The news that WHSmith is facing closure seemed inevitable. Good stationery may be one of the pleasures of life, but is anyone actually buying much any more? Of course, people will always need pens, string, bubble wrap and so on, yet the heyday of stationery has definitely passed. There was a time, when people still wrote letters to each other or used writing implements as a matter of course, that it was a large part of our shopping, especially if you were a school kid. We wrote in pen and ink (no biros), and for a child of the 1970s or 1980s, this usually meant the choice between a Sheaffer No Nonsense pen, chunky and with a screw-on top, or a Parker 25, stainless steel and, with its ‘stepped down’ barrel, faintly futuristic.

Ink for these – only blue, my school decreed – was provided for us in Bakelite inkwells sunk in our desks. The smell of ink, like that of chalk or fear, was a big part of schooldays back then – as were inky fingers, hand inspections, and sessions at the sink with soap and pumice stone. But later on in our teens, for letter writing at least, there were less sober colours available, like turquoise, violet or green (Parker provided them in their design-classic bottles, or there were brands like Pelikan or Waterman). Some people used a broad nib, giving a calligraphic, slightly voluptuous look to their writing, while others opted for a fine and spidery script. Both had their appeal – these days a 0.5mm Pilot Hi-Tecpoint (the king of disposable pens) makes a very good trouble-free stand-in for the second.

Then there were choices about letter paper. Did you go straight for Basildon Bond – ‘premium 90 gsm paper… allows the pen to glide effortlessly across the page’? Or perhaps the posher Three Candlesticks, who promise that their ‘“laid” writing paper gives an elegant touch,’ and whose tissue-lined envelopes add ‘understated sophistication’. Both these brands are still available and get their fair share of Amazon reviews, so someone, somewhere must be writing letters, and shelling out £1.65 for a first-class stamp. It’s reassuring they can still be bothered.

I thought about stationery a lot while growing up. Just as nothing was scruffier than a letter written on foolscap (over-folded into a wad, then stuffed unceremoniously into a too-small envelope), good writing paper was something you also noticed and, if it had a printed letterhead, seemed oddly enhancing to the sender. Expensive, personalised writing paper was one of those things adulthood seemed to hold out back then – a permanent address, a place in the world (even some able labels, perhaps, with your address on them, which you could stick over the envelope-flap like sealing wax). Adults seemed unassailable behind such things, the way they did in a good overcoat.

Assuming you moved on from writing pads, there were brands like Conqueror, whose ridged paper made a lovely scratching sound when your nib travelled over it, or Smythson (only for the most affluent types, who probably lived in mansion flats, in South Ken or Cadogan Square). With its bespoke service, you would get to choose fonts, paper colours (Smythson offer several shades of white and colours like ‘Park Lane Pink’ and ‘Bond Street Blue’) and double or single borders to the page. What people got at the end was a delightful artefact to send out to friends or colleagues that made their existence look, perhaps even feel, as solid as granite. It was and is ruinously expensive – 50 personalised sheets with envelopes from Smythson come in today at about £275, and there are other brands that charge significantly more. Who, in a world of texts or emails, would pay these prices?

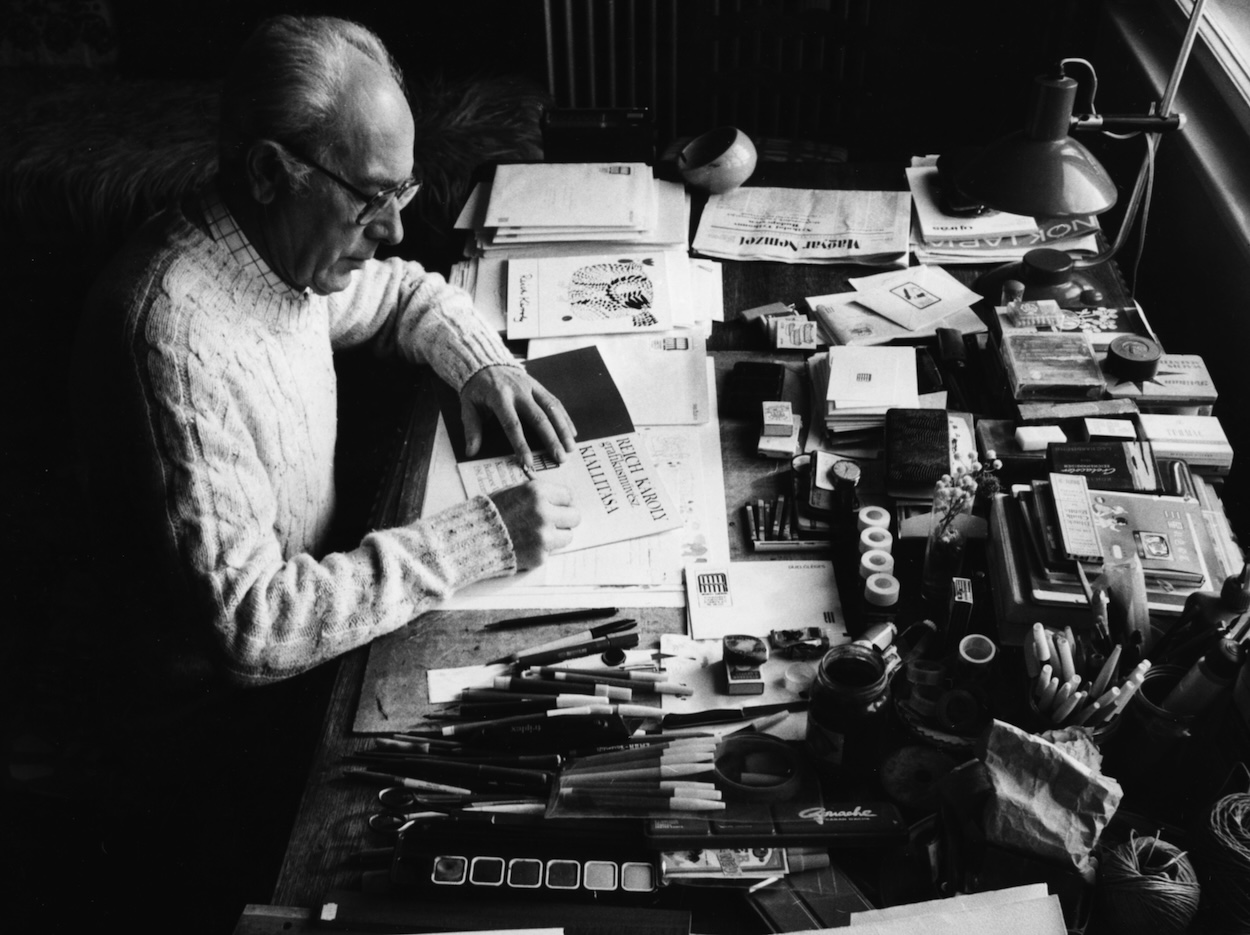

Then there was the question of notebooks – cloth-bound, spiral-bound, hard or soft-covered, lined or gridded. In my youth, as a would-be writer, these were desperately important. Friends who were published and earning a living from their pen could scribble on whatever they felt like. Those of us setting out needed all the morale-boosting we could get, and there were few things like a trip to Ryman’s to send a little bit of uplift into your day.

Muriel Spark refused to write her novels in anything but Bothwell spiral notebooks, sold only by James Thin of Edinburgh

Even working writers could develop fetishes here. Bruce Chatwin declared himself a devotee of the Moleskine, raving about their ‘squared’ pages, and ‘end-papers held in place with an elastic band,’ assuring us that he picked up ‘a fresh supply’ whenever in Paris (posthumously, he can perhaps take his sliver of the blame for Moleskine’s inflated prices and dreary ubiquity in 2025).

Muriel Spark refused to write her novels in anything but Bothwell spiral notebooks, sold only by James Thin of Edinburgh. So dependent was she on these that when the company discontinued them, Spark worried her creativity would grind to a halt – until the company agreed to make a special custom edition just for her. My own personal favourite – though I could live without it – is the A5 Europa Notemaker, with its lined ‘brushed vellum’ pages, spiral binding and solid cardboard covers. Is there a better all-rounder?

Notebooks will probably survive – they’re still in vogue – but will much else? I occasionally look back through letters I received 30 years ago – with their thick headed paper, fashionable postcodes and ‘071’ and ‘081’ London phone numbers. Like having the time to handwrite page after page, or even the readiness to exchange one’s inmost thoughts at all, such things seem to belong to the goodwill and spaciousness of a different age.

WHSmith may be on the way out then, but the world that underwrote it vanished decades ago. It’s all a crying shame – really good stationery was one of life’s delights. It could motivate, inspire and bring a touch of luxury into your day. Best of all, every penny spent on it was tax-deductible into the bargain – which was definitely worth writing home about.

Comments