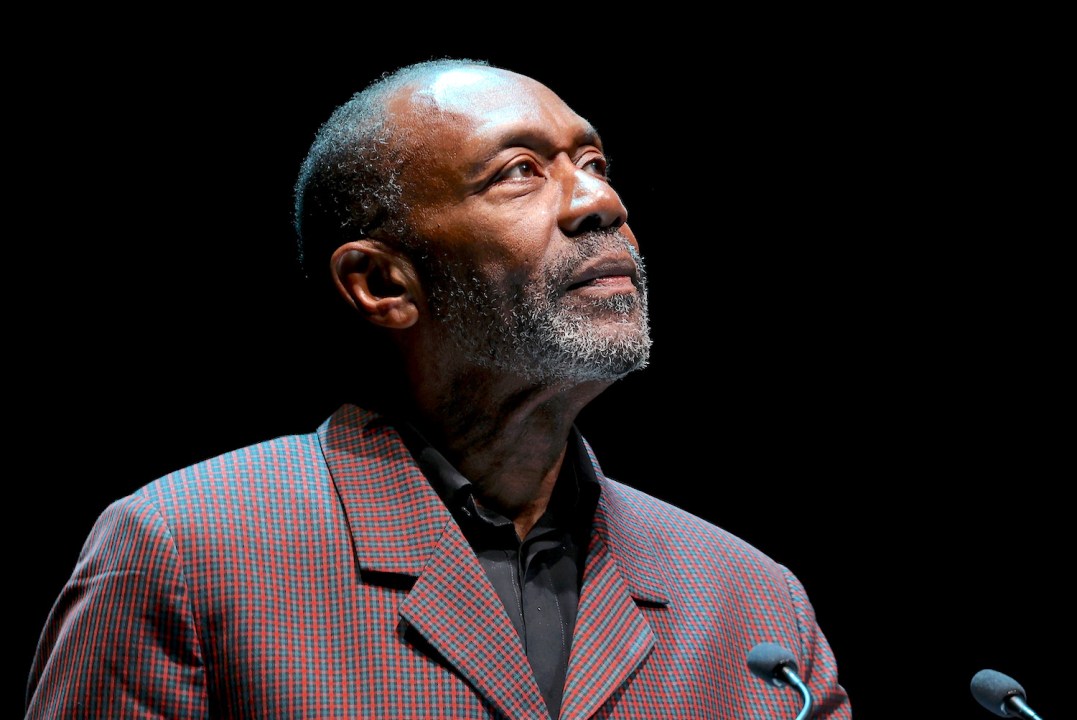

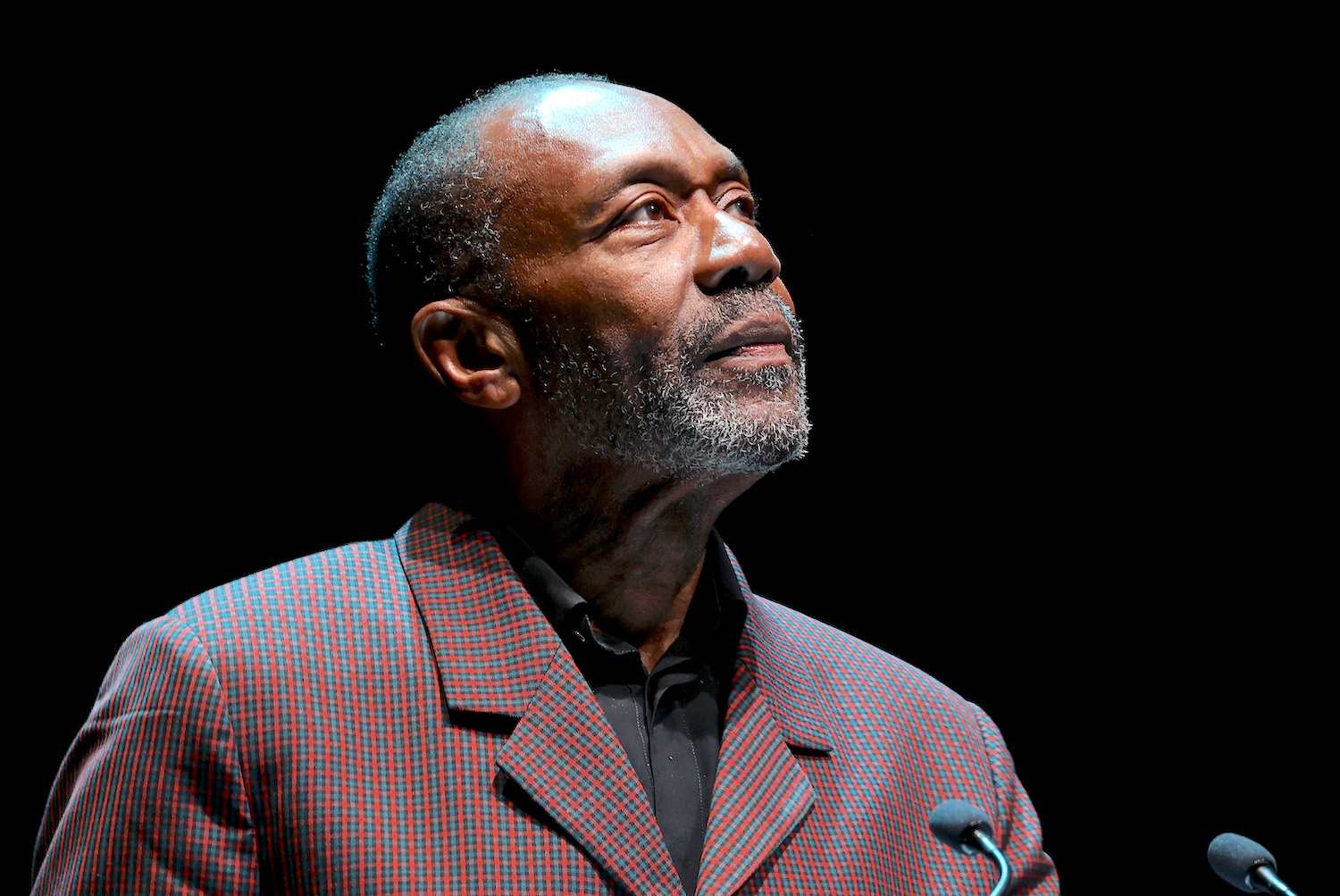

The desire to seek restitution from those who have harmed or wronged us is normal. Our instinct for justice is inbuilt. Yet, in recent decades, there has emerged in the West a perverse distortion of this impulse: the demand for financial compensation from people who have done no wrong, made by people who have not been wronged. Long-established campaigns calling on Britain to pay reparations for slavery are founded on this strange premise, and the latest figure to join their ranks is Sir Lenny Henry.

The comedian and actor makes his case in a new book, The Big Payback, co-authored with Marcus Ryder, a television executive and charity boss. He argues for the UK to hand over £18 trillion in compensatory payments. As reported in the Telegraph this morning, Sir Lenny not only calls for this huge transfer of money to Caribbean nations, but for cash to be given to individual black British citizens, because ‘all black British people… personally deserve money for the effects of slavery’.

He elaborates: ‘The reason we have racism today and also… why black British people are grossly over-represented in the prison population [is] all because of the transatlantic slave trade’.

Really? First of all, the assumption that Caribbean nations underperformed since independence because of the economic and mental legacy of slavery is highly debatable. Their post-independence fortunes owed as much to the competence of their rulers as any putative ancestral memories: Barbados largely flourished, while others, such as Jamaica, didn’t, because the latter was governed badly. As for the popular hypothesis that the descendants of slaves have, through mysterious osmosis, ‘inherited’ the mental scars of that far-off experience, this merely echoes another fashionable yet highly contested theory prevalent in our therapeutic age: that the ‘trauma’ of our own past and of our ancestors irrevocably determines our behaviour today.

Sir Lenny is on even flimsier ground in arguing that all black people in Britain deserve compensation because slavery and its folk memory has condemned them to a life of underachievement, failure and incarceration. This is refuted by the simple fact that most black people in Britain aren’t of Caribbean heritage. The majority of black Britons today are of African descent, constituting 2.5 per cent of a total 4 per cent black population. Some, therefore, will be the descendants of those who were active and complicit in that era of mass human trafficking.

During the transatlantic slave trade, West African states sold in profusion their captured enemies to European and Arab traders. Among the big players were the kingdoms of Dahomey and Whydah (both located in modern day Benin). King Gezo of Dahomey, who reigned from 1818 to 1858, even once boasted – in the face of British demands to end this practice – how his kingdom owed its prestige to the business of selling humans: ‘The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth.’ Those who cleave to the logic of reparations based on ancestral crimes should also be asking modern states in West Africa to make financial recompense.

We are all descendants of sinners and the sinned against

Campaigning for the offspring to compensate for the sins of their forefathers is an enterprise fraught with difficultly. Not only will some black Britons today be the offspring of slave traders, but the very category ‘black’ has become ever more fluid and elusive, considering the generations of intermarrying and mixing that have taken place since the 1940s. ‘Mixed race’ may be an imperfect-sounding category, but it does increasingly represent a more accurate description of a large demographic in Britain today.

In the long run, also, we are all descendants of sinners and the sinned against. To crudely bracket people living in Britain today as belonging to either camp makes no sense. My mother is Irish and my father was English. So should I demand compensation for the Potato Famine, or should I be required to atone for it? Am I a victim or a villain? I would be grateful if Sir Lenny could answer that one. Activists, actors and governments who make noisy demands for reparations, motivated often by grievance and resentment, and sometimes by greed and opportunism, never seem to move beyond emotive language and simplistic arguments riddled with holes. Their solutions only beg more questions.

Comments