I was sceptical when the lady on the bus to Reading town centre told me that her father knew Liszt. Who wouldn’t be? This was a long time ago, mind: probably 1980, and I was on my way into school. I think our conversation started because I was reading a book about music. She was old and tiny, wearing a luxuriant wig. She introduced herself as Mrs Ball but her accent was unmistakably German. Even so, Liszt had been dead for nearly a century. Could it be true?

‘Oh, my father knew everyone,’ she said. ‘Richard Strauss was a great friend. And dear Bruno Walter. He lived in our house, you know. They were wonderful days – we were surrounded by the finest music.’ But by this stage the Number 26 had reached its destination; Mrs Ball had to curtail her memories of musical soirées in pre-war Berlin as we were dumped in front of the Butts shopping centre.

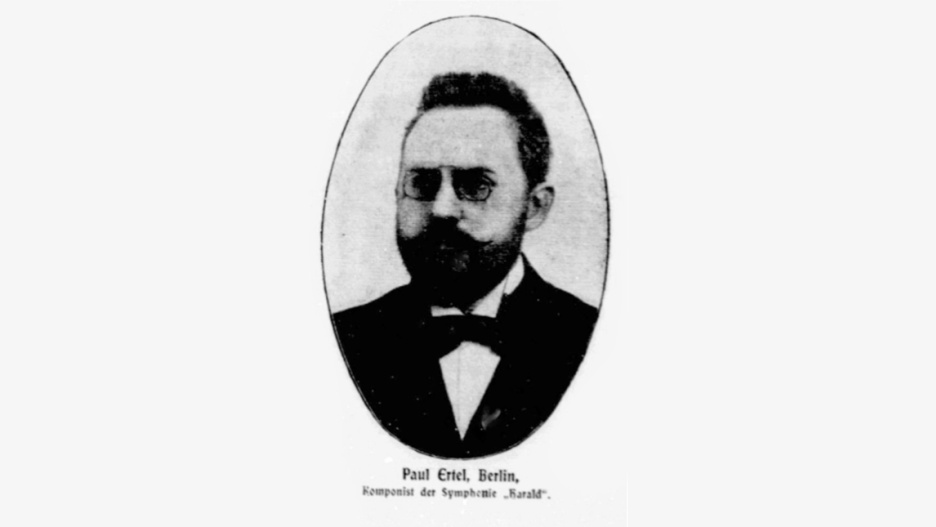

There were a couple more brief chats on the bus, during which I learned the name of her father: Ertel. He’d been a composer, she said, but no one played his music any more. That was the only time she looked sad. Mostly she was girlishly excited to be asked about her musical idols, of whom the greatest couldn’t possibly have met her father. ‘Le divin Mozart!’ she exclaimed, wriggling with delight on the beer-stained seat.

Later, when I was at university, Mrs Ball visited our house: she and her frail English husband lived a few doors away. She was sweetly enthusiastic about my ham-fisted performance of a piece from Schumann’s Kinderszenen, but by that stage I was too self-absorbed to pay her much attention. She celebrated her 80th birthday about that time and then we moved away. And ever since I’ve regretted not asking her more about her life in Germany, and especially her father’s connection with Liszt.

Not one piece of music by a composer championed by Mahler and Strauss has been commercially recorded

Years later, I tried to hunt down Ertel, but he wasn’t in Grove or any other reference book. Nor could I find him in the early days of search engines, and I gave up. Then two weeks ago, on a sudden impulse, I typed in the name and there he was on German Wikipedia: Jean Paul Ertel, who was born in Poznan on 22 January 1865 and died in Berlin on 11 February 1933 (so he only had to endure 13 days of Hitler). He studied law, then devoted himself to writing music – the symphonic poems Maria Stuart, Balsazar and Der Mensch, a string quartet on Hebrew melodies, and his best-known work, the Concerto for Solo Violin complete with a sadistic four-part fugue.

According to an entry in the Neue Deutsche Biographie of 1959, ‘important conductors such as A. Nikisch, G. Mahler, F. Weingartner, Ferdinand Loewe and Richard Strauss campaigned for the composer, so that Ertel’s symphonic poems often appeared in concert halls around the turn of the century’. Mahler! My bus companion hadn’t mentioned him. And, yes, Ertel had indeed been a pupil of Franz Liszt. I felt guilty for suspecting that Mrs Ball had gilded the lily.

But there’s an obsessive streak in me that insists on absolute proof. (For example, I own a tobacco jar that belonged to Charles Dickens: his granddaughter gave it to my grandmother, but it drives me mad that the documentation is missing.) How could I show that Mrs Ball of Whitley Wood Road, first name unknown, was once Fräulein Ertel? I spent hours on Ancestry.com but clearly the answer lay in German archives. I mentioned this to my German-speaking friend Jon Anderson and two hours later a birth certificate popped into my inbox, for one Ilse Ertel, daughter of Jean Paul, born 1899. But that seemed a couple of years too old and there was no Ilse Ball in the Ancestry.com records.

I was about to throw in the towel when I typed ‘Ilse Ertel’ into Google – and there it was. A scan of a British Red Cross document from 1945 urgently asking about Ilse’s whereabouts, from her younger sister Eva Ball, née Ertel, of Reading, Berkshire. And that enabled me to establish that Eva was born in 1902, which tallied exactly with her 80th birthday, and died in 1993.

So after 40 years my little mystery was solved. But it’s still puzzling that, so far as I can discover, not a single piece of music by a composer championed by Mahler and Strauss has been commercially recorded. You can hear a couple of electronically generated versions of Ertel’s symphonic poems on YouTube and I’m afraid they’re not much fun: think Reger without the light touch. Yet the Concerto for Solo Violin was a sensation in his day and we know that the great Henryk Szeryng owned a copy. At the time it was one of the most difficult violin pieces ever written. If some young virtuoso wants to startle a competition jury, then why not resurrect Ertel’s finger-busting pyrotechnics?

Comments