Dominic Cummings always saw civil service reform as an essential prerequisite to reforming the country itself. A year and a half after his departure, the Prime Minister has a new chief of staff who agrees. While different in temperament and style, both Dominic Cummings and his de facto replacement Steve Barclay have one under-appreciated similarity: a commitment to reforming government itself.

Last week, we saw the evidence of this commitment. With attention focused on plans to cut more than 90,000 civil servant jobs, Barclay quietly announced the most radical overhaul of civil service recruitment rules in over a decade. From now on, every single senior civil service vacancy will be advertised to external candidates.

All senior jobs are meant to have been advertised ‘externally by default’ since 2016. However, until last week, permanent secretaries had the authority to deviate from this rule. As my think tank, Policy Exchange, has highlighted, there was also a powerful incentive for senior officials not to advertise vacancies to external applicants, especially for positions that are highly prestigious. Save for limited exceptions, there is no independent oversight to assure the probity of appointments – or any legal obligation to select a candidate on merit – unless a civil service vacancy is advertised to external applicants. So powerful mandarins could opt instead to hire internally, promoting those who they trust and know to be reliable.

The proportion of appointments to the senior civil service from external applicants halved from 42 per cent in 2010 to 20 per cent in 2020

The Spectator has exposed an example of how Whitehall can operate like a closed shop. As Steerpike highlighted, one of the Cabinet Office’s most senior posts – the ‘Programme Director for Civil Service Modernisation and Reform’ – was filled in April 2020 without any competition whatsoever. Surely any ‘Director for Civil Service Modernisation’ would scrap such an uncompetitive appointments process? The PM’s new chief of staff certainly thinks so.

In fairness, some parts of Whitehall have embraced open recruitment. In 2014, for example, the Department for Communities and Local Government under Eric Pickles became the first department to advertise every single vacancy online. Still, far too many senior roles are only advertised internally. The proportion of appointments to the senior civil service from external applicants halved from 42 per cent in 2010 to 20 per cent in 2020.

From now on, ministers will have to personally approve any request to recruit into a senior civil service post without advertising externally. Importantly, this change will not remove any restrictions on the involvement of ministers in the appointment of individual civil servants, protecting the impartiality of the civil service. The changes will allow the many talented junior civil servants to rise through the ranks more quickly, will encourage gifted outsiders to join the service and, most importantly, will promote diversity at the top of the civil service.

During the pandemic, Whitehall became an adventure playground of talents, with data scientists, epidemiologists and software developers recruited en masse. Using expertise, wherever it can be found, is the route to a more efficient state. Clearly, that ideal is still some way off being realised. The cabinet secretary has himself admitted in a recent letter to The Times that many officials lack ‘technical and specialist knowledge’.

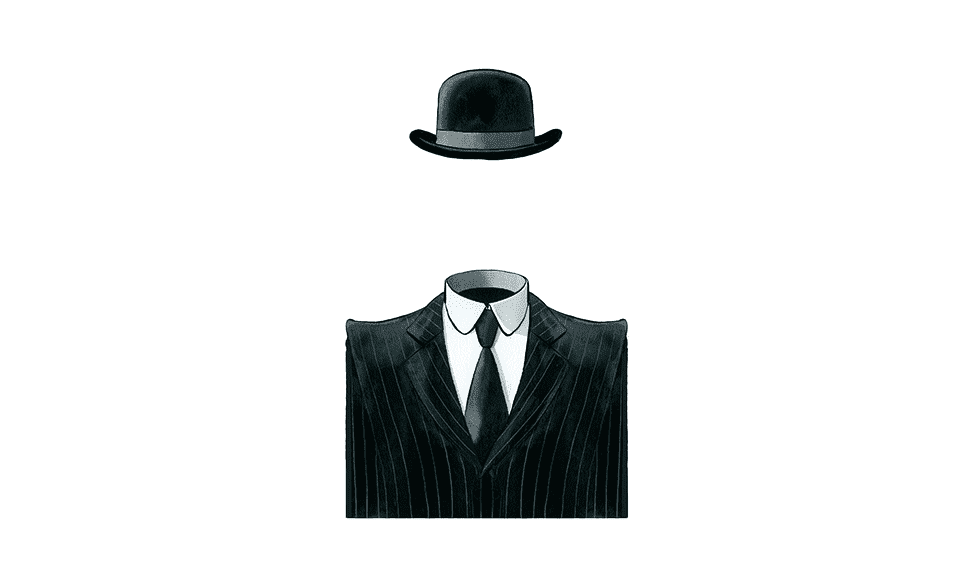

Much of the civil service is still a mystery, even to wonks like me who spend their days studying the machinery of government. Take, for example, the ‘Senior Leadership Committee of the Senior Civil Service’, which can authorise the appointment of candidates to the top 200 jobs in the civil service without competition. Quite what happens in this inner sanctum of inner sanctums is anyone’s guess. Very few details about the Senior Leadership Committee are publicly available. Its exact membership, terms of reference, rules of procedure, and the frequency with which it meets are unknown. No minutes of its deliberations have ever been published. It’s a black box that sits at the top of the British state.

It isn’t just Whitehall either. From January to April 2016, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy ran a call for evidence on closed recruitment practices in the wider public sector. Six years later, they have yet to respond to this call for evidence. Quite why ministers and civil servants should initiate and then abandon such an important call for evidence remains a mystery.

Trust in the civil service’s impartiality rests on its ability to implement the policies of election-winning governments. But the civil service can only deliver if it recruits the best, requires the best and promotes the best.

Comments