This memoir is not a requiem for Tony Blair’s past, says Fraser Nelson. It’s a manifesto for his future — as a highly paid freelance statesman with no electorate to hold him back

Many prime ministers view their memoirs as their pension, but Tony Blair always had far greater ambitions. In the three years that it has taken him to write A Journey, he has become so wealthy that he does not need the royalties — and is giving them to charity. As his memoirs reveal, he has long thought it a shame great world leaders should have to retire. The example he cites is Condoleezza Rice. ‘She is a classic example of the absurdity of people with experience and capacity at the highest level not having big political jobs after retirement from office,’ he writes. ‘But that’s another story!’

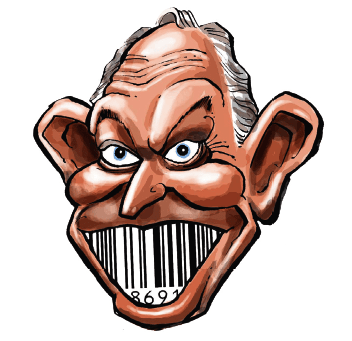

Indeed it is. And it is a story which Mr Blair has no intention of telling. It is a story about a prime minister who prepared for himself a political afterlife which has all the trappings of office but none of the traps. It is about how, aided by a toothy grin and a contacts book, he manages to have a staff of 130 and a turnover of an estimated £20 million. It is about how a former prime minister became a curious new political breed: a freelance statesman, available for hire by Arab governments or Western democracies. His memoir is simply the latest product from the very serious business of Blair Inc.

A Journey says what one would expect about his years in office. He speaks about ‘The West’ like a man who wishes to be its ambassador. A chapter is devoted to Northern Ireland, to underline Blair Inc’s credentials in conflict resolution. (Jonathan Powell, who has written his own book on the subject, works for one of Blair’s companies.) Another chapter, ‘Managing Crises’, is a suitable overture to the risk management industry. His declaration that he has ‘always been more interested in religion than politics’ is a nod to the Blair Faith Foundation. From cover to cover, the book carefully packages and polishes the Blair brand.

While Thatcher’s memoirs were an unapologetic defence and celebration of conservatism, Blair makes no such defence of Labour. One gets the sense of a political hermaphrodite, who has plenty of experience and opinions but has been left without a home since his party, New Labour, was destroyed. He praises the Lib-Con coalition, and denounces those who ‘lazily succumb to the idea that more state spending dressed up as fiscal stimulus is the sole answer’. He declares himself to be a ‘progressive’ — which is a notoriously catch-all label. Like Bill Clinton, he is something of an International Good Guy who carefully avoids any political cul-de-sac.

What he does with this new status is revealed in the postscript. ‘I begin as one type of leader — I end as another,’ he says. A leader? But surely this is the retired MP for Sedgefield? No, this is an entirely different beast: a statesman without a state. ‘I have never felt a greater sense of frustration, or indeed a greater urge to leadership,’ he adds. But whom would he lead? And to what purpose? He talks about his ‘world view’ — that ‘globalisation, enabled by technology and scientific advance, is creating an interdependent global community… The drivers behind this are not governments but people, and it is an unstoppable force.’ And what type of people? It is fairly clear what he thinks: that power is shifting to a new global elite which transcends nationality and government. And this is his new hunting ground.

He has arrived in this job by roughly the same means as he landed his last one: copying Bill Clinton. Blair’s memoirs reveal his infatuation with the American ex-president, and the pearls of wisdom about how spin is half of the political battle. Ten years ago, Blair looked on as Clinton left the White House, his reputation tarnished by a sex scandal, and went on to carve out for himself a new life. His new role involves the best bits of being a statesman — the red carpets, the presidential suites, the first-class travel — but with less of the irksome media scrutiny. The first step to achieving it was to renovate his image. Had Clinton limped off to Wall Street and written an embittered book replying to his army of devout critics, he would have come across as a loser — and his global currency would have fallen rapidly. Instead, he started on Aids charities, became known as a freelance statesman and even ended up helping to free hostages from North Korea last year. No small turnaround for a man once hounded in the White House by a special prosecutor for the lies he told about his affair with an intern. What Clinton managed to do was to combine Jimmy Carter’s post-presidential sanctimony with Henry Kissinger’s money-spinning advisory contracts.

Blair has now constructed a model even more advanced than Clinton’s. He has his own set of ‘halo’ companies: the Tony Blair Faith Foundation, the Tony Blair Sports Foundation, the Blair Africa Governance Initiative (based in America) and his position as an unpaid peace envoy to the Middle East. Blair’s genius was to make the book itself a ‘halo’ operation, by announcing he was donating the advance and the royalties to the Royal British Legion. It was an act of extraordinary generosity, which left even his enemies stumped for words. It removed any accusations that he was cashing in on his stories of war.

Blair’s gift for presentation has been seen every step of the way. He waited for months as speculation grew about him becoming president of the European Commission, and then ruled himself out at the eleventh hour — having milked every bit of free publicity. His book was launched on the day of a Middle East summit in Washington, so the cameras would snap Blair the statesman, busy in the pursuit of world peace. It is precisely the image he wants to covey.

What he is keen to cover up is how much money he’s making, and from whom. Very little information can be gleaned from his for-profit companies, which have names like Firerush Ventures and Windrush Ventures. There is no website for Tony Blair Associates, which offers ‘strategic advice’ for undisclosed fees. Richard Murphy, a tax specialist who has tried to get to the heart of it all, says the Blair companies are arranged in a way to minimise transparency. ‘The complex web of companies is not just designed to hide the money but also where it comes from,’ he says. ‘Blair doesn’t want anyone to know what he’s doing.’

One of the few sources is John Burton, Blair’s former agent, who recounted a conversation with his old boss. ‘I asked: “How many people do you employ?”, and he said 130. I mean it was 25 about two years ago and he said to me [then], “I have to earn £5 million a year to pay the wages.” So God knows what he has got to earn now to pay the wages.’ God may know, but Companies House does not. Only two of Blair’s companies filed accounts at its Cardiff headquarters, declaring a combined income of £11.7 million in 2008-09. Not long after leaving office, he drew a £2.5 million salary as an adviser to JP Morgan Chase and £2 million to advise Zurich Financial Services. Not bad for a prime minister who was notorious for his economic illiteracy.

In his memoir, he makes strikingly few claims to have acquired any economic insights since leaving office, save for mocking Labour’s spendthrift ways. There is no hint that, under his watch, a bubble was created by an avalanche of dangerously cheap credit. One assumes that these banks are not hiring Mr Blair for his financial acumen. What they are buying is a man with access to the world’s most powerful people. A man who, we learn from his memoirs, refers to Nelson Mandela as ‘Madiba& #8217; — his tribal name. Even Vladimir Putin, who has taken Russia so far back towards autocracy, is hailed for his ‘warmth’. Even Gandhi gets a posthumous mention.

Yet for all the abundance of money, there are few signs that Mr Blair is motivated by it. A man out to accumulate capital would not give so much of it away. More important to him is to have the apparatus of a world leader. I caught a glimpse of this earlier this year, recording a session of Radio 4’s Any Questions? A panellist had been rude about Mr Blair, suggesting he was being paid for his work in the Middle East. Minutes afterwards, the show’s producer received a furious phone call from a Blair aide and a demand for a retraction. It was not just the speed of the response that was impressive, but that the aide knew the mobile number to call. The ‘Excalibur’ model of spin, so devastating in Labour’s early years, is serving its old master.

And spin is what makes Blair Inc tick. His is an industry based on reputation management — a lost cause at home, perhaps, but certainly not abroad. It is as if he believes that boundaries, of party politics and nationality, are losing their power and he is rising above both. And that the princes of this new globalised universe will be those who acquire global reputations — by whatever means — and can move freely without having electorates to hold them back. Blair appears to regard Bono, the pop star turned aid worker, as a good example: ‘He could have been a president or a prime minister standing on his head.’ Bono may be Irish, but he is now a global citizen. As Blair aspires to be.

Indeed, Blair looks and sounds less British with each of his increasingly rare appearances in the country. The glottal stop which he would deploy on the campaign has vanished. In its place, a slight Atlantic twang. But Blair Inc aims to be as busy in the East as the West. ‘I now travel to China frequently,’ he says in his memoirs. ‘Its economic and political power, already vast, is a fraction of what it will become.’ And Blair Inc wants a slice of it. Not by accident does the Faith Foundation operate in 12 countries. It presents him as an unashamed believer (which works well in America), yet a respecter of Islam (which satisfies the Arab world). This is a version of a rather fuzzy faith designed to be as effective in Kuala Lumpur as it is in Kansas.

Just as Blair divined a gap in the market for British politics — and filled it with New Labour — it is as if he now sees a gap in world politics and wishes to fill it with Blair inc. ‘I enjoy my new life far better than my old one,’ he says. And this is the point of A Journey — No. 10 was, for him, only a staging post towards his final destination. His unwritten epilogue is that the world has not heard the last of Tony Blair.

Comments