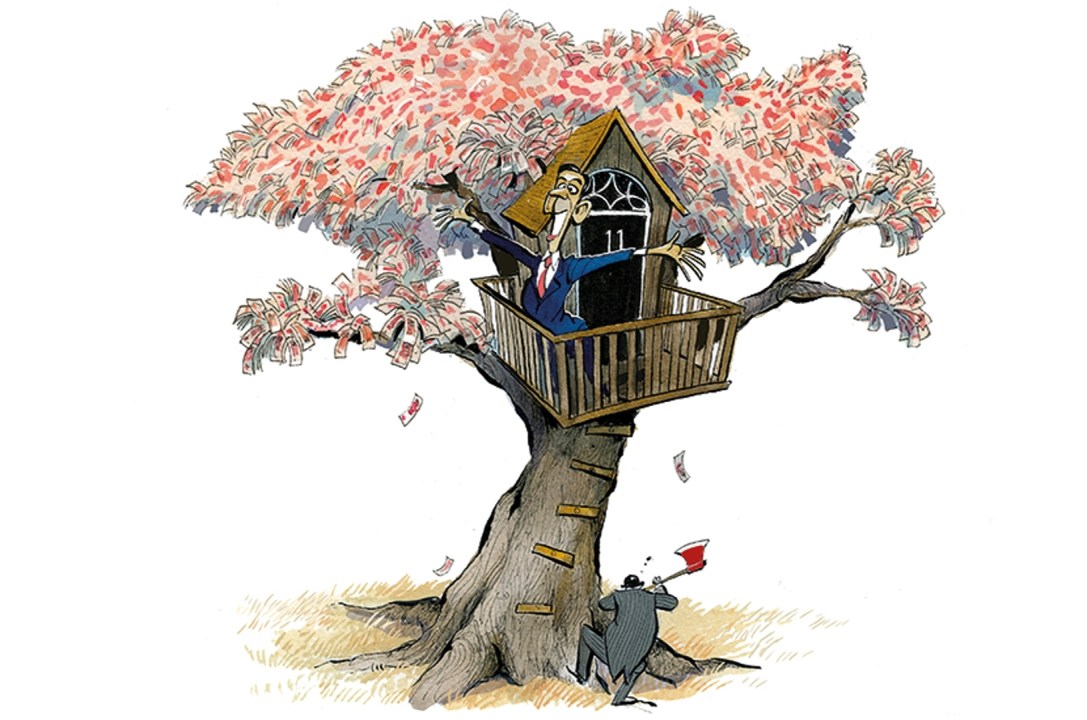

Rishi Sunak’s tax hikes pack a punch: by 2025, over £19bn is estimated to be raised from the freeze to the personal tax threshold, and a staggering £50bn from a new, tiered corporation tax structure. That’s a lot of people out of pocket, and businesses diverting their profits away from workers and consumers and towards the state.

Criticisms of the cash grab are splashed across the front pages of the papers today. Across the pond, the Wall Street Journal has lambasted Sunak’s policies:

‘Britain’s political class, and especially the governing Conservative party, prides itself on fiscal rectitude. So Mr. Sunak already faces pressure to “pay for” all this relief. We sympathise, but in this instance he would have been better off waiting.’

Economic heavyweights have been asking questions about inflation

For a Chancellor with a reputation for promoting fiscal responsibility and sound finances, no doubt Britain’s £2.8 trillion pile of debt sits uncomfortably with him. But tackling the debt, balancing the books, was not the top priority for Sunak going into this Budget. As I say in this week’s magazine, the Chancellor had a far more immediate concern driving his agenda: that the extremely agreeable conditions that exist now for borrowing vast sums of money might start to change. Even if rates remain at historic lows, any uptick could leave the UK in a perilous financial situation.

Until mere months ago, it seemed the economic consensus was that easy borrowing was here to stay. Governments want to spend and markets are ready to lend: why question it? But recently, economic heavyweights have been asking questions about inflation: not necessarily predicting its resurrection, but pondering what might trigger its rise. A major concern is that America’s new President, Joe Biden, is pushing ahead with a £1.4 trillion ($1.9 trillion) stimulus package, which will land just as America’s economy is reopening its doors. Many of the conditions that have kept inflation suppressed in the past have changed, or completely disappeared. If inflation started to creep, many of the levers central banks might use to get it under control have already been pulled.

It’s not something Sunak talks about much in public, but there was passing reference to this at the Budget: ‘while our borrowing costs are affordable right now, interest rates and inflation may not stay low for ever,’ he said, noting that this small rise in rates could lead to a fiscal hole of £25bn.

Some think the Chancellor is being too cautious, and that his tax hikes will do more harm than good, especially when the UK’s growth rate – forecast at seven per cent – looks to be spectacular next year as the UK economy bounces back from the crisis. But from 2023 onwards the Office for Budget Responsibility suggests we’re back to business as usual, with growth rates averaging a lacklustre 1.6 per cent. Higher taxes are only going to weigh down the possibility of more impressive figures. Innovative solutions and policies will be needed to give the UK the boost it deserves.

Comments