The late Sir Roger Scruton often pronounced in a harsh manner on modern architecture and modern music, perceiving in various work an assault on bourgeois culture and a break with tradition. Back in the 1950s, music critic and CIA agent Henry Pleasants (a station chief in Bonn) delivered if anything a more scathing view of the ‘agony’ of modern music, arguing that it had severed its connection with the idioms bequeathed by the human voice.

It might seem natural that opposition to the iconoclasm of artistic modernism would go hand-in-hand with a relatively conservative politics. Furthermore, knowledge of Nazi attacks on Entartete Kunst suggests a clear disjunction between far right politics and modernist art. Yet the reality is considerably more complex, and in an era in which promoters, curators, critics, academics and others are obsessed with eliciting and judging the underlying politics of all types of art, it is worth rethinking the association.

Mies van der Rohe attempted to gain Nazi support for the Bauhaus

Modernism came to fruition in Europe at the same time as the advent of mass education and literacy, democratising tendencies in Western societies, expanded industrialisation and the growth of major cities, as well the new imperialism associated with subjugation of parts of Africa and Asia. The term also gained currency due to its employment within Catholicism, whereby it was used primarily to denigrate aspects of urbanity, sophistication, cosmopolitanism and the adoption of technological and industrial life, leading to a denunciation by Pope Pius X in 1907.

Early modernists reacted to the new world in a variety of manners. Many adopted an ambivalent view towards a society that forced artists to be outsiders. Some retreated into a neo-aristocratic sensibility or denounced the ‘crowd’. Critics have argued that a range of modernists were especially hostile to the growth of ‘mass culture’ (in the form of popular music or theatre, newspapers, undemanding romantic novels, etc.), not least because of what these betokened in terms of a perceived new ‘feminisation’ of society. Some of this outlook is anticipated in the work of Baudelaire and Nietzsche. Their critique of bourgeois society was, according to some, fuelled as much by antipathy towards the new status, prominence, and consuming power of women and members of the lower classes as by any critique of the reign of capital. In response they cultivated various forms of highly demanding, sometimes esoteric, art forms, rejecting earlier nineteenth-century manifestations of subjectivity which might be associated with vulnerability or sentimentality – qualities constructed as feminine – in favour of bold and ‘objective’ new art forms.

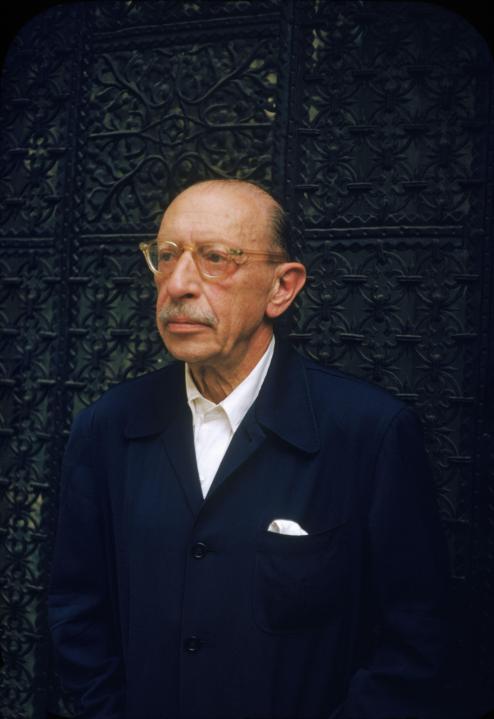

Those modern artists who explicitly supported or advocated the politics of the fascist right, including writers Ezra Pound, Knut Hamsun, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Yukio Mishima, artists Filippo Marinetti, Mario Sironi and Emil Nolde, or composers Igor Stravinsky and Anton von Webern, are not so many in number. Nonetheless, in many of these cases the connection between aesthetics and politics ran deep. Pound viewed Mussolini as a contemporary equivalent of 15th century nobleman, military leader and artistic patron Sigismondo Malatesta, and it has been plausibly argued that his view of Italian fascism was that it would ‘conquer modernity in the name of order’. Stravinsky, meanwhile, who met Mussolini and expressed his great admiration (‘I told him that I felt like a fascist myself’) found a similar sympathy with his own authoritarian world-view, tied to cults of primitivism and a disdain for modern manifestations of individual subjectivity. Marinetti’s futurism was predicated upon a cult of hyper-masculinity, explicitly glorifying war and displaying a ‘contempt for women’.

Other artists demonstrated varying degrees of complicity or complacency as fascism engulfed Europe. Architect Mies van der Rohe attempted to gain Nazi support for the Bauhaus, for essentially opportunist reasons which were ultimately unsuccessful, while composer Carl Orff attempted to have his Schulmusik adopted by the Hitlerjugend. There is no evidence of any ideological commitment to Nazism on the part of either, but nor did their artistic agenda lead to any particular form of opposition or resistance. While many prominent Nazis were pathologically opposed to many types of modernism (associating it with the despised Weimar Republic and opposition to German nationalism), the situation was less clear-cut in other fascist countries, above all Italy.

Artist Giorgio de Chirico acidly declared that Italian fascists were ‘modernists enamoured of Paris’; their model was the city state of ancient Rome, and they certainly championed certain forms of modernism in painting, architecture, music, and theatre that adhered to a monumentalist, ritualised and/or technocratic bent. In Germany not all shared the communitarian and anti-urban tendencies of Hitler or Alfred Rosenberg; the likes of Joseph Goebbels, Albert Speer or Reichsmusikkammer director Peter Raabe were by no means uniformly hostile to modernity, the city, and new means of artistic expressionism. Goebbels, together with Hermann Goering, was part of a committee which organised an exhibition in Berlin in late 1937 (just a few months after opening the first Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich) of Italian art from 1800 to the present, including a range of work embodying distortion of vision, caricature, abstraction, sexuality and unsettling subject matter, but this incurred the wrath of Hitler and was described as a ‘fiasco’ by Mussolini after he read a report. Raabe, when a conductor in Aachen in the 1920s, had conducted works of Schoenberg, Hindemith and Scriabin, been impressed by Berg’s Wozzeck, and in a book on Music in the Third Reich was by no means wholly hostile to musical modernism.

Many on the left took to modernism much more thoroughly and deeply. For a short period, the Proletkult movement in the early Soviet Union viewed new artistic means as necessary to the creation of a new ‘proletarian art’, creating a climate which nurtured the likes of poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, composer Nikolai Roslavets or film director Sergei Eisenstein. Surrealist painters and writers, especially movement founder André Breton, linked their aesthetic manifesto to communist politics. Artists in Weimar Germany, traumatised by the First World War and the failure of the attempted communist revolution in November 1918, pursued an art which presented distorted and unattractive images of mutilation and commercialised sexuality as a means not so much simply of reflecting the world as reflecting critically back upon that same world. Intense debates occurred among a range of Germanic and Hungarian thinkers, including Ernst Bloch, Theodor Adorno, Bertolt Brecht, Walter Benjamin and György Lukács as to the meaning or relevance of plural aesthetic movements as a response to a perceived advanced capitalist world in crisis.

Furthermore, the work of many of the non-leftist artists mentioned above – who we now know to have exhibited questionable allegiances and sometimes dangerous ideologies – has continued to exert a fascination upon later generations who in no sense shared such politics, as witnessed for example in the profound interest of American poet Jackson Mac Low in the work of Pound. These earlier artists’ works may have been informed in part by such politics, the work may even embody aspects of it, but cannot usually be contained by it.

Following the dual traumas of fascism and Stalinism, a good deal of Western art for several decades after the Second World War showed little attachment to wider programmes for social transformation, nor to explicit political causes, instead embodying a more abstracted world-view, somewhat alone and isolated in the manner of the earlier modernists and romantics, but without the same will to change. Examples of such artists would include writers Samuel Beckett, Peter Handke, Charles Olsen and Lorine Niedecker, composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and Elliott Carter, film directors Michelangelo Antonioni and Wim Wenders, or dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch. The work often epitomised deeply internal responses to the world, the elaboration of private mythologies, and sometimes thwarted searches for meaning, none of which could easily be tagged to a specific political agenda.

The strength of modernism lies not in its commitment to one set of politics but in its polyvalency

Nonetheless, such work stood in profound distinction to the demands placed on artists in the Soviet Bloc following the Zhdanov decrees of the late 1940s that censured ‘formalism’. The publication of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Qu’est-ce que la littérature? (1948) did stimulate a debate on the value of arte impegnata (committed art) among those with communist sympathies, culminating in a short period in which some artists adopted a Zhdanovite rejection of modernism, while others including composer Luigi Nono or director Jean-Luc Godard found means of reconciling modernist techniques with subject matter relating to radical politics. But during the Cold War era one could find pronounced antipathy to the left on the part of composer Milton Babbitt (who is once alleged to have described himself privately as ‘to the right of Marie Antoinette’), while film director David Lynch openly supported Ronald Reagan, and dystopian novelist J.G. Ballard declared his admiration for Margaret Thatcher. In the West today, aesthetic debates have taken a back seat to those about issues of diversity, inclusivity, identity, ideology, and ‘relevance’, coupled to attempts to link art to contemporary issues.

The meaning of modernism outside of the Western world is equally variable. The study of ‘global modernism’, exploring not only extensions of a Western movement into the wider world, but ways in which modernism can be said to have global cultural roots, is a relatively recent but energetic branch of scholarship. As early as the 1880s writers such as the Cuban Ramón Perés or Nicaraguan Rubén Dario were developing their own use of the term modernismo in part in opposition to the culture of the former colonial power of Spain. Some of the most avant-garde art and architecture from various regions of Africa draws as much upon indigenous traditions as Western ideas, as can equally be said of many varieties of East Asian modern art, literature, theatre and dance, some of which had a profound influence upon Western modernists. But in some traditionalist or censorious societies, there is less of a place for the flourishing of an avant-garde that is sometimes viewed as representing a colonising force.

Modernist art has been linked to politics across the spectrum throughout its history. But the strength of such art lies not in its commitment but in its polyvalency, its potential for provoking a plurality of meanings, perspectives, emotions, thoughts. To reduce such work to a particular politics is to force it into a narrow box. Such attempts to contain and judge ultimately deny that open exploration and generation of forms of experience which add something new to the world which is so characteristic of modernism viewed most broadly

Comments