The Anne Frank story continues

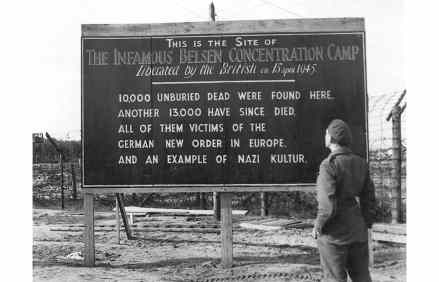

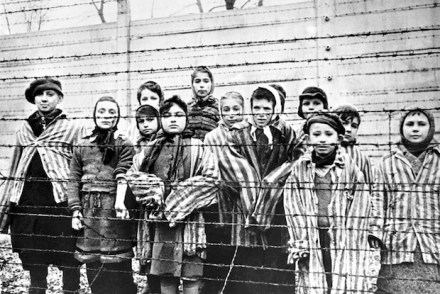

The first time a friend told me that Hitler had the right idea about the Jews I was six. Most of my classmates agreed, and quoted their parents in evidence – from which I conclude that anyone who suggests that they don’t understand how the Holocaust happened is either a fool or a liar. It was a team effort by popular demand. If the Germans had won the war, no one would have felt bad about it. But the Germans lost. How awkward. Anne was freezing, starving and dressed in rags. ‘They took my hair,’ she said. Then she disappeared It became necessary to convince non-Jewish Europeans that mass-murdering Jewish