It was not a war to end all wars, writes James Howard-Johnston at the start of this illuminating and thought-provoking book about the confrontation between the empires of Rome and Persia that began at the start of the 7th century and lasted the best part of three decades; it was not even a war with ambitious goals. The ‘last great war of antiquity’ started when the Shah of Persia, Khusro II, decided that the assassination of an unpopular emperor in a palace coup in Constantinople gave him the excuse and the window he needed to try to put right a punitive settlement that had been imposed on Persia a decade earlier. It was miscalculation that changed the world, writes the author, the start of a war whose consequences were so profound that it serves as ‘the final episode in classical history’.

Howard-Johnston, an Oxford historian (and this reviewer’s former doctoral supervisor many moons ago), writes with verve and precision to tell the story of the momentous events that took place between 602 and the start of the 630s. It was a time of high drama and high stakes. Persian forces cut through Roman defences across the Near East, capturing the province of Egypt, a crucial source of wheat for the Mediterranean economy. Cities fell like dominoes, including the holy city of Jerusalem in what the author describes as ‘the most sensational item of news from the Middle East’ in the whole course of the war.

More was to follow as the Shah’s army bore down on Constantinople, which it then subjected to a siege in 626 that many inside the city believed presaged the end of time when the seas would boil and the sky would be torn apart.

In one of the most extraordinary rear-guard actions in history, the Emperor Heraclius rallied his forces, repelled the Persians and out-manoeuvred them diplomatically by forging an alliance with the powerful confederation of nomads under the leadership of the Turks who controlled land, manpower and cavalry to the north of the Black and Caspian Seas. To secure the alliance, Heraclius had to treat the Turkic ruler as an equal, and promised his daughter in marriage, showing a portrait of her to his future son-in-law to entice his support. These were desperate measures fit for desperate times.

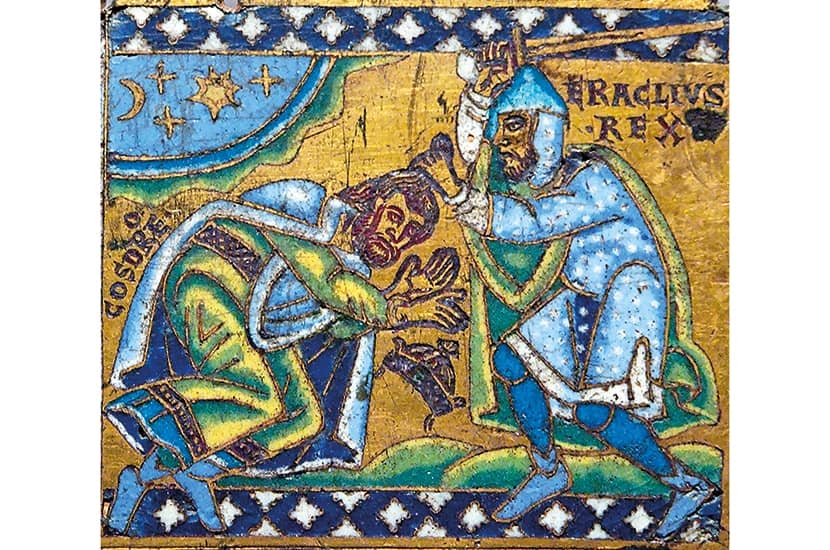

The reversal of fortunes was spectacular. Just a few months after Constantinople had been surrounded and the Roman empire was on its knees, it was the Persians who were teetering on the brink. Now the Roman army was on the offensive, inflicting a breathtaking defeat of the Persians at Nineveh, capturing Dastagerd and the contents of Khusro’s favourite palace. As the Romans bore down on Ctesiphon and threatened the city, the Shah was deposed, plunging Persia into anarchy. Although Heraclius did not deliver the knock-out blow with an assault on the capital, by 630 he had won the war decisively. Victory had truly been snatched from the jaws of defeat.

Celebrations were staged in Jerusalem to demonstrate that the turnaround was not only inspired by the brilliance of the emperor but had divine backing. The war had been fought in a fog of religiously inspired propaganda on both sides — something that was not lost on those observing from a safe distance. For the main beneficiaries of this war, as it turned out, were not the Romans, but a disunited, peripheral collection of Arabs who had gathered under the leadership of a man who also claimed to have divine inspiration. The sequence that followed this great war was to see the Persian empire and much of the Roman world swallowed up by the Arabs, sweeping all before them with their Islamic faith to create a world that marked a decisive break from the past.

Howard-Johnston leaves no stone unturned, navigating the complex and sometimes contradictory accounts written at the time and retrospectively with pinpoint accuracy. That matters, for this period contains more than its fair share of red herrings — partly because of the ferocity of the conflict with the pen as well as with the sword. Heraclius was not averse to using the dark arts to stir up anger among his troops and subjects, issuing dodgy dossiers and making sure fake news circulated about his rival to inflame passions.

Some regions and periods seem to be able to support a near-endless number, range and variety of new treatments. Late Antiquity (broadly the period from 300-700) can sometimes struggle to break the shackles of the academic world, where it is currently enjoying something of a boom. This book is certainly worth the effort, and readers will come away impressed not only by the big headlines of an epic story but by the detail with which it is told that draws on subtle readings of an astonishing range of primary sources. This is first-class scholarship, delivered with panache and style. Much to be enjoyed by those who give it a try.

Comments