When to launch? For impresarios, this is the eternal dilemma. Autumn is so crowded with press nights that producers are heard to sigh, ‘The market’s full. There’s no room.’ When the glut abates in late November, the same producers sob, ‘The market’s empty. There’s no point.’ But national rags have to report on something, even a fringey foxhole like the Southwark Playhouse, and a bold investor can exploit this opportunity.

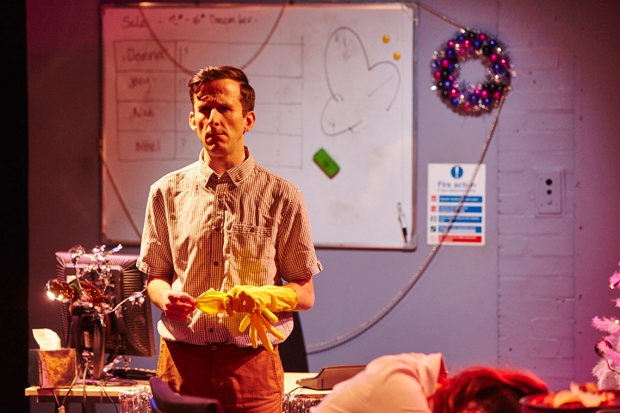

Most of the dailies sent their top sniffer dogs to check out Saxon Court by Daniel Andersen, which is set in the feverish, sharp-suited world of Square Mile recruitment. The play belongs to the long and noble tradition of the workplace revenge comedy and Andersen is doubtless settling a few scores by presenting encrypted portraits of former colleagues. His strip-lit kiosk of greed and fear is entirely believable. But is it likable? We meet Tash, a ditzy receptionist, with a blonde curly-wurly hairdo and a boob job that’s visible from Neptune. There’s shy, grumpy Natalie, who seems to be sitting on a secret. Is she pregnant? Joey, the kingpin recruiter, is being nagged by his wife to secure a pay rise, so he invents a fictional job offer to screw more dosh from the boss. A couple of bullied duds make up the numbers.

The pivotal figure is Donna, the founder of Saxon Court and its dictator for life. She holds Kipper-ish views on benefit scroungers and she likes to chivvy up her sales team with battlefield anecdotes. No earthling, she preaches, lacks a marketable talent. A candidate born minus arms or legs? Call every CEO in London and ask if they want a stamp-licker. Opinions like that make her pretty nasty but her malevolence isn’t sufficiently epic or magnificent to inspire our fascinated and semi-adoring revulsion. She’s just a gobby bigot who probably nurses some grave disappointment beneath her prickly rind. We don’t get to see it.

There’s not much inner life to any of these glib, bantering desperadoes. The show zings with energy and pace, and the cast perform with dash and vigour, but they can’t escape the ghost of Ricky Gervais whose diabolical account of nine-to-five drudgery has yet to be surpassed. There’s an out-of-date feel to Donna’s references to the Occupy crusties picketing St Paul’s. And the off-stage stuff about a kaput sewer and a blocked pipe vomiting faeces over the walls should have been cut. It’s not funny and it doesn’t move the plot anywhere useful. Now that Andersen has purged his system of these pirates he can move on to something better and grabbier. He’s not brilliant but he’s promising.

Simon Mason spent the 1990s dealing blizzards of coke to Britpop royalty and his drug-dusted memoir has now been transplanted on to the stage. Mason is a public-school drifter with a street hustler’s London accent, who slithers out of education and gets devoured by gear and music. Barely out of his teens, he rocks up in LA, dealing weed, graduating to crack, bankrupting his flatmate, then fleeing home to mum. ‘We both started crying, but for different reasons.’

This intriguing aside isn’t followed up and Mason’s reluctance to fill in the emotional details leaves his character incomplete. Purely by accident, he becomes the chief apothecary to a massive band, which he doesn’t name. But here’s a clue. Their tour bus broke down on a motorway near Carlisle and the two frontmen idled the time away flinging a Frisbee across six lanes of speeding traffic. Hence their nickname, ‘the Manchester City Frisbee Team’. He describes his astonished elation at seeing Oasis play live for the first time. And he confirms that Liam’s air of criminal menace, later derided as a marketing ploy, was entirely genuine.

Mason, who swiftly became hooked on heroin, offers a gripping analysis of the addict’s psyche as it yo-yos between despair and euphoria. He hits rehab and goes six weeks clean. ‘I’m normal!’ he cheers. And ‘normal’ for him means taking gear, which he duly does. Three months later, having relapsed and recovered, he straightens himself out again and celebrates his sobriety with a can of Special Brew. To celebrate the Special Brew he has a crack pipe. To celebrate the crack pipe he has a toot of heroin. Back to rehab. For Mason, the addict’s true compulsion centres on his ego rather than his fix. So only the truly narcissistic are at risk of full dependency. This useful insight explains why smack has failed to become a mainstream pastime (with barely 60,000 enthusiasts), even though it’s available everywhere and is very attractively priced.

Comments