From time to time newspapers invite writers to describe the ‘books that changed my life’. The resulting columns too often dazzle the reader with a display of erudition or passion, rather than tell the more mundane truth. The mundane truth is that our dispositions and the courses of our lives tend to be fixed before our ages run to two digits: a time when we were unlikely to be tackling Proust, understanding Nietzsche or appreciating C.P. Cavafy. The child being father to the man, we should be looking at fairy tales, picture books and First Readers if we seek the truly formative influence of literature. Foreign and war correspondents or derring-do travel writers are less likely to have been set upon their life’s path by Wilfred Thesiger, T.E. Lawrence or Eric Newby than by Enid Blyton’s Five Get into Trouble.

From almost the moment I could I read voraciously: everything, anything I could get my hands on. Then, at around 14, I stopped (I don’t know why) and never properly resumed the habit. My real literary influences, therefore, come from the early years and pre-adolescence, all seen and read through the eyes of a child.

Two books made me the Conservative I was to became, one at the age of about six, and the other as a nine-year-old.

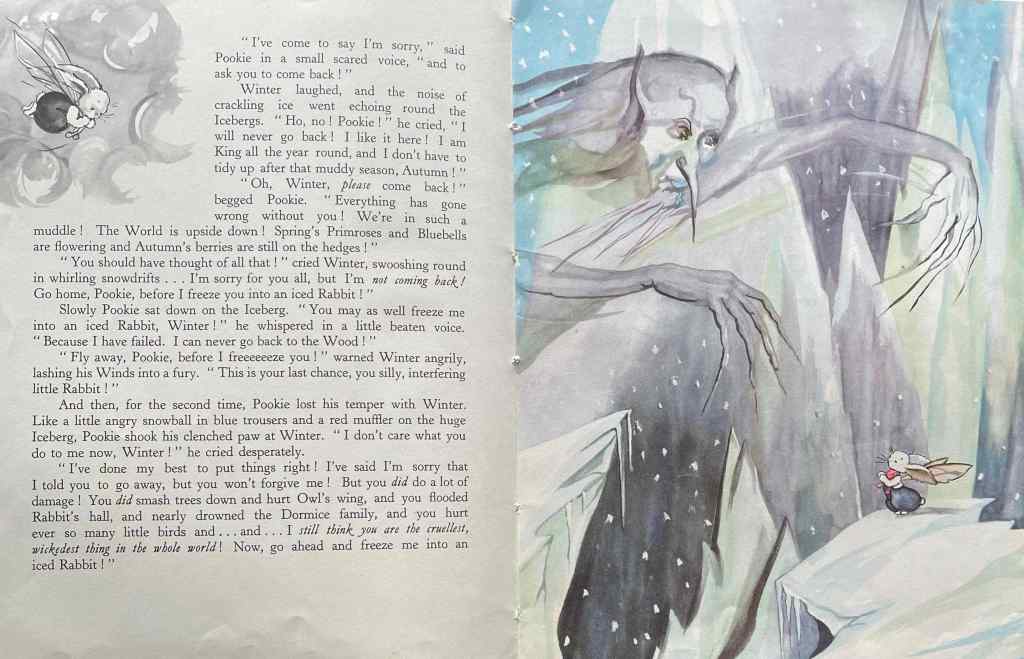

Pookie Puts the World Right by Ivy Wallace, first published in 1945, was my favourite book at the age of about six. It’s one of a series of Pookie books, all sensationally illustrated with vivid, whole-page colour pictures: a series largely forgotten now. Pookie was a winged rabbit, cared for by Belinda, a ragged girl who lived alone in a cosy cabin house in a forest. That’s the reason, incidentally, why my youngest sister, Belinda, bears the name: Mum asked for suggestions.

Pookie, sleeping in his tiny bed made by Belinda from a shoebox, is awoken by his protectress. A terrible late-autumn storm has brought down trees and flooded ditches. The pair rush out at first light and rescue sodden and now homeless little animals and birds, dry and feed them, and tuck them up by the fireside to keep warm. Another storm comes. Furious at the cruelty of nature, Pookie rushes out and rages against the storm (it takes the form of the Giant, Winter) for being so cruel and laying waste to lives and habitats. Affronted, Winter departs, vowing never to return. Pookie is lionised by the woodland folk who gather to praise him.

Then it all goes wrong. Winter doesn’t return. Flowers are unsure whether to blossom, trees confused about shedding leaves. Birds wonder when to nest, and small mammals who’d been looking forward to hibernation grow uneasy in the unseasonably mild weather. Without the scouring effect of winter, stream beds become clogged and dead foliage is left on trees, leaving no space for the new. The woodland folk all turn on Pookie, blaming him.

Embarrassed and guilt-ridden, Pookie makes an epic flight to the North Pole, Winter’s home, to beg him to come back. The tiny figure of an exhausted rabbit on a snowy glacier is confronted by the Giant Winter. The full-page illustration – Winter a fearsome, ice-faced giant with frozen fingers and icicles hanging from his nose – was so scary to me that I kept it under my pillow to take out and look at in the night until fear drove me back under the bed covers.

Winter explains to the chastened Pookie how nature needs seasons, how the old must be replaced, and everything stripped and cleansed for renewal. And – this harsh lesson I took to heart – how it was only the lazy animals who burrowed in places that flood, or nested on branches that were rotten, or stored no nuts for winter, who fell foul of the storm. Prudent creatures made provision. Prodigal creatures had been taught a lesson. Winter takes Pookie in his cupped, icy hands and flies him back safely to the forest and to Belinda, before beginning his cruel but necessary work.

Did this story teach me the Tory fundamentals? Or did it simply trigger in me an understanding that was already there? Impossible to say, but in the life of the little boy I was, my mother and father were my moon and sun, and my effervescent mother, warm and loving, would hear no ill of anyone and taught me that everything is beautiful and everyone is good, and all you need is love. My father, a quiet man, taught me (by example; he never moralised) the importance of reason and scepticism. And in this war of outlooks I always hesitated, nagged by the suspicion that there was something dishonest in Mum’s outlook yet loving her best. Pookie Puts the World Right tipped me Dad’s way, and there I remain with an irreducible core of slightly harsh conservatism.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm confirmed it. I was about nine, and lonely in a one-term summer school in the Vumba mountains in (then) Rhodesia. Vumba Heights had only one bookshelf, and I read everything on it, including this small novel that seemed to be about animals – and I loved animals. Knowing nothing about communism, or Stalin, Lenin or Trotsky, I wouldn’t even have known what the word ‘allegory’ meant.

But almost from the first chapter I could see the revolution wasn’t going to work. The animals couldn’t possibly all be equal. Discipline and organisation was called for. There needed to be incentives: carrot and stick. Somebody had to get a grip, so I supported the pigs from the start. Only later, looking back, did it become clear to me that my Toryism, if not born from a boyhood reading of Animal Farm, was confirmed in the imagination of a nine-year-old.

There has been a steady stream of learned and densely written books about the meaning of conservatism. They leave one none the wiser. Should you, for your Christmas reading, wish to bone up on this still-mysterious political force, let me suggest two sessions of extremely easy reading: Animal Farm and Pookie Puts the World Right.

Comments