On YouTube – and I urge you to look it up – there is a magnificent piece of footage from German TV, in which big band leader James Last leads his orchestra into a medley of hard rock hits, opening with Hawkwind’s deathless space-rock drone ‘Silver Machine’. And damn it if they don’t nail it. The members of the band with electric instruments play it just as Hawkwind did: the whooshing synth, the thudding bass, the fuzzing guitar. But instead of Lemmy growling out the topline melody, there is a huge rush of brass from the band, the brightness cutting unexpectedly through the murk. It is, unironically, brilliant. I have no desire to investigate much else of Last’s colossal oeuvre, but I can watch those few minutes over and over again.

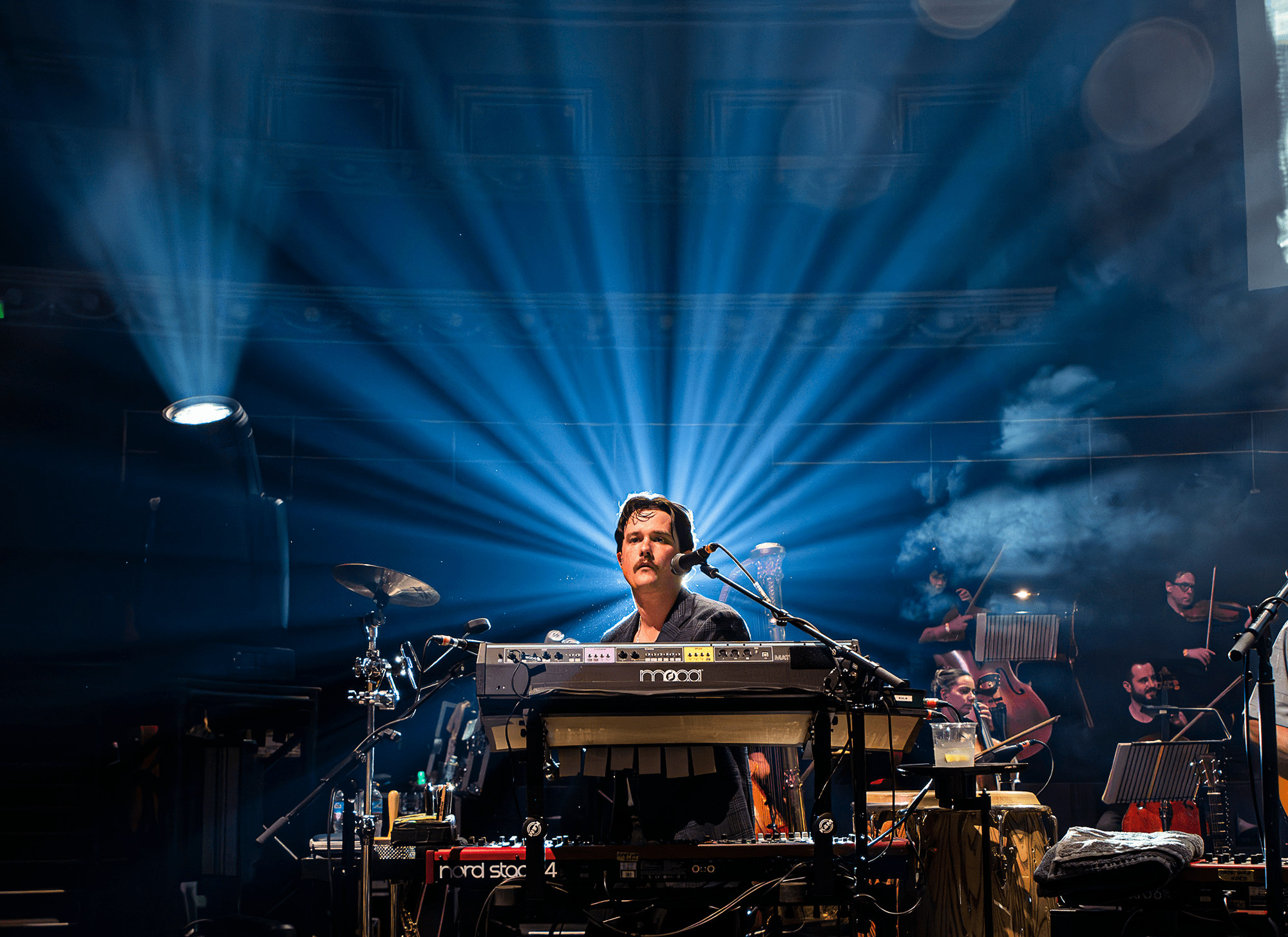

I tell you that because the clip captures almost exactly what seeing King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard perform with the 29-piece Covent Garden Sinfonia at the Albert Hall was like. Unexpected, silly, and thrilling.

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard are an atrociously named sextet from Melbourne, with whom I have not been keeping up since seeing them when they first came to London, 11 years ago. The reason I’ve not been keeping up with them is that to do so is a full-time job. Since then, they’ve released 22 more studio albums (taking them to 27 in total), comprised of any kind of music likely to have been played in the past by people who took drugs: space rock, prog rock, psychedelic rock, jamming, motorik, stoner metal, thrash metal, tropicalia. All that and more. They are psychedelic in the very broadest musical sense of the word.

They’re more or less a modern Grateful Dead, both in how they have built their own self-contained universe, and in their commitment to always changing. (Their two other nights had been rave sets at the Brixton Electric, which one attendee described to me as ‘intense. More like Throbbing Gristle than Pasha’.)

In truth, the first half of the show – a run-through, with orchestra, of their most recent album, Phantom Island – was pleasant but unexceptional. Phantom Island is at the sunniest, poppiest end of their work, and in the vastness of the Albert Hall, band and orchestra blurred into one another. It was like listening to Ike and Tina Turner’s ‘River Deep – Mountain High’, where there’s so much going on that you end up unable to hear almost anything.

And then the house lights came up, the band told us it was the interval, the orchestra went off, people went to get drinks, and the band stayed on, at first jamming formlessly before resolving into a motorik drone, which in turn segued into their metal anthem ‘Gaia’. It was extraordinary, not just for the playing, but for it turning a concert into a kind of happening. The orchestra returned, house lights went down, and the second half took flight with much heavier material: now the orchestra became a vast, elemental force behind the band, driving them forward, rather than swallowing them whole. After three hours I was exhausted and delighted.

I deleted the app that used to be called Twitter from my phone last week. I was fed up of opening it and seeing people talking about a world I don’t recognise. Particularly one in which inner London, where I live, and not in a posh bit, is routinely portrayed as a place where you can’t leave your house without being beheaded. The day I did that, I went to the pub just over the Holloway Road from me, which – for reasons I cannot fathom – was hosting a free gig by the Japanese group Super Jet Kinoko, their only UK stop on a European tour. Their bass player, Daoud Popal, used to be in the wonderful psych band Kikagaku Moyo (themselves collaborators with King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard), which made them an object of interest. Here was a very different kind of psychedelia.

There was mindbending drone, but also the hysteric rhythms of cheap dance music and sounds that fizzed like sherbert. They were absurd: a percussionist wore nothing but a jerkin, and a hat and underpants, from which protruded a giant phallic mushroom; a dancer in a head-to-toe alien costume raised an umbrella draped with foil streamers that doubled as a UFO. And a couple of hundred people – from people younger than my kids to people older than me, men and women, whose ancestries visibly lay in many different places – danced and laughed and left the pub beaming. And almost none of us were beheaded.

London has, indeed, fallen. Fallen under the spell of psychedelia. Tune in, turn on, drop out.

Comments