the only point at which we know what physician and anaesthesia associates can do is at the point of qualification,’ says Banfield. ‘After that, it’s entirely down to what an employer lets them do. So there’s no national scope of practice that puts the ceiling on what they can and can’t do. There is nothing stopping an employer training a physician associate to do a caesarean section, for example, and then two years later calling them a “consultant” – without any understanding of the underlying anatomy, physiology, pathology and things that can go wrong.’ The PA course skips the scientific foundations of medical degrees and its finals are more straightforward than first-year medical exams.

All major political parties are in favour of training PAs as a quick solution to staffing shortages. Under the last Conservative government, NHS England aimed to expand numbers to 10,000 by 2036, while the Scottish government says it is keen to ‘gradually’ increase numbers. More PAs on the wards mean staffing quotas can be met while weakening the bargaining power of doctors campaigning for better pay and conditions. Although PAs often start on higher salaries than junior doctors, there is less opportunity for career – and therefore pay – progression. As the exodus of medical trainees to countries such as Australia and New Zealand continues, employing PAs is a cheap and easy way to tackle the NHS staffing crisis. All this does come at a cost, however: patient care.

Flooding the system with less qualified medical staff makes incidences such as the death of Emily Chesterton more likely. ‘It symbolises the start of a greater sort of creep, of less qualified medical professionals doing things outside of their competencies,’ one practising doctor tells me. Even if these cases don’t end fatally, misdiagnosis further clogs the system with patients who need to return to their GPs or hospital.

There is also a worry that a ‘two tier’ system could evolve, with more rural, deprived areas being left under the care of non–medical graduates while the dwindling population of doctors are moved to big city hospitals. Dr Alison George, a GP from Newcastle, has warned of the evolution of a ‘doctor-lite’ service. ‘It’s a down-skilling, downgrading of healthcare which will affect people on lower incomes,’ she says.

While there are areas where overworked doctors would be desperate for extra help – from history-taking to administrative tasks – there is no future for a health service that sees physician associates acting like doctors. The insidious creep towards PA-led care must be tackled and the scope of PA practice must be clearly defined and regulated – or patients will be the ones losing out.

Comments