This is not a good time to be a girl. Research from Steer Education last month showed that far too many girls are sad and anxious and concealing their troubles from others.

In 2019, the Lancet published research showing girls’ rates of self-harm had tripled since 2000. Other studies show girls are much more likely to be depressed or anxious than boys.

This might surprise. Aren’t today’s girls growing up in an age of equality, inheritors of girl power? They’re more likely than boys to go to university. They have better economic prospects than any generation of females that went before them. Empowered female role models are more visible than ever before, in culture, sport, media, science, business, even politics.

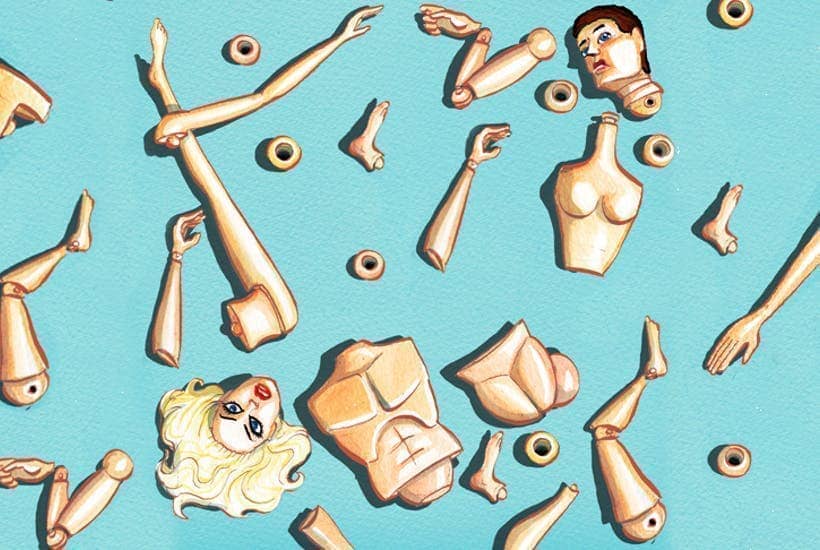

Yet at the same time, girls are growing up in the digital age, where images of what women and girls can (or perhaps should, depending on your view) be are everywhere. From the earliest age, many of those images are strongly sex-based, assigning roles and characteristics to girls because they are girls. You can tell a story here that starts with pink unicorns for toddlers and ends with Instagram and YouTube influencers who can make millions selling an image of apparently perfect, glossy femininity.

Does that culture contribute to that epidemic of mental health problems for girls? It’s notable that the Steer Education research found ‘unhealthy perfectionism’ is a key driver of girls’ distress: many feel under crushing pressure to be the perfect girl or woman. But this is still just speculation. I don’t know what’s causing mental health problems among girls. I don’t think the evidence is clear. We don’t yet have a good explanation.

Here’s something else involving girls that is unexplained. More and more of them are saying they don’t want to be – or don’t feel like they are – girls. As societal images of female perfection become more powerful and pervasive, more girls are identifying out of being female. Across western societies, the last decade or so has seen a sharp rise in the number of girls presenting with gender-related conditions, sometimes receiving treatment from gender clinics.

On puberty-blockers and hormones, Cass has not yet reached firm conclusions on treatments

In the UK, that largely means the NHS Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) in London, sometimes known as the Tavistock. Broadly speaking, a few years ago, GIDS saw more male-born children than female ones. These days, the children who make up GIDS’s much larger caseload are more likely to be female-born: the caseload is sometimes almost three-quarters female. It’s a generalisation, but gender treatment used to be about looking after male-born people who said they didn’t feel male. Now it’s about female-born people who say they don’t feel female.

This is a hugely important part of the story around GIDS, children and gender, and not just because no one really knows what’s caused that shift. It’s important because of what it means for the evidence base that clinicians and others have on gender issues and their treatment.

By definition, it takes a long time to understand the effects of a developmental or clinical intervention involving a child or adolescent. In the context of gender issues, such interventions can include medicines to block puberty and cross-sex hormones that encourage the body to develop some of the sexual characteristics of the opposite sex.

The use of such treatments is controversial and contested. As a result, NHS England in 2019 launched an independent review of those treatments for children and young people, a review later expanded to take in the services that deal with children and gender, mainly GIDS. That independent review is led by Hilary Cass, a retired consultant and former president of theRoyal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

The Cass Review published an interim report this week. A lot of the coverage of that report focuses on GIDS and its capacity to cope with its enlarged caseload. Some of it rightly notes that the – independent and authoritative – report largely vindicates the whistleblowers, campaigners and journalists who spent several years raising legitimate concerns about the way the clinic was operating. Many of those people faced criticism and worse from people close to the Tavistock clinic. Culpably, it was sometimes implied that people raising concerns about the clinic’s treatment of children were motivated by bigotry or politics.

The Cass report proves that people raising concerns about GIDS were justified, since it finds a service often failing at the most basic functions. Poor or absent records mean the clinic doesn’t know what happened to the children it was treating:

There has not been routine and consistent data collection within GIDS, which means it is not possible to accurately track the outcomes and pathways that children and young people take through the service.

The final Cass Report will clearly spell the end of GIDS in its current form. But the fate of one NHS clinic is not the most important part of the Cass work to date.

To me, the truly disturbing message that emerges from the interim report is confirmation of just how little is known about the female-born children who are now most of the gender-clinic caseload, and about their treatment and its consequences.

And that is because most of the patchy evidence base on gender issues and treatment is based on people who were born male. And to state a fact that shouldn’t need to be stated, male humans and female humans are different, physically and developmentally. The interim report notes:

Much of the existing literature about natural history and treatment outcomes for gender dysphoria in childhood is based on a case-mix of predominantly birth-registered males presenting in early childhood. There is much less data on the more recent case-mix of predominantly birth-registered females presenting in early teens, particularly in relation to treatment and outcomes.

On puberty-blockers and hormones, Cass has not yet reached firm conclusions on treatments she describes as ‘life-changing and innovative’. But she writes:

It is also important to note that any data that are available do not relate to the current predominant cohort of later-presenting birth-registered female teenagers. This is because the rapid increase in this subgroup only began from around 2014-15. Since young people may not reach a settled gender expression until their mid-20s, it is too early to assess the longer-term outcomes of this group.

When discussing the Tavistock clinic and the work it does, it is easy to slip into intemperate language – the treatment of sometimes vulnerable children is inevitably an emotive issue. Cass rightly notes that a climate of polarised opinion on the topic doesn’t do anyone any good:

The disagreement and polarisation is heightened when potentially irreversible treatments are given to children and young people, when the evidence base underlying the treatments is inconclusive, and when there is uncertainty about whether, for any particular child or young person, medical intervention is the best way of resolving gender-related distress.

I take that point seriously, so all I will say in conclusion here is that I hope the measured and independent analysis of the Cass Review is taken very seriously by everyone involved in debating this issue and making policy around it. Because I think it highlights something important and troubling.

Life-changing and sometimes irreversible medical treatment is being administered to a growing number of females, without evidence for how that treatment will affect females but mainly on the basis of limited evidence about how such treatments affect males. And the people administering that treatment don’t even know why so many of their patients are female.

If this is not a good time to be a girl, that must surely be at least partly because quite a lot of people who really should do better don’t appear to care very much about girls and their welfare.

Comments