THE WAR AND THE CIVIL SERVICE.

[To the Editor of The Spectator]

SIR,—May I suggest that some of the normal public services may, for the time, be curtailed in order to give patriotic young men the opportunity of serving their country in another way? The number of deliveries of letters might be reduced without serious inconvenience; a possible curtailment may be suggested in many other directions. Service with the colours is the one thing that matters now, and it should be made plain in every town and village how greatly those who are debarred from it honour and appreciate those who accept it. Everywhere the families of those who have relatives in any branch of the Service should be marked out for special consideration and special distinction. Of course we must see that none of them suffer from the absence of the breadwinner; but much more than this is required, and we have to create a definite public opinion in regard to the position. There are probably many ways of doing this, but I would suggest that in every town and parish meeting-place a roll of honour should be preserved of those who have come forward to serve their country in its life struggle, and that they should, as a matter of course, be given priority of claim to civil appointments after the war is over.—I am, Sir, &c., W. A. BAILWARD. [We fully agree with all our correspondent’s suggestions.— ED. Spectator.]THE VOLUNTARY SYSTEM [To the Editor of The Spectator]

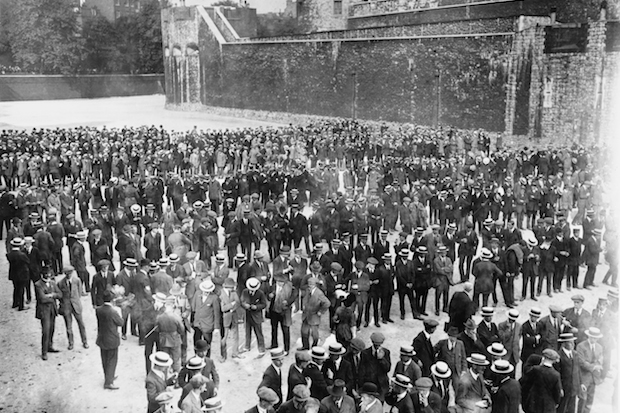

SIR,—The voluntary system is not having a fair trial. The Government should make the nation understand that Germany is striking at us through France; that we are her objective. The expression “helping France” is misleading and unfair. The healthy young men of the well-to-do classes who are staying at home to earn money and play golf whilst their neighbours sacrifice business, and perhaps life, on their behalf, should be told that they must pay for such substitutes, and that this will be the first war tax. Eligible men of the working class should be told that, if unemployed, they will not receive relief unless they have volunteered now, and that they will not be engaged on any public works such as are contemplated to relieve distress.—I am, Sir, &c., W. A. SMITHE Blackbush Cottage, Denham, Bucks.HOWLERS

[To the Editor of The Spectator]

Sir—Everybody knows the description of the first sea fight between Romans and Carthaginians, and how Duilius flung overboard the fowls which had offered bad omens, saying as he did so: “If they won’t eat, they may drink, anyhow ” (biberent salient). A “sweet girl” undergraduate once put “let them drink salt water” on her paper for biberent saltem. I was the examiner, and it may amuse you to be told that I gave her full marks, in spite of her “howler.” The rest of the paper was of quite unusual merit. The “howler” was obviously the merest blip.—I am, Sir, &c., Ex-SCHOLAR TRIN. COLL, DUB.[To the Editor of The Spectator]

SIR,—I gather with regret from Dr. Rendall’s letter that the camp at Tidworth for public schools in the Southern Command—and for Eton and Harrow—was to be open also to old boys between seventeen and thirty. Are not these the very men Kitchener wants? Would not each one of them bring in others (we are a deferential nation, as Bagehot said) by his example ? Of course the public schools camp is pleasanter —is it more useful? Are we to say of this development of the public-school spirit—falsely here, I think, so called—as Robin Hood said of his broken bow,” Our bane thou art, our boot when thou should’st be.” The freedom of Europe, the existence of the Empire are at stake. Is it a time for soft billets, or billets that non-public-school men are likely to think soft, or for pressing social distinctions P—I am, Sir, &c, J. SENIOR Salisbury

Comments