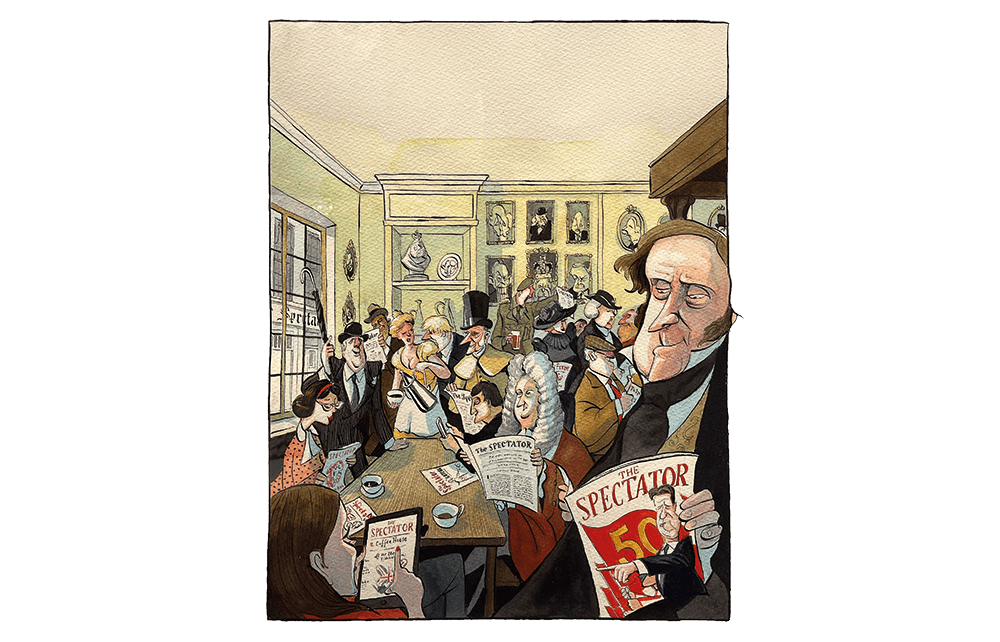

What explains The Spectator’s unprecedented success? No weekly in the world has matched its longevity: 196 years and 10,200 issues. In my history of The Spectator, 10,000 Not Out, I talk about the battles that shaped the magazine. It has long been a voice for classic liberal values and in its best moments, kept doing so even when support for those causes was unpopular. But when we look at its history, we see its best moments – and its shakier ones.

The founding spirit of The Spectator was a humble-born Scotsman, whose energy and principle took London’s media class by storm. Robert Rintoul’s career south of the border began with the weekly newspaper The Atlas, but after two years he left in protest at owners who sought to ‘vulgarise and betwaddle’ the title. Instead his new venture was funded by a circle of Radical friends, including Joseph Hume, the indefatigable Aberdeenshire MP, and the Hon. Douglas Kinnaird, banker and intimate friend of Byron.

As a Sunday paper, The Spectator sought to scrutinise the previous week’s events

The first issue of this ‘weekly journal of news, politics, and literature’ emerged on 6 July 1828. As a Sunday paper it sought to scrutinise the previous week’s events under the weighty name of The Spectator: there was no denying Rintoul’s ambition to follow in the footsteps of Joseph Addison’s and Richard Steele’s transformative title of the same name (1711-12), which so rapidly came to dominate political and cultural conversation under Queen Anne. The (new) Spectator’s very first sentence still cleaves to an essential truth: ‘The principal object of a newspaper is to convey intelligence.’ As Rintoul announced to his friend, the publisher William Blackwood: ‘We have begun The Spectator on the neutral ground in politics, but decided in its criticisms.’

It began as a ‘strictly independent paper’ and ‘the organ of no party’ but was unrelenting in its campaign for democracy what went on to be the Great Reform Act. This seemed to scare off some of Rintoul’s backers (at the time, the word ‘democrat’ was as shocking to some as ‘Communist’ came to be in McCarthyite America). Within five years, Rintoul purchased complete ownership of the paper for himself. Freer than ever to run The Spectator as he liked, Rintoul continued to lead on many issues of the day.

Fraser Nelson, the current editor, has spoken of what happened next. ‘Rintoul established an important principle. The Spectator is not (and never has been) a proxit-maximising publication. We believe in diversity of opinion, in liberty – and the best writing. If we can bring the money and readers to where the journalism is, then: great. But we will never bend The Spectator to go where we think money might be.’ This approach brought clout.

In a leading article of 1837, the paper revealed both wonder and surprise at its influence through its independence:

A journal, published but once a week – debarred by its price and the nature of its contents from circulation amongst the millions – never under the obligation of patronage from any government, nor at any time the organ of a party or sect, but always representing the individual opinions of its editor and sole proprietor, – a paper thus inherently destitute of the means by which influential journals commonly acquire their power, is just now the observed of all observers.

Rintoul steered the ship for 30 years before disembarking just before his death in 1858. By this point The Spectator’s reputation was assured. As Walter Bagehot remarked when editing the Economist: ‘I go round to The Spectator office to know what is going to happen.’ Plus ca change.

But although the paper’s reputation was secure, its future was not. And the three-year period after Rintoul retired was an abject mess. After a brief and lamentable spell under a clueless Shropshire nail magnate, the paper was secretly acquired by a brace of Americans, who sought to peddle favourable information about President James Buchanan Jr (in office 1857-61). As one of them confided to his diary before the purchase, Americans in Britain were:

unrepresented at the fountain head of civilisation, Christianity, and commerce, while all other nations have their organs. We are abused without the means of defence, and misrepresented without the power of corrections… An organ under proper control would be invaluable to an American Minister here, and I would sooner be its editor than Envoy to the Court of St. James.

Under this sorry period of pay-to-play propaganda, The Spectator churned out a steady stream of uncannily favourable trans-Atlantic coverage, much to the bemusement of long-standing readers. Even Napoleon III seems to have paid for positive coverage of French affairs. The owners James McHenry and Benjamin Moran sought to cover their tracks by falsely announcing the slippery editor – Thornton Hunt, son of the celebrated essayist Leigh – as the proprietor. But suspicious hacks and confused subscribers knew something was afoot; readers dropped off in droves, and fell below 2,000 for the first time since its earliest years.

The magazine, now so patently corrupted from its founding vision, was reduced almost to nothing; as a rival title later observed, ‘the best newspaper doctors would have pronounced it beyond hope of restoration to health and strength’.

Yet things can change just as rapidly for the better. In 1861, Meredith Townsend – a brave and ingenious journalist who had earned his stripes in India – and Richard Holt Hutton – a Yorkshireman of uncommon intellectual range and depth – joined forces as owner-editors. As their first meeting came to an end, Townsend called after Hutton: ‘I say, have you got any money?’ For such a man on such a mission, the answer of ‘Not much’ was good enough. And so began, as a staff member recalled, four decades of co-rule by ‘two of the cleverest men in England, and two of the most refined gentlemen in the world’. Townsend’s portrait hangs in the editor’s office to this day.

With full freedom, the new owners could stake their claim by following their own principles to support – contrary to almost every single title in Britain – the Union cause in the American Civil War. Although backing the North had negative consequences for the English economy, The Spectator put principle before comfort. The correctness of their conviction was, in the longer term, not just demonstrated but worn as a proud emblem of their editorship, as adverts during their tenure repeatedly declared:

The proprietors, who in 1861 purchased The Spectator, have since that date conducted it themselves. They are therefore exempted from many influences which press severely on the independence of journalism, and have from the first made it their chief object to say out what they believe to be truth in theology, politics, and social questions, irrespective not only of opposition from without, but of the opinion of their own supporters.

Then comes the star piece of evidence:

Their object is to reflect the opinion of cultivated Liberals, but in the matter of the American War they fought against the mass of the very class they are trying to represent, and were finally acknowledged by them to have been in the right.

As owners of the magazine, Townsend and Hutton could shape it totally in their image. As the long-term staffer, and future prime minister, H.H. Asquith later recalled, The Spectator ‘was written almost from cover to cover by the two proprietors’.

As the readership steadily grew, it was fortunate in taking on and shaping a wealthy successor as editor-owner, John St Loe Strachey, who became the proprietor in 1897. Again, his independence was a blessing: he had the freedom to pursue causes with conviction, even if an unpopular policy had the risk of leading to financial ruin. As the owner of the Daily Mail, the future Viscount Northcliffe, observed at the time: ‘It would not matter to Strachey if Mrs. Strachey were his only reader. He would go on sticking to his Free Trade policy in The Spectator as strongly as ever.’

For his part, Strachey declared his steadfast commitment to that economic principle in a letter to Winston Churchill, stating that he was ‘prepared to fight this thing out even if it ruins The Spectator. It won’t of course do that but it may cost me half my readers, and I am quite prepared to see it do so’. For his part, Churchill was convinced: ‘The Spectator will be on the winning side as well as on the right side.’ All the while, Spectator readers took heart that the magazine would fight hard when it felt it had to.

Readership grew to new and impressive heights over the quarter-century of Strachey’s term, although the post-war depressions of the 1920s required some renewed declarations of purpose. In 1922, Strachey reminded his readers about the paper’s editorial independence:

The views expressed by us, whether right or wrong in themselves, are not the resultants of external and undisclosed influences – official or financial, political or propagandist. Not only does no commercial magnate, but also no ministry, no party leader, and no social ‘movement’ or ‘organisation’ play the part of the predominant partner in our columns.

Tensions naturally emerged, though, when Strachey’s successor as owner tried to have a hand on the paper’s activity. The editor, Jack Atkins, complained about the clumsy operations of Evelyn Wrench (again, by chance, in a letter to Churchill): ‘I am going to give up editing The Spectator shortly as I find my relations with the new principal proprietor impossible. He continually wants to interfere and he is very ignorant.’

When Atkins did indeed step down, Wrench followed the Spectator tradition of editing the very magazine whose bills he paid. Led by its principles, The Spectator continued to grow. When its first centenary came around in 1928, then prime minister Stanley Baldwin told the nation by radio how the paper’s convictions make it such a success:

We admire The Spectator because it has always stuck to its principles. We may not like them at times, but it has stuck to its principles, regardless of circulation, of profit, or of any other consideration. It will sink or swim with its principles.

Rather more happy was the choice of Evelyn Wrench to partner with Angus Watson and to appoint a new editor, Wilson Harris. These two proprietors maintained indirect control of the magazine for forty years, but soon learned that editorial independence allowed the magazine to thrive best.

In 1954, The Spectator was acquired by the urbane but ambitious Ian Gilmour, who realised after five years in harness that the task of editor was too onerous for his plans. But he struggled to give sufficient freedom to his replacement, Brian Inglis: in 1961 he fired off an absurdly long letter to the editor, outlining how the magazine had drifted from its core ethos, becoming ‘completely divorced from the political life of the country’. It was no surprise that the letter’s recipient soon left, nor that its author soon became MP for Norfolk.

The appointment of Iain Macleod as editor (1963-5) was the first in a series of figures whose lives at The Spectator intersected with parliament, most notably with the editorships of Nigel Lawson (1966-70) and Boris Johnson (1999-2005). Despite some visionary editors, The Spectator was nearly brought to its knees by Gilmour’s successor as proprietor, Harry Creighton. After acquiring the title in 1967, and dissolving the very trust that existed to ‘eliminate as far as reasonably possible questions of personal ambition or commercial profit’ in an owner, Creighton cut costs at every corner, eventually making himself nominal editor so as to save on wages.

The Spectator still has many a battle to fight

The magazine in turn became a scrappy affair, both in content and in form. It was losing £1 million a year as the readership fell rapidly – so sharply, in fact, that Creighton sought to hide the fact by removing The Spectator from the Audit Bureau of Circulations. Somewhat ironically, the magazine was saved only by the European Common Market, since its vehement protests against joining Europe guaranteed a devoted readership across the political spectrum.

In 1975, a new owner arrived with fresh confidence and energy. And, after nearly 150 years of existence, the businessman Henry Keswick was the first Spectator owner who did not have a spell at being editor. Instead, he instantly employed the only journalist he knew, the young and brilliant Alexander Chancellor.

As the latter told readers with tongue lodged in cheek:

There are mysteries which no wise man should probe, and the motives of Spectator proprietors are one such mystery. What matters to The Spectator’s journalists is not only that they should enjoy the security which, in present circumstances, only a rich proprietor can give them, but that they should be required to offer nothing in exchange other than the best of their abilities and their own honest judgment of what is interesting, entertaining or true.

The Spectator was further revitalised in the hands of Algy Cluff (1981-5), a true and devoted lover of the magazine. However, in the late 1980s the train nearly went off the rails after acquisition by the Australian-based John Fairfax Ltd: while the Australian conglomerate could very helpfully pay off an overdraft of £300,000 it simply could not understand the title or its audience. Without Charles Moore in the driving seat, things could have ended in disaster.

In 1990, Fairfax went bust – but eighteen months earlier the magazine had found a new owner, the Canadian mogul Conrad Black, who incorporated it into the newly formed Telegraph Media Group. Although Black would occasionally flex his proprietorial muscles – notoriously via long letters printed without comment on The Spectator’s correspondence pages – he was for the most part a benevolent patron.

Yet some constraints were evidently palpable: as Charles Moore observed on leaving his post: ‘This ownership has been beneficial to The Spectator in every respect except one: it has been awkward when we have wanted to write about the affairs of the Daily Telegraph or the Sunday Telegraph.’

In 2004, the paper was acquired by the Barclay brothers, David and Frederick. Twins of ten children to Scottish parents, these ‘working-class Tories’ made their own fortune through confectionery, property, hotelry, shipping, and – like Rintoul – the press. Crucially, they trusted the magazine to operate under its own steam and on its own terms: with Andrew Neil appointed as chair in 2004, and Fraser Nelson as editor in 2009, The Spectator’s readership has grown to reach new heights and global range with the digital world.

The launch of Coffee House, of SpectatorTV, and the increase in Spectator events has forged a more tightly-connected community of Spectator supporters.

And now The Spectator welcomes its fourteenth proprietor, Sir Paul Marshall, who takes up a title with not just a proud history but a promising future to defend. For, as it nears its 200th year of unbroken circulation, The Spectator still has many a battle to fight. There is no shortage of issues to take on: the hollowing out of community; the emptiness and timidity of the institutions; the vacuous slogans and self-contradictory shibboleths of popular culture; the blithe onward march of artificial intelligence; and the continual yearning for deeper spiritual meaning.

The Spectator has thrived under proprietors who both know what needs to be done – and picking those best able to do it. Long may that continue.

Proprietors of The Spectator:

- Robert Rintoul (1828-58)

- John Addyes Scott (1858)

- James McHenry and Benjamin Moran (1869-61)

- Meredith Townsend and Richard Holt Hutton (1861-97)

- St Loe Strachey (1897-1924)

- Evelyn Wrench and Angus Watson (1925-54)

- Ian Gilmour (1954-67)

- Harry Creighton (1967-75)

- Henry Keswick (1975-81)

- Algy Cluff (1981-5)

- John Fairfax Ltd (1985-8)

- Conrad Black (1988-2004)

- David and Frederick Barclay (2004-24)

- Sir Paul Marshall (2024-)

Comments