Jody Rosen lives and cycles in Brooklyn, which makes him what the Mexican essayist Julio Torri calls ‘a suicide apprentice’. He has been ‘rear-ended’ and ‘doored’ several times. He quotes an unnamed cyclist who likens the click of a car door being opened to the sound of a gun being cocked. ‘Get a bicycle,’ said Mark Twain. `You will not regret it, if you live.’

This rangy, digressive book contains just about the right amount of bicycle history and mechanics for the unobsessed. Rosen is not a bicycle fetishist. He can ‘barely patch an inner tube’, though he does enjoy the ticking-clock simplicity of the shiny contraptions which carry the flesh-and-bone engine far from the ‘alienating frictionless interactions’ of the digital age and back to ‘the tactile satisfactions of machine-age technology’.

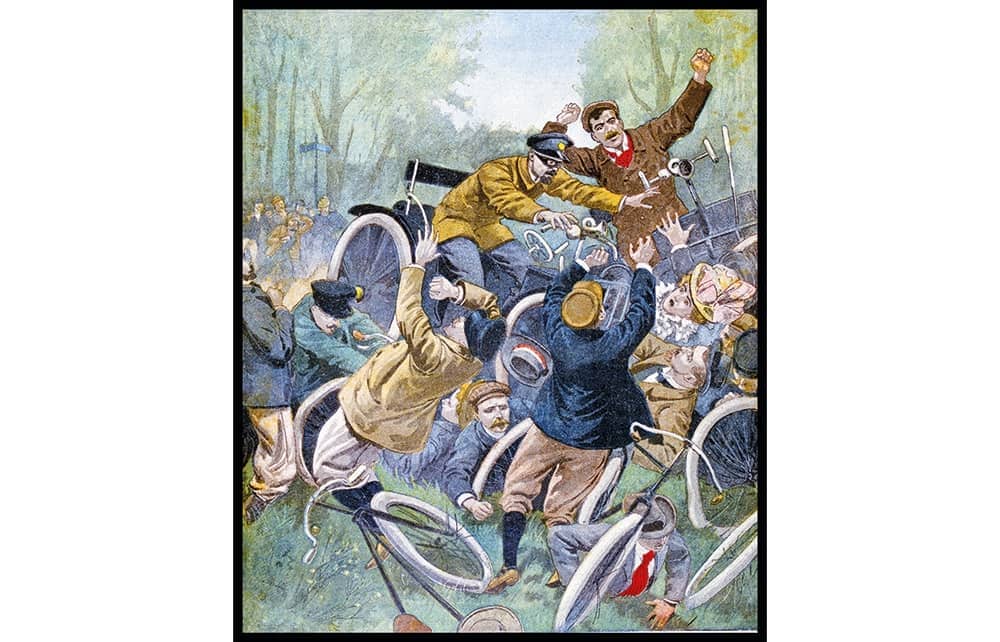

The ‘feedless horse’ or, to Flemish-speakers, ‘floss-horse’ (from ‘velocipede’) acquired its modern form in the 1880s. It was cheap, clean(ish), nearly noiseless and, before the advent of carbon frames, endlessly repairable. It liberated the masses and cheered them up. Women became dangerously mobile. ‘Cycle tracks will abound in Utopia,’ wrote H.G. Wells in 1908. The horse lobby was reduced to lame objections: ‘You cannot pet a bicycle’ (actually, you can), and, unlike a real horse, it falls over when it stops.

In the US, the best way to kill someone with impunity is to use a car, if you’re sober, and your victim is riding a bike

For Rosen, riding even a clunky bicycle is ‘better than yoga, or wine, or weed. It runs neck and neck with coffee and sex’. As an ‘antidote for writer’s block’, it can’t be beaten. That ‘quaint, even cute vestige of the Victorian world’ can, however, turn the rider into an object of intense, murderous hatred and give a taste of what it feels like to belong to a persecuted racial or sexual minority.

The ‘mystery’ part of the book’s title seems to refer to the inexplicable antipathy of the motorised to the self-propelled. A recent Australian study of global cyclophobia found that 49 per cent of non-cyclists regard cyclists as ‘less than fully human’. Those annoyingly healthy, high-speed alien insects are treated in some countries as a plague of anarchists. According to an alarmingly vague statistic issued by the World Health Organisation, between 20 and 50 million people are injured, disabled or killed by motor vehicles every year.

In the United States and, less obviously, in Britain, the best way to kill someone with impunity is to use a car, provided that you are sober and your victim was riding a bike. In 2021, law-makers in Oklahoma and Idaho ‘passed bills that grant immunity to drivers who strike protestors with their cars’. ‘Focus on the bicyclists’ was the order given to officers policing Black Lives Matter demonstrations in New York.

The NYPD apparently has a ‘long history of hostility to cyclists’. While their colleagues were snatching and wrecking protestors’ bikes to prevent ‘property damage and/or looting’, an elite unit of cyclocops was practising the ‘aggressive’ manoeuvres described in the Bike Squad manual. I was curious to know more about useful-sounding skills such as ‘the Power Slide’ and ‘the Dynamic Dismount’ and so I consulted the leaked instructor manual, which is a grammatical car crash but full of sound advice: ‘Get up to speed and aim for target.’ ‘The speed of the dismount’ should match ‘the rider’s running capability’. After dismounting, ‘lower the bicycle to the ground … This will prevent the bicycle from “ghost-riding”.’

Escaping from New York City, Rosen flies – on descendants of the machine invented by two bicycle mechanics in Dayton, Ohio, in 1903 – to various destinations of velocipedal interest. He interviews a rickshaw driver in Bangladesh, the snow-booted, reindeer-dodging cyclists of Spitsbergen, the Scottish stunt cyclist Danny MacAskill and a racing cyclist in Bhutan, which the government intends to turn into ‘a bicycling culture’ in defiance of the Himalayas. He also visits China where, in 1978, Deng Xiaoping promised ‘a Flying Pigeon in every household’.

The lumbering ‘Pigeon’ was copied from a 1932 Raleigh Roadster. It was once `the most popular mechanised vehicle on the planet’. Now, in a Great Leap Backward, the nation which boasted 225 million cyclists is pursuing a policy of ‘de-bikeification’ (Rosen’s term), converting bike lanes to car lanes and promoting the idea, common in Britain not long ago, that the pushbike is a sign of economic and personal failure. A car-addicted contestant on a Chinese dating show in 2010 snubbed the suitor who invited her on a bike ride with the catchphrase: ‘I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle.’

The engaging tone of Rosen’s memoir-travelogue-history is the grim cheerfulness of the urban cyclist. He gives a vivid sense of the cinematic pleasures of cycling through a city. His loosely-jointed gleanings and observations have an accelerated window-shopping intensity. I was particularly distracted by the pedal-operated food-mixer and the eerily convincing acoustic accessory which consists of two pieces of coconut shell attached to the front brake mount of the feedless horse.

Comments