No one had prepared the Allied soldiers, as they began their invasion of the Reich early in 1945, for what they would find. The discovery by the Soviets of the extermination camp of Majdanek in July 1944, and Auschwitz in January 1945, had not really registered, not least because they had been partly emptied and demolished by the retreating Germans. In any case, no one – not the International Committee of the Red Cross, nor the Vatican, nor the British and American governments – had been able, or wanted, to believe what they had been told. The scenes of slaughter and horror that awaited the British, Canadian and American troops were unimaginable.

Peter Caddick-Adams devotes considerable space in his detailed account of the last 100 days of the war in the west – a period he considers to have been somewhat overlooked by historians – to what the Allied forces encountered as they pressed west. Understanding what, ‘materially and spiritually’, Germany had descended to was like ‘conducting a series of archaeological digs’. One by one, including concentration and extermination camps, torture and detention centres and the places where the estimated12 million slave labourers were kept, some 45,000 camps came to light.

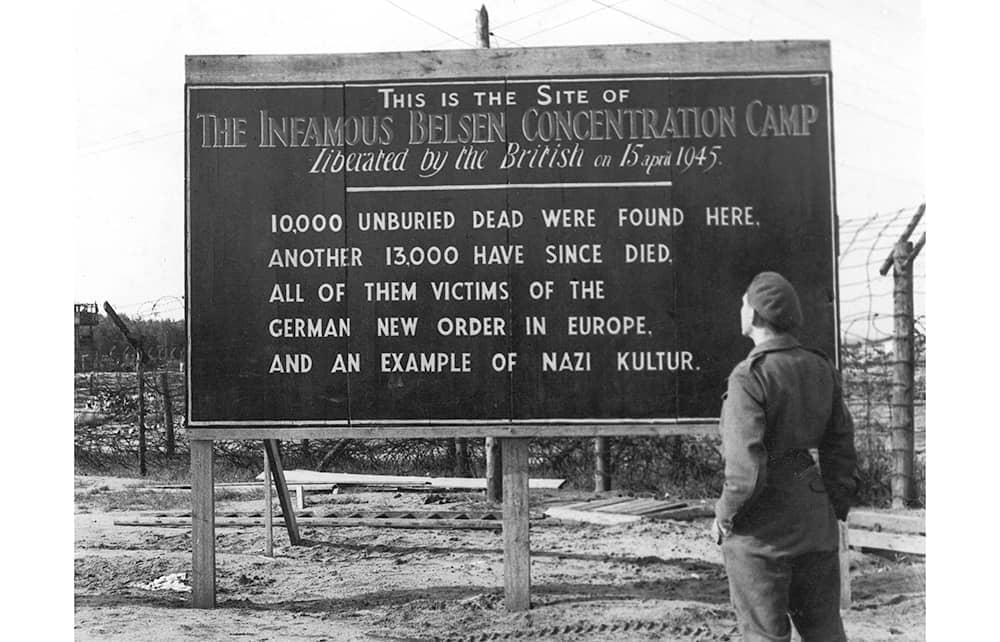

The sheer number was like a ‘sledgehammer’. Neuengamme alone had 99 satellite camps. Fighting their way forward against an enemy keen to hide evidence of their crimes, Allied soldiers found piles of unburied corpses, skeletal and dying survivors, typhus and trains full of rotting bodies. The stench was overwhelming. In Belsen, liberated on 15 April, 60,000 profoundly emancipated people, from 20 different nationalities, lay dying. As the camps were freed, the soldiers were ordered to look closely, so as to understand what it was they were fighting against. Come to grips with the Germans, they were told, and ‘kill lots of them’.

One by one, some 45,000 camps came to light as the Allied forces pressed west

Some four million soldiers, in seven Allied armies, took part in the invasion of the western Reich. The fighting was bitter all along the front until the very end. In the middle of the Ardennes, in January 1945, General Patton wrote in his diary: ‘The Germans are colder and hungrier than we are, but they also fight better.’ The advancing Allies were overwhelmed by confusion, shelling, mines and panzers; all were ‘cautious, many were tired and no one wanted to be the last to die’.

1945 is a meticulous reconstruction of their slow, costly progress into central Germany, following in the footsteps of individual companies, corps and divisions. There are no Russian voices and very little about the air force, the author having decided to write only about the ground troops. Interspersed among tactics, battle orders and the performance of individual weapons are descriptions of the men felled by frostbite, trench foot and pneumonia, and the horror they witnessed.

Caddick-Adams’s focus is on the soldiers, whose memoirs and diaries he has mined, and on the friendships and animosities between the commanding officers and the way their rivalries played into their decisions. Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the general staff, spoke of Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces, as having ‘no real direction of thought, plans or energy… just a co-ordinator’. Patton is mercurial and fiery and General Montgomery is a commander ‘about whom no one felt neutral’. There are pen portraits of a number of GIs ‘who had bubbled to the surface as natural leaders’.

It was a terrible 100 days. There were wide, fast-flowing rivers to cross – the Rhine alone ran for 820 miles through six countries – along with fortresses to storm, towns to liberate, networks of defensive bunkers, trenches, barbed wire and minefields to negotiate: a vast landscape of craters carved by shells and filled with bodies of humans and animals. The corpses of Germans suspected of malingering, cowardice or desertion hung from trees. SS men caught by their former prisoners were sometimes bludgeoned to death while the Allied soldiers stood by or, exhausted and revolted by what they had seen, went on orgies of looting and destruction of their own. The effect of the fighting on the civilian population is left largely to the reader’s imagination, but it is not hard to think what they must have felt when their farmhouses were demolished to provide hardcore to make waterlogged fields passable by tanks and whole villages were reduced to scorched earth.

At 6.30 p.m. on 4 May 1945, on Lüneburg Heath, representatives of the ‘German forces in Holland, in north-west Germany, including all islands and in Denmark’ agreed to ‘cease unconditionally all hostilities on land, on sea and in the air’. The atmosphere, noted one officer who was present, was of ‘a school prize-giving or village fete where award-winning vegetables were being judged’. Four days earlier Hitler had shot himself in his bunker in Berlin; Eva, his wife of less than 24 hours, had taken poison. The first part of the second world war, the conflict in the west, was over. Between D-Day and VE Day, the western Allies had lost three quarters of a million men. Of Germany’s great army, some three and a half million were dead and many more missing. It was mainly women who were put to work to clear up the ruins of the Third Reich, now split into four zones of occupation.

Caddick-Adams then follows the fate of the surviving senior commanders – the Allies to the continuing war in Japan or back into civilian life, the Germans to their war trials, executions or long prison terms. In Berlin alone, 7,000 people – generals, admirals, senior police and SS men – committed suicide.

1945 is an impressive work, lively, informative and comprehensively researched, if somewhat daunting at more than 600 pages and with a 15-page ‘military tool kit and glossary’. But as a picture of the unrelenting awfulness of the closing months of the war, as the horrors of the Nazi atrocities unfolded before the soldiers’ eyes, it stays long in the mind.

Comments