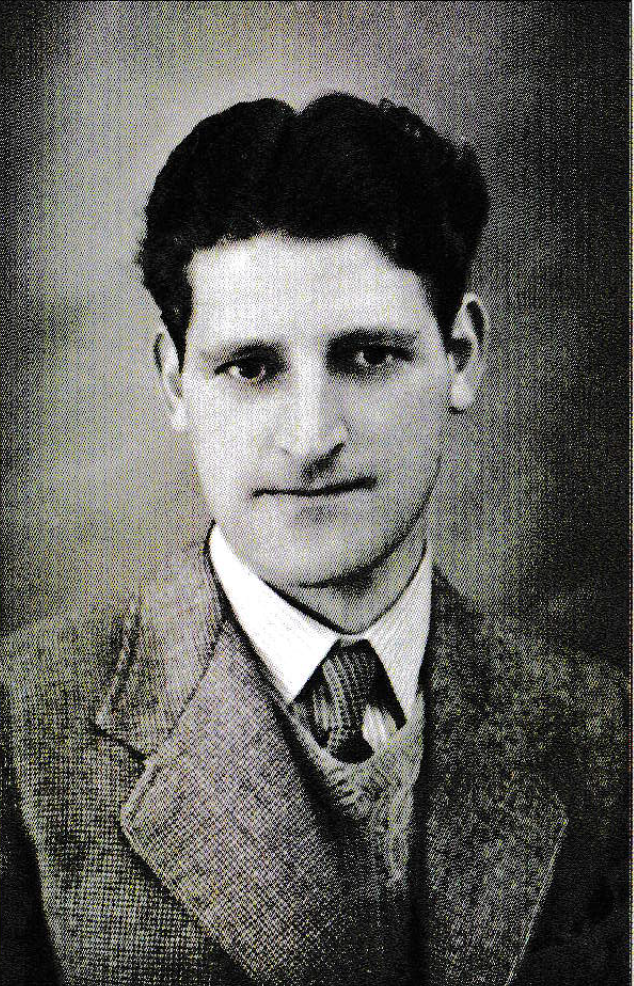

On a grey January morning, at a small, sparsely attended ceremony in a chapel in North London, we said goodbye to my granddad, one more statistic in this vile pandemic. Jack Brown grew up in poverty in Ipswich and performed heroically in the Navy during world war two; twice-sunk, once by an enemy torpedo, once by a collision with an Allied boat (the family joke is that Uncle Albert from Only Fools was based on his experiences). He went on to father six children, and had a 40-year career as a station-master. As granddad’s coffin was wheeled in, draped in a Navy flag, it was hard to dismiss the thought that Covid-19 had done what the Nazis had failed to do: see him off.

Except it’s not that simple. Granddad was 97, and had been in hospital for weeks following a fall at the flat where he had lived alone since the death of his beloved wife in 2008. His mind was still razor-sharp – he was forever firing off letters to the newspapers, military historians, and his many friends – but his physical health was failing, and I’m not sure he’d have reached his century (a shame, as I’d love to have seen the reaction of this affirmed Stalinist to a letter from the Queen). Jack’s death is of course sad for the family, but the true tragedy is the way in which the pandemic has affected the manner in which we said goodbye.

Jack’s oldest child – my mother – has Alzheimer’s and lives in Yorkshire, which meant I was unable to see her at Christmas. But when her dad died I drove north to give her the bad news in person; she was devastated. Mum had her run-ins with her father, but her remaining memories are fond ones – one small positive of her condition. After discussing with the family, we agreed it would be irresponsible and impractical for me to drive up again and bring mum back for the funeral – she’d have to share a car with me, stay at my home with my wife and kids, and no doubt forget about social distancing at the ceremony itself, risking not only her own health but those of her loved ones. Instead mum watched the service on a live feed with her carer, who told me later the video kept buffering; an image I sense will remain with me for a long time.

Jack’s son Liam – after whom I was given my middle name – died three years before his father and another daughter was stranded in Spain, unable to come home due to the latest restrictions. Even so, due to current funeral guidelines, which state a maximum attendance of 30, I was unable to bring my wife and children. Jack had children, grand-children, great-grand-children and he was well-liked and retained contact with colleagues from the railways, Navy mates, and political comrades, many of whom called him simply ‘The Master’.

Politics were important to the Browns. In the Fifties, because of his British Rail position, granddad even took his wife – my Irish nan Kit – to Moscow, where his Communist beliefs saw them treated well. There, they disgraced themselves somewhat: descending the sweeping staircase at a grand ball, my nan muttered that Jack’s flies were undone. ‘That’s nothing,’ he growled. ‘Your dress is tucked in yer knickers.’

It was over politics that granddad and my mum fought so violently – whereas he was a Stalinist, she was a Trot. Granddad – a little over five feet tall but pugilistic in look and manner – was unrepentant about his admiration for ‘strong men’ like Stalin and Milosevic. A few years ago he chuckled to me: ‘The rest of the leaders are playing draughts. Putin’s playing chess.’ I once amazed Francis Wheen, who wrote a glorious biography of Marx, when I admitted that I was almost named after Marx – my parents compromised on Mark.

Despite his dogmatic politics, my granddad was in many ways extraordinary, blessed with an unfaltering memory and a love of poetry and classical music. The last time I saw him he quoted Shakespeare at length in a Suffolk burr undiluted by seven decades in the Smoke before showing me some of his correspondence (including a kind note from Peter Hitchens, hardly a political bed-fellow). When he called to wish me a Merry Christmas, he said he was looking forward to seeing me and the kids again very soon. Now we never will; frustratingly, we have yet to say a proper goodbye. But we will. People like my granddad beat the Nazis – and we can beat this too.

Stalin once said: ‘If only one man dies… that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.’ To date 90,000 people in the UK alone have died whilst infected with Covid-19. It’s a staggering amount – so let’s not forget that behind every statistic there is a tragedy, a story, a life well-lived and then extinguished.