You might (if you’re over a certain age) still think it pretty amazing that TV not only allows you to watch Mario Götze put in that amazing goal, live, as it happened, in Rio de Janeiro’s Estádio Maracanã, but also that you can witness so immediately and tangibly the passion, the drama of that moment — you on your sofa in twilit Surrey, Somerset or deepest Sutherland watching those emotions fleeting across the individual faces of traumatised Argentinians as they come to terms with bitter defeat.

The impact of that extraordinary connection across the continents is nothing, though, when compared to the intimacy and immediacy of radio; the way a single voice can invade your thinking mind, take over your thoughts, make you believe that you are listening to someone who is talking just to you, no one else, from wherever they might happen to be. This week we heard from two such voices, vivid, visceral, demanding attention, their connection with the listener instantaneous and startling.

In The Weekend Documentary on the World Service, Satish Kumar asked us to relive with him the pilgrimage he took 50 years ago from New Delhi to Washington DC via Moscow, Paris and London on a mission to bring about nuclear disarmament. He and a friend (Prabhakar Menon) were inspired by hearing about the mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, who at the age of 90 was arrested and jailed for one week after taking part in an anti-nuclear protest in south London. This was 1962, just before the Cuban missile crisis, and the Russians were experimenting with above-ground nuclear bombs while the Americans were building up their own nuclear arsenal against Moscow. ‘We must do something,’ Kumar thought.

He and Menon decided to visit the capitals of the four nuclear powers on a peace pilgrimage, delivering their personal message to the four premiers. But how to ensure they made an impact? We must go on foot, said Kumar, ‘then it will be a human story’. They carried with them no money, no food, nothing to help them on their way. Wars begin and end in fear, Kumar explained, ‘but peace begins with trust’. If we have no money, we will have to trust in God, in the people we meet, in the universe, in ourselves.

On 1 June 1962 he (and Menon) stood at the grave of Gandhi in New Delhi at the beginning of the journey. Two years (and 8,000 miles) later he was standing beside the grave of President Kennedy, too late to deliver his packet of peace tea to that president. ‘There was neither peace nor war but something beyond — a moment of complete stillness. Gandhi and Kennedy. Kennedy and Gandhi…From a grave to a grave. To make the point that if you trust in the gun, a gun does not always kill a bad person. A gun can also kill a Gandhi. A gun can also kill a Kennedy.’

Powerful stuff, spoken with such passion, as if Kumar was still that young man who had crossed the Himalayas, peak by peak, negotiated the Khyber Pass, plodded through Afghanistan (‘one of the most beautiful and peaceful countries…the people with great innocence living close to nature, close to the land’), drunk tea with the Shah of Iran and Nikita Khrushchev and been thrown in jail by de Gaulle.

In Homage to Caledonia this week on Radio 3, A.L. Kennedy confessed to being a Scot abroad in ‘an interesting year for Scotland’, one of many writers coming out of the woodwork to try to work out what Scotland means to them before the vote in September changes it irrevocably, for good or bad. She’s unusual in being a novelist, inured to days and weeks of solitary confinement while working on a book, who’s not afraid of taking to the public stage as a stand-up comedian. She knows how to work the mike, drawing us in with compelling changes of pace, light and dark, sometimes upbeat, at others morose. But she also has the writer’s eye for detail and absurdity.

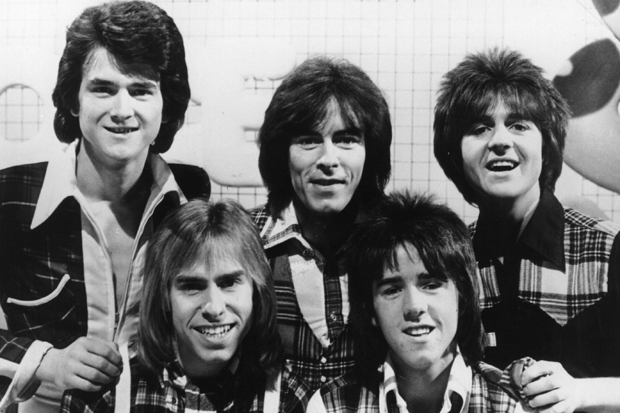

Her five short essays gave us the kilt (her own Kennedy tartan being ‘a vile combination of puce and acid yellow’), the Bay City Rollers (‘the sort of music one might expect to hear in an upbeat crematorium’), that infamous dourness (‘the uptight and bleak characteristics which are meant to dribble off the Scots like cold rain off a nettle’). She wonders how true that stereotype really is, discovering in Tallinn that the Estonians are a lot more physically buttoned-up, while in Thessaloniki a group of Greek writers holed up in a rainstorm worried that they, too, might end up like the Scots ‘if this lousy weather continues’.

It’s the weather that ‘makes us bowed and cautious for most months of the year’, Kennedy decides. After all, ‘beach lolling, casual linens and al fresco nudity’ may be OK in the Med, but in Nairn or Portobello? They ‘do not make for a lovely weekend. They make for a Sunday night in A&E.’

Comments