Max Jeffery has narrated this article for you to listen to.

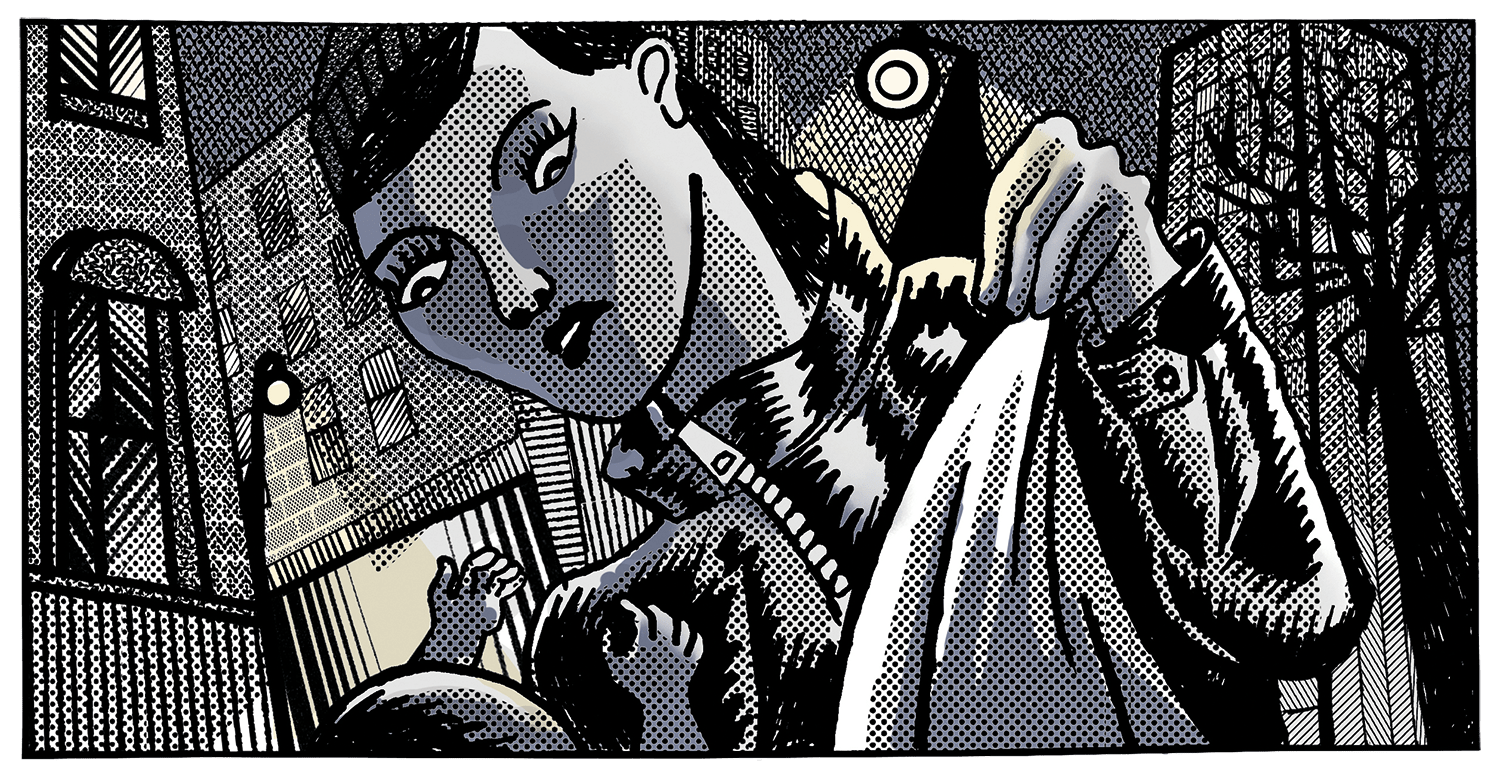

Elsa had been alive less than an hour and her umbilical cord was still attached when she was wrapped in a towel, put in a Boots shopping bag and left on the Greenway, a cycle path built on a Victorian sewage pipe that runs through east London. She was abandoned on 18 January 2024 by a rose shrub on the coldest night of the year.

She was not the first baby to be abandoned in that area of the Greenway near Plaistow. On 17 September 2017, a baby boy was discovered wrapped in a towel under a bush about a mile and a half from where Elsa was later found. The hospital called him Harry. Then, on 31 January 2019, someone found a newborn girl, also wrapped in a towel and put in a shopping bag. She was beside a park bench 500 yards from where Elsa would be left. It was cold that night too, and the woman who found her said frost had formed on her head. She was taken to hospital, where the staff named her Roman.

All three babies are black, and DNA tests showed that Elsa, Roman and Harry have the same parents. Last June at the East London Family Court, Judge Carol Atkinson let the DNA findings be reported for the first time. While Roman and Harry have been adopted, Elsa cannot be until the police investigation to find her parents is concluded. Judge Atkinson has been pushing officers hard to track them down.

In March I contacted Detective Inspector Jamie Humm from the Metropolitan Police, who leads the investigation. Humm has worked in the Met for 19 years, three of them focusing on child investigations. He told me there was no CCTV footage of Elsa’s abandonment, nor any witnesses.

Detectives always work from hypotheses, and for a while Humm’s was that Elsa’s mum didn’t want to be found. The evidence just pointed that way. Elsa and the other babies were left swaddled in public places, which seemed to indicate that whoever abandoned the children cared about them. The fact that they were found near to each other suggested she lived locally.

But this theory changed earlier this year. In January, Crimestoppers offered a £20,000 reward for information leading to the identification of the babies’ parents. Police also appealed for help from doctors and pharmacists who may have seen the pregnant mother. Crimestoppers got nothing. The police received only four calls.

‘Instead of having a leading hypothesis that mum will not come forward,’ Humm told his officers in a briefing afterwards, ‘my hypothesis now is that mum,’ he always calls her mum, ‘cannot come forward.’ It is possible that she is being held captive in the area.

Acting on this new hypothesis, police launched a manhunt last month after the National Crime Agency (NCA) drew a ‘GAI’, or ‘geographical area of interest’, looking at all the Greenway’s possible entry and exit points and marking a group of 400 homes where they thought whoever left the babies probably lived. The main road in the GAI was Lonsdale Avenue, a two-minute walk from where Elsa was found. ‘The answers are here,’ Humm’s superior, Detective Superintendent Lewis Basford, told me.

‘Instead of thinking that mum will not come forward, my hypothesis now is that mum cannot come forward’

Humm and his team are carrying out door-to-door inquiries. If the occupants are black, police policy is to ask them to do a swab test to check their DNA against that of the babies. The occupants can of course refuse to be tested – although that in itself may be revealing. It’s the job of Humm’s colleague Detective Sergeant Laurence Dight to ensure all 400 homes are visited by either the police or the NCA.

When I joined the team as they made their inquiries, Dight had four addresses on his list that hadn’t answered on previous visits. At each home, he knocked, stepped back, checked for any visible movement inside (‘you’re always double-guessing yourself,’ he told me) and then left if nobody came to the door. One of the four houses answered the knock, but only a decorator was in.

A local man approached us. ‘What’s this about, gentlemen?’ he said.

‘Abandoned babies,’ said Humm. ‘You lived here long?’

‘Long enough to know about it,’ replied the man.

‘I’m from the police. We’re still trying to find the babies’ mum.’

‘I think she’s long gone.’

‘You reckon?’

‘Yeah. It’s like trying to search for Maddie McCann, isn’t it?’

The investigation felt like a similarly unlikely exercise, and Humm, in his way, admitted as much. Knocking on doors and hoping to conduct swab tests, he told me, ‘are not efficient inquiries’.

Down Lonsdale Avenue I came across a couple called Derek and Tess, who have lived in the neighbourhood for 42 years. I asked them how they thought someone in their community could hide three pregnancies. ‘If someone was three doors away, we wouldn’t know their name,’ said Derek. Many people in the area don’t speak to each other, Derek and Tess said – not through a fear of discussing the babies (several residents hadn’t even heard about them), but just because this is how life is in some parts of the capital. Some parts of Britain.

‘We talk about communities, but actually they can be quite isolated,’ said Basford. ‘You get three or four houses and they’re very alike and very akin. Then you will find pockets where they will not know who is next to them.’

Officers don’t like to spend too much of their career in child investigations

The borough of Newham that the Greenway divides was once a favoured retreat of the gentry and wealthy merchants. The district of East Ham was studded with mansions; on the southern marshlands by the River Thames, villagers fattened cattle and reared horses. When the East End industrialised, the mansions were replaced with tenements. ‘[The] marvellous growth and development is absolutely without parallel in the history of the United Kingdom,’ wrote one historian of the East End in 1908. Since then many English families have moved out and many other nationalities have moved in. It is not a particularly social area.

I asked Dight how working in child investigations affected him. Seeing death and gore didn’t linger, he said – before joining the team in 2023, he was in the murder unit for five years – it was thinking about what a child had gone through that made the mind whirr. ‘How many times can you keep going back to that?’ he wondered. He’s a father of two, and he said it wasn’t surprising that officers don’t like to spend too much of their career on child investigations.

The DNA results will take several weeks to come back. There will be many, but even then there might not be a match. When I spoke to Humm, he kept bringing up a case of child abandonment from 1998 in Cheshire. A baby boy’s body was left in a bin bag near Gulliver’s World theme park, and it took 25 years to find the mother. Perhaps, Humm was suggesting, the police in this case will be spending many years on the Greenway.

Comments