In 1982, Pope John Paul II surprised a few people by beatifying Fra Angelico, the 15th-century Dominican friar from near Fiesole. It’s not clear why he put Beato Angelico on the road to sainthood, given that the artist didn’t perform any miracles. And yet, after spending a few hours immersed in his works, which are both profoundly sacred but also staggeringly beautiful, you begin to understand the decision.

He was certainly a hit with popes. Pius XII was such a fan that, in 1955, when the first major Fra Angelico exhibition was held at the Vatican, to mark 500 years since his death, he gave a handwritten speech praising the painter as ‘a genius’ who ‘preached with his brush’, and whose mystical visions ‘transcend the heights of the human to open like a glimmer of light into the heavens’.

Fra Angelico was certainly a hit with popes

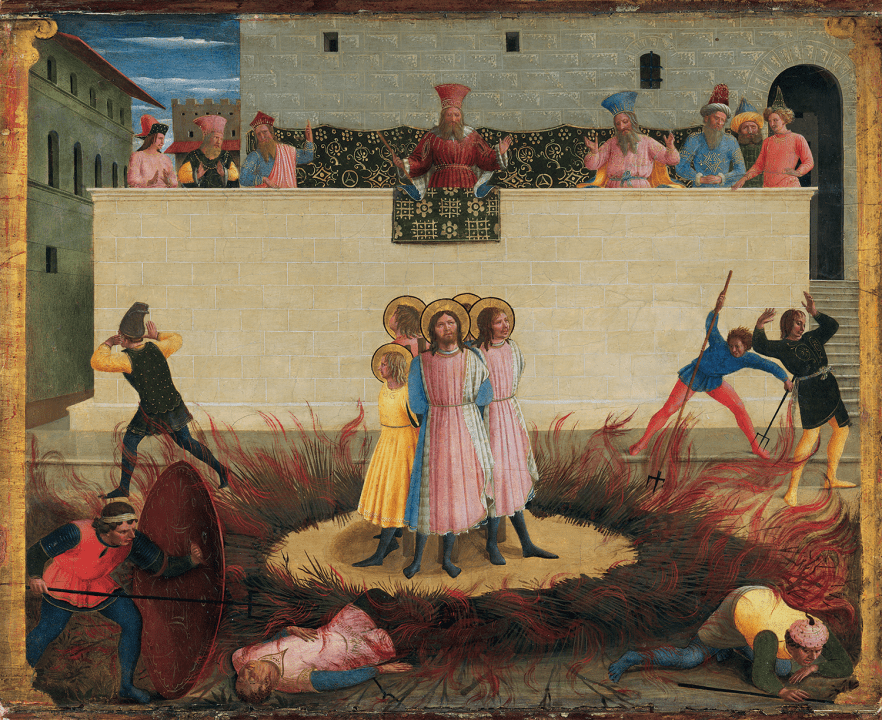

This new exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence has been four years in the making and is a major departure for a gallery that usually hosts blockbusters by Jeff Koons, Marina Abramovic and Tracey Emin. The eight rooms take you more or less chronologically through Fra Angelico’s life, which began in the hills north of Florence in 1395 and ended in Rome in 1455, where he worked on commissions for Pope Nicholas V. In his early life Angelico studied as a miniaturist, and he excels at cramming in masses of detail into every available inch. He also had an eye for the sumptuous (he never scrimps on the gold leaf), and this eye-wateringly gorgeous quality is always muscling in on the piety.

As a young man Angelico joined the Dominican order and received commissions for altarpieces and reliquary tabernacles. In one, depicting the coronation of the Virgin from the early 1430s, the face of St Dominic turns from a large crowd to meet our gaze directly, a figure who would make frequent appearances throughout his work. He also contributed frescos to a new Dominican monastery – now the Museo di San Marco – commissioned in 1437 by Cosimo de’ Medici. They appear in the monk’s cells, including one of the Annunciation that hits you just as you reach the top of the stairs (see below).

So central was San Marco to Fra Angelico’s life and work that the exhibition is a joint venture between the museum there and the Strozzi. But while San Marco has opening hours typical of a state-run Italian museum (8.15 a.m.-1.50 p.m., various Mondays excepted), the Strozzi is open seven days a week, 10 a.m.-8 p.m., and until 11 p.m. on Thursdays. This means that if you time your visit to the Strozzi well, you can drink in Fra Angelico’s works practically alone in silent contemplation, which they demand. Not that you need to be devout to appreciate the quality of Angelico’s craft. There is something so kind and gentle in the faces he paints, their expressions full of pain or wonder.

You can drink in Fra Angelico’s works practically alone in silent contemplation, which they demand

This show is also a wonder of logistics: more than 140 works have been amassed from 70 different lenders from across the world. Of these, 28 have been specially restored for the exhibition, including one from the Ashmolean. Curator Carl Brandon Strehlke had to exercise considerable charm to persuade galleries, churches and a few private collectors to lend some very fragile items. The current Duke of Bavaria called a family meeting after Strehlke turned up begging for a work they had vowed never to lend. They took a vote and he was lucky. Others held fast: the National Gallery owns two parts of the San Domenico altarpiece but their answer was no.

One of the most astonishing achievements is to have reunited 17 of the 18 components that make up the San Marco Altarpiece, which was dismantled in the 1700s. There is much talk of predellas – the base of an altar that is typically made up of several painted panels. These have suffered the most over the years, frequently chopped up and sold off individually. Two panels turned up in a Dorset house-auction in 2007, part of the estate of an Oxford librarian whose father had bought them for £200 in California in the 1960s. They fetched £1.7 million and are now back at San Marco. Others have flown in from Washington, Minneapolis, Munich, Altenburg, Venice, Dublin and Paris. They are displayed together in what curators call an ‘exploded reconstruction’ (an unfortunate term), so that we see the whole as it might once have been. The result is quite moving, not least as it may never happen again. As reunions go, this one is not to be missed.

Comments