From bucket hats to Britney Spears, the 1990s and 2000s are back in vogue. Who could have predicted that the cringe-inducing baggy trousers and All Saints-esque crop tops that filled teenage wardrobes 20 years ago would be resurrected with such gusto by Gen Z? But there’s one part of turn-of-the-century culture that remains firmly consigned to the past. Unlike the clothing of the era, the romcom has proved remarkably resistant to modern reinvention – no matter how hard Hollywood tries.

Last month, two romantic comedy veterans – Reese Witherspoon and Ashton Kutcher – reunited in a stoic effort to woo audiences back to the genre. But their film – Your Place or Mine – was quickly panned by critics and has floundered at the box office despite its Valentine’s Day release. Likewise, Nancy Meyers – who directed The Holiday (2006) and What Women Want (2000) – has just had her latest romcom dropped by Netflix before it even reached production.

So why, despite a resurgence of other Nineties and Noughties trends, is the romcom failing? It is certainly difficult to believe that this small-c conservative film genre once had the cultural clout to turn the likes of George Clooney, Sandra Bullock and Julia Roberts into household names. Against a backdrop of gender fluidity, online dating and MeToo, the traditional boy-meets-girl formula suddenly looks outmoded. Are today’s audiences just too cynical for the kind of romantic idealism and economic aspiration that these films promote?

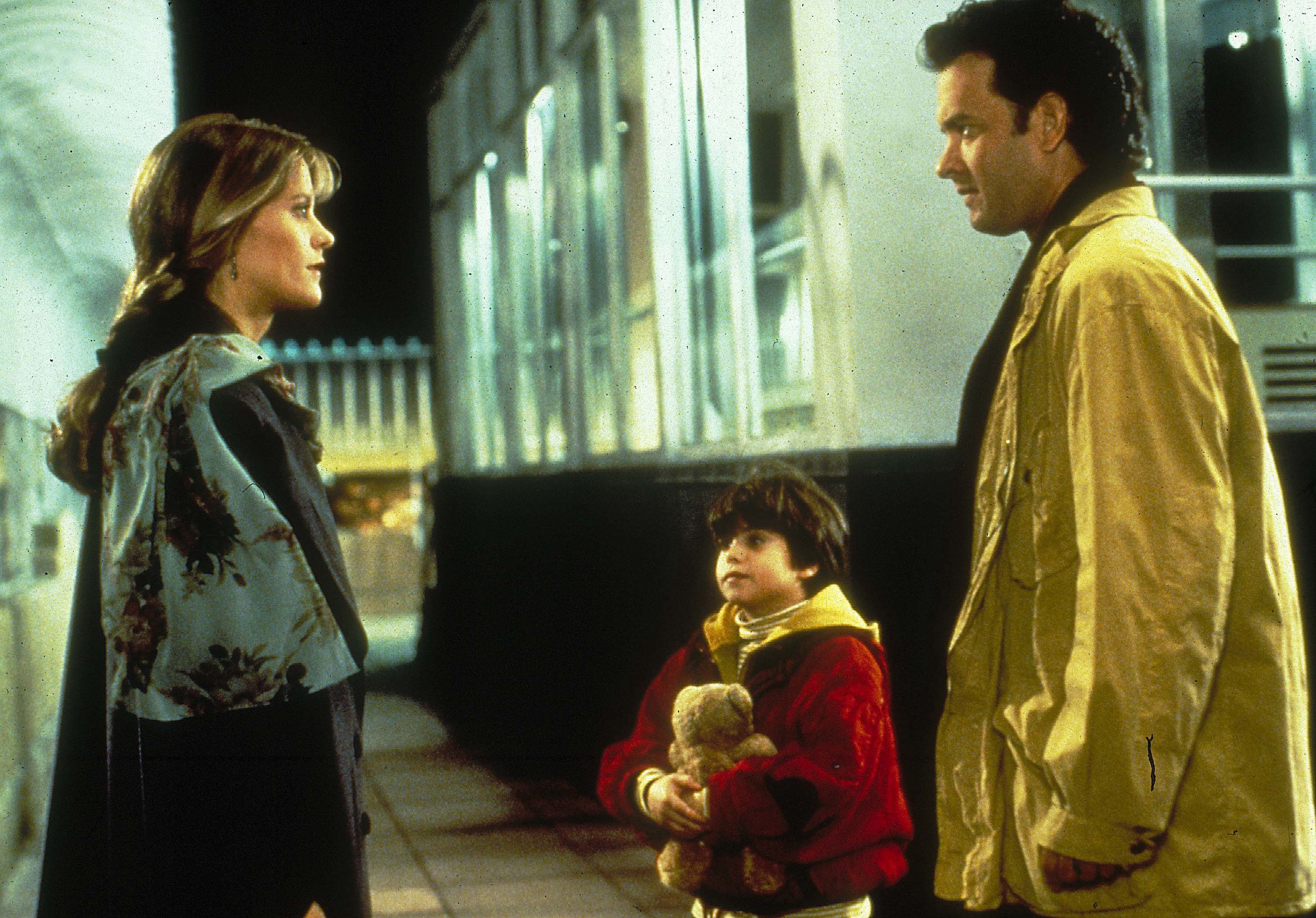

Before the advent of the internet, the idea of perfect strangers meeting by chance certainly held more mystique than it does in 2023; now, we have apps to do the hard work for us. Perhaps the modern dater – all too familiar with ghosting and two-timing – simply can’t stomach the doe-eyed optimism of lines like Sam’s in Sleepless in Seattle: ‘I knew it the very first time I touched her. It was like coming home… only to no home I’d ever known.’

The romcom’s plot devices of happenstance and fate don’t chime with modern experience. How can they when the phone in our pocket wants to make us masters of our own destiny?

Films such as Sleepless in Seattle (1993), Notting Hill (1999) and One Fine Day (1996) spoke to a world where these chance encounters seemed rare and special. They were also released at a time of growing economic prosperity, when the relatively affluent, urbanite lives displayed on screen felt almost within reach. The economic optimism of those years neatly translated into romantic optimism and filmmakers cashed in accordingly. It’s often said that the beating heart of every Nancy Meyers film is a beautiful kitchen – whether it’s Kate Winslet’s cottage kitchen in The Holiday or the gorgeous Californian ranch kitchen in The Parent Trap (1998). But this kind of aspirational domesticity is much less palatable in a cost-of-living crisis.

It’s understandable that Generation Rent – flat-sharing well into their thirties – can’t quite bring themselves to believe in the domestic utopias peddled by these films. Interestingly, this was a dilemma explored by recent British millennial romcom series The Flatshare (streaming on Paramount+), where two thirty-somethings struggle to form committed relationships against a backdrop of sky-high rents and constant bed-hopping between properties. It’s hardly the high romance we were given in The Notebook (2004).

And it’s not just the romcom kitchens that seem out of touch. Just think how many 1990s and 2000s romcoms use the office as a backdrop for their central premise: Hugh Grant’s high-rise office in Two Weeks Notice (2002), the newsroom in How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days (2003), the advertising agency in What Women Want, the two city slickers in One Fine Day and Tom Hanks’s picture-perfect architecture practice in Sleepless in Seattle. Even romcom stalwart Nancy Meyers relied on the office in 2015’s The Intern.

But in a post-pandemic world, the office is no longer the common denominator for audiences that it once was. And, as Your Place or Mine found out to its peril, it’s hard to conjure up chemistry when the two romantic leads mostly communicate via Facetime.

The high-school romcom is equally problematic. She’s All That (1999), 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), Never Been Kissed (1999) and Clueless (1995) all capitalised on the 1990s trend for high school movies. But this formula fails to stack up in an age where starring in a viral TikTok clip does more for your popularity than being Prom Queen. Filmmakers are constantly having to grapple with changing technology and its impact on dramatic tension.

As Sophie Hainey surmised in the New Yorker, this is not the first time artists have felt the clash of technological change. She argues that the landline gave literature a sense of ‘surprise, suspense and uncertainty’ and that its demise has created a problem for writers everywhere. How do you create tension when information is never withheld, when nobody has to wait for a call? The same is true of the communal spaces at the heart of the romcom – just like the landline, they create unpredictability. There are all manner of people to bump into at an office or a high school and a set of social codes that can be thrillingly contravened.

The smartphone may connect us more than ever, but it also makes life achingly predictable. Potential romantic connections are heavily vetted by algorithms before they even occur in real life. Packages can be tracked, locations shared. We are constantly aware of what is going on elsewhere. The fractured madness of Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once tapped into this idea beautifully. The romcom’s more linear plot devices of happenstance and fate don’t chime with modern experience in the same way. How can they when the phone in our pocket wants to make us masters of our own destiny?

Is it any wonder, then, that the makers of today’s romantic comedies are turning increasingly inward for inspiration? Nancy Meyers’s ill-fated romcom apparently centres around two filmmakers falling in and out of love as they make movies alongside each other. Its Hollywood setting betrays a crisis of confidence in the old romcom formulas; unlike offices, schools and kitchens, Hollywood hardly screams relatability. The best romcoms inject the magic of romance into an ordinary place: a bookshop in Notting Hill, the commute to work, listening to the radio in the car, the school prom.

If the romcom is going to make a comeback it must find a way to walk this tightrope between the magical and the ordinary. It must carve out some sort of moral core from the bearpit that is modern dating and work out what it is exactly that today’s audiences aspire to. Chances are it’s more than a glitzy kitchen.

Comments