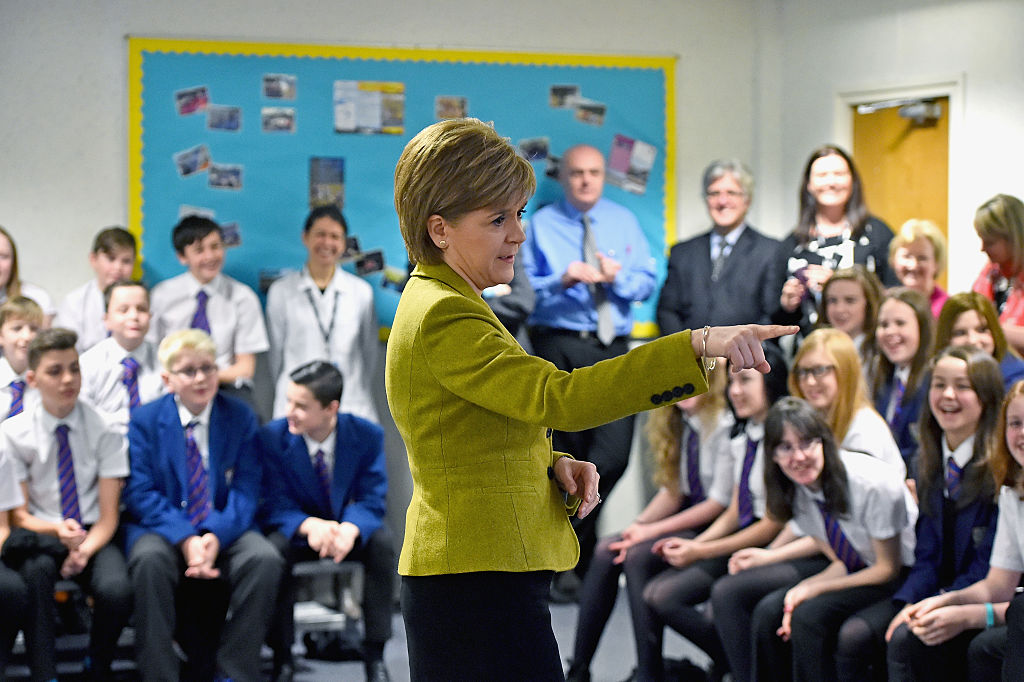

I am afraid that whenever a politician asks to be judged on their record, it is sensible to assume this reflects a confidence they won’t be. At the very least such promises are hostages to future headlines. Take, for instance, Nicola Sturgeon’s boast that education – and specifically closing the gap between the best and worst schools in Scotland – is her top priority. Judge me on this, she said. Well, OK.

Today the SNP government published the results of the latest Scottish Survey of Literacy and Numeracy and, as has become annually predictable, they make for depressing reading. While standards of reading have remained relatively constant amongst both primary and secondary pupils, there has been a sharp decline in writing ability. This follows last year’s survey which reported declining standards in numeracy.

According to the SSLN, 85 per cent of P4 pupils from affluent postcodes read well; just 67 per cent of those from poorer neighbourhoods do so. Notably, however, since 2012 there has been a Scotland-wide decline in the percentage of children performing well and the rate of decline is the same across all social categories.

By the second year of secondary school just 42 per cent of boys are performing well in writing. Although girls outperform boys at every stage, even in Scotland’s most affluent areas just 59 per cent of S2 pupils are meeting expected levels of attainment. In more deprived neighbourhoods – defined as the poorest 30 percent of data zones – most children fail to reach those targets with just 40 per cent ‘performing well, very well, or beyond the level’ expected.

Again, the pattern is clear and, according to the government’s own analysis, ‘statistically significant’. The results in 2014 were worse than the results in 2012 and the results in 2016 were worse than the results in 2014. As for ‘listening and talking’, again, only one in two Scottish S2 pupils is deemed to be performing well though at least here there was little statistical difference between the results obtained in 2016 and those reported four years ago.

Now, a generous soul might conclude that this just goes to show that Nicola Sturgeon is right to make education her ‘top priority’. And it is true that she has, unlike her predecessor, at least identified the problem. Ms Sturgeon makes a virtue of her concern but this takes some chutzpah, given that her party has been in power for a decade now. Still, a problem identified may be worth a tiny cheer. Alas, the SNP’s policy proposals in response to this evident record of underachievement are, if we are kind, muddled.

On the one hand, the Scottish government wishes to divert £120m each year directly to headteachers to be spent on narrowing the attainment gap between the performance obtained by pupils in affluent areas and those from poorer neighbourhoods. On the face of it, this is an endorsement of the principle that schools should enjoy much greater autonomy. But if a little autonomy – and given the strings attached it is likely to be smaller than the headlines might lead you to believe – is a good thing then wouldn’t more autonomy be even better? Shouldn’t headteachers, for instance, be able to hire their own staff, rather than accepting, as is often the case, whatever teachers they are given by their local authority?

Then again, the government also proposes creating new ‘education regions’ that would largely render the role of local government education departments redundant. How this is squared with a commitment to local accountability and how, indeed, these ‘regions’ would work remains unexplained. What is evident, judged on the responses to the government’s own school governance consultation, is that no one outside the government welcomes these proposals. And for good reason since they must amount to increased centralisation.

So, in one area the government boasts of decentralising education while in another it plans to further centralise it. In the same manner, it proposes scrapping the surveys of numeracy and literacy that now embarrass the Scottish government on an annual basis, replacing them with standardised tests that, to placate the teaching unions, may not be all that standardised at all and certainly should not be used to condemn school performance. Though, the first minister insists, we need this data so that school and pupil performance may be more accurately measured. If you’re confused by this, you too can work in the education department.

Sturgeon complains that the SSLN is just a survey but it seems worth noting that her government’s own statisticians think it sufficiently rigorous to be worth reporting. Moreover, it is consistent with other findings, not the least of which are the international PISA tests in which Scottish performance has declined, at least in relative terms, since 2000. The most recent PISA results were the worst ever recorded and a jaundiced observer might conclude this helps explain why the Scottish government has withdrawn Scottish pupils from two other surveys of international educational attainment.

Ms Sturgeon boasts that record numbers of pupils are now passing exams and going on to ‘positive destinations’. The rigour of those exams is questionable however; my impression is that academics at Scotland’s ancient universities tend to the view that today’s students are less well-equipped for university academics than were their counterparts a decade ago. Meanwhile, ‘positive destinations’ essentially means ‘anything but prison’. Like any politicians, Sturgeon takes the credit for good outcomes while denying responsibility for bad ones. In each instance, she would be better served by taking a more restrained, modest, approach.

Of course many pupils do fine but there is a consensus, shared at the highest levels of government too, that too many do not. On the one hand ministers must boast about record levels of attainment while, on the other, insisting that the status quo is not good enough and change cannot be avoided. The insistence on that latter point leads one to think assertions of educational excellence may well be exaggerated.

Not all of this is the SNP’s fault. I have little confidence very much would be different if Labour and the Liberal Democrats had remained in power in Edinburgh since 2007. They, like every other party, endorsed the new Curriculum for Excellence which, amongst other things, was designed to promote inter-disciplinary, skills-based, learning. It is not clear that CoE has been a glorious success.

Nor, however, is it accurate to argue that the SNP has ‘done nothing’ on education. On the contrary, it is possible it has done too much. That is, that the decline in performance as measured by the SSLN and PISA surveys does not reflect a lack of government interference but, rather, a surfeit of it. Teachers are forever being bombarded with new initiatives and are, in the experience of those I speak to anyway, endlessly plagued by the introduction of fresh and often baffling new guidelines notionally – but only notionally – supposed to help them achieve this or that new goal or target.

Data, of course, can be measured and it is in the nature of government that what can be measured must be what is valuable. Sometimes this is the case but not always. Equally, because the government can change systems it is tempting to suppose that if the system is tinkered with, good results will follow. Sometimes, too, this is doubtless the case but more often life is more complicated than that.

Which is to say that I have little confidence that any of Scotland’s political parties actually have the ability to transform the country’s education system. It is true that the status quo – the McBlob, if we are to put it in Govian terms – remains opposed to real reform but it is also true that none of the parties yet have a clear, far less a coherent, plan for that reform. (The Tories have done more work on this than some but even Tory politicians privately admit they have much more for to do yet.)

It is, in the end, the culture stupid. And, for all the obvious reasons, changing that is not something government finds easy to do.

Comments