In late 2018 a Saudi journalist living in exile in Canada, who liked to work out in between recording YouTube critiques of his government, ordered some protein powder online. When a text message landed on Omar Abdulaziz’s smartphone notifying him of a DHL delivery, he clicked on it without hesitating.

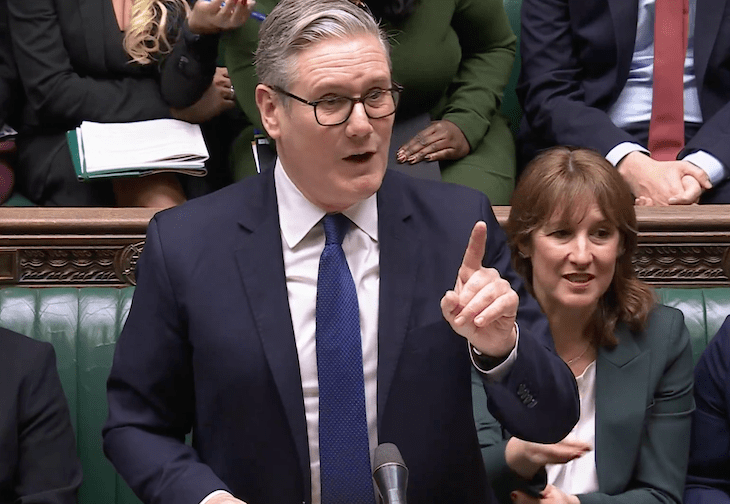

The portrait Deibert paints is a million miles away from the Cold War binary world of John le Carré

The DHL invitation was fake digital bait. By clicking on it, Abdulaziz had enabled Pegasus, a spyware program designed by a now infamous Israeli company, NSO Group. It proceeded to hoover up his emails, contacts, photos and WhatsApp exchanges, which included discussions of a plan he was hatching with a friend to distribute SIM cards to supporters willing to take on Saudi Arabia’s ruler on social media. Abdulaziz is convinced that those eavesdropped conversations are the reason why his friend Jamal Khashoggi was killed and dismembered in the Saudi embassy in Istanbul by an execution squad dispatched from Riyadh, while his fiancée waited forlornly outside.

The story is just one of many in Chasing Shadows that will chill the blood of any journalist, human rights worker or civil society activist. Or, come to think of it, any ordinary citizen who believes that criticising your own government does not merit extra-judicial execution, and that private communications should remain private. Abdulaziz only learnt of his inadvertent role in Khashoggi’s murder thanks to the Citizen Lab, a digital forensics laboratory based at the University of Toronto. It is the creation of Ronald J. Deibert, ‘a working-class street kid from a hardscrabble East Vancouver neighbourhood’, who has dedicated his career to exposing international cyber espionage. His account makes for an utterly gripping, petrifying read.

The internet’s expansion and the ubiquity of smartphones have gifted dictatorships, intelligence agencies and corporations with hitherto undreamt of opportunities for spying. When combined with social media platforms that allow despots and oligarchs to anonymously spread disinformation, create moral panics and drown out genuine public opinion, digital technology has left civil society groups, human rights workers and investigative journalists fighting for breath. Deibert’s realisation that those being targeted were ill-equipped to detect, let alone combat, the threat prompted the idea of a laboratory offering ‘counter-intelligence for global civil society’. In 2001 he got the funding to set it up.

The portrait he paints is a million miles away from the Cold War binary world of John le Carré, where espionage was dominated by the superpowers. The relative affordability of digital technology means that espionage today has been both democratised and privatised. Instead of homing in on the US, Russia and China, Deibert focuses on the likes of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, Mexico, El Salvador and Spain.

You might assume that a tiny African nation such as Rwanda, for example, would have neither the desire nor the funds to play in this league, but you’d be wrong. President Paul Kagame was trained in military intelligence in the bush. His appetite for espionage explains why I, as a writer who has interviewed hundreds of Rwandan dissidents challenging Kagame’s air-brushed account of history, make a brief appearance in this book.

Carine Kanimba, the daughter of Paul Rusesabagina, the hotelier-turned-human rights campaigner kidnapped by the Rwandan government in 2020, was puzzled by the fact that Rwandan prosecutors seemed privy to conversations between her imprisoned father and his family abroad. The reason was simple, as the Citizen Lab and Amnesty International established after examining her phone. It had been infected with Pegasus.

NSO Group is a villain in this tale, and the state of Israel itself emerges as a prime facilitator in this dark and sinister world. Geographically surrounded by Arab enemies, Israel has poured investment into intelligence-gathering ever since its foundation in 1948. ‘Cybersecurity’ can be studied as a subject at both high school and university. Young Israelis with hacking skills are funnelled into military intelligence and then encouraged to branch out into the private sector. The hundreds of cybersecurity companies that result soak up not only former members of Israel’s secretive Unit 8200 but also former CIA, NSA, MI6 and KGB employees tempted by the chunkier salaries on offer.

There’s a fairly high nerd quotient to Deibert’s account, and some readers will struggle with its unfamiliar terminology. ‘Zero day events’ (cyberware attacks making the most of previously unrecognised software vulnerabilities) crop up repeatedly, and one swiftly becomes accustomed to the use of ‘exploit’ as a noun rather than a verb. But Deibert is good at providing illustrations of real-world impact whenever the jargon threatens to overwhelm, and the reader remains hooked.

There is some good news, as Deibert is at pains to stress. Thanks to the work of the Citizen Lab, human rights organisations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Access Now, and journalist groups such as Forbidden Stories and Bellingcat, awareness of this sinister industry has soared. Exposés have forced directors of intelligence agencies to resign, parliamentarians to launch inquiries and some of the dodgiest companies to become bankrupt.

A legislative breakthrough came in April 2023 when the US administration, which so often leads where others follow in matters digital, passed an executive order prohibiting federal agencies from procuring spyware used by foreign actors to target dissidents or curb political opposition. It represented an ‘epic loss’ for contractors hoping to gain a toehold in the US market. But that hard-won victory has clearly been jeopardised by the outcome of the US elections. Supreme executive power is now in the hands of a man who not only despises the mainstream media but cosies up to many of the despots happiest to use spyware to track, jail and kill their critics.

‘All of the progress that has been made in the United States combating transnational repression and regulating spyware abuses is now at risk of reversal,’ acknowledges Deibert. To add to the mix, new AI-enabled tools are making subversion cheaper and more effective. For a human being, drafting and tweeting 42 variations on a smear involves some effort. AI can do it in seconds – as I discovered when I came under just one such attack on X while on a New Zealand book tour last year.

Organisations such as the Citizen’s Lab are clearly destined to play a constant game of catch up, as shady new firms offering ‘deep background checks’ and ‘reputation management’ come up with ever cleverer ways of hacking into the devices we can no longer do without. But at least they exist. Towards the end of his book, Deibert focuses on the psychological toll that awareness of being constantly tracked and harassed takes. As one of those individuals – even if I sit in the second or third tier of these circles of intimidation – I can attest to the emotional wear and tear. Given the public’s widespread ignorance of the extent of this surveillance, loneliness is what makes the experience particularly trying. Knowing the Citizen Lab existed, and had my back, made a massive difference. Long may it thrive.

Comments