Under David Remnick’s editorship, the New Yorker has become stronger than ever during a period where many titles have collapsed. So you’d think he might be able to fend off the kind of nonsense he’s just experienced. The New Yorker has branched out to publish unmissable podcasts, regular emails, blogs and events which combine to push the magazine sales up 10pc. Remnick hasn’t torn it up and started again. He managed to keep everything the same, by changing everything: projecting and protecting the magazine’s identity, on and off the page.

So when he decided to conduct an interview with Steve Bannon live on stage, as part of the New Yorker Festival, it was a typically gutsy decision. He’ll have known that a good chunk of the staff would feel queasy about this, given how Bannon is spoken of as some kind of political antichrist. But objectively, who could doubt that Bannon is worthy of an interview? He’s a former chief strategist to Donald Trump, and helped the President plot his path to power by spotting things that others missed. Remnick’s viral essay on the night of Trump’s election left no doubt about his own views of the President and his advisers. Yet he’s not a propagandist, he’s a journalist: he would interview someone with whom he violently disagrees because the process might throw more light on their rationale and worldview. And people read a magazine to understand, not just to jeer at enemies. Knowing your enemy is an important part of working out what’s going on.

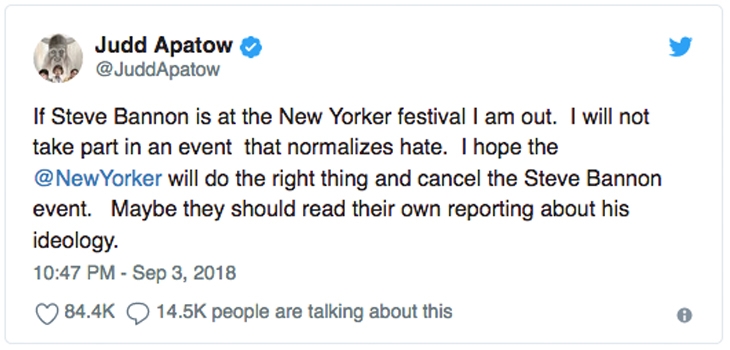

Yet when the Bannon interview was announced, the ensuing Twitterstorm produced its own momentum, leading to Bannon being dropped from the festival. The New Yorker’s readership is 1.2 million, and a tiny fraction of this number (most, I suspect, non-readers) used the ‘no platform’ rationale to say that giving Bannon a platform was to somehow endorse him. That his evil views could somehow corrupt the minds of New Yorker readers, tempting them over to the dark side. Enter the celebrities (Jim Carrey, Judd Apatow) expressing shock that acts of journalism might be committed in front of a live audience, and said they’d pull out.

Look at the language: to talk to and challenge someone who was running the White House not so long ago is ‘normalising hate’. The Twitterstorm then moved on to the New Yorker’s pressure points. Roxane Gay said that she’d pull out of an online writing project in protest. A few people talked about cancelling their subscriptions, hoping to whip up the prospect of a commercial threat. In large organisations this can spook the moneymaking people, who can overrule the editor. So Remnick issued a statement dropping Bannon saying he made a mistake. Having triumphed over Bannon, the Twitter trolls are now gunning for Remnick himself, saying he should resign for even thinking of talking to an ideological foe.

Set aside the fact that New Yorker’s readers (I’ve been one for 20 years) expect a magazine rather than a safe space. The idea that censorship is preferable to critical exposure runs contrary not just to the traditions of the New Yorker but to those of journalism and a free society. There are many quotes by American thinkers and judges about sunlight being the best disinfectant, about the most important freedom of speech being freedom for the kind of speech you hate. But the problem with no-platforming is perhaps summed up best by Peter Tatchell: ‘The best way to challenge bad ideas is with good ideas. If you simply ban someone, the ideas do not go away, and their supporters are not disabused of those ideas.’

It is growing harder to protect free debate. Social media has focused pressure on media organisations’ points of least resistance, with the aim of narrowing the parameters of debate. It’s bad for journalism, bad for America and bad for public debate in general.

Remnick is one of the most successful editors in the long history of the New Yorker, and his idea of interviewing Bannon on stage in front of a live audience was in the magazine’s finest traditions. A lot of the world has been surprised, even gobsmacked, by recent political events in Britain, in the US and on the continent. This suggests a deficit of understanding – a problem that can be addressed by good journalism. That’s what Remnick was seeking to apply and this is what his detractors succeeded in preventing. As Remnick’s old newspaper is fond of saying, democracy dies in darkness.

Comments