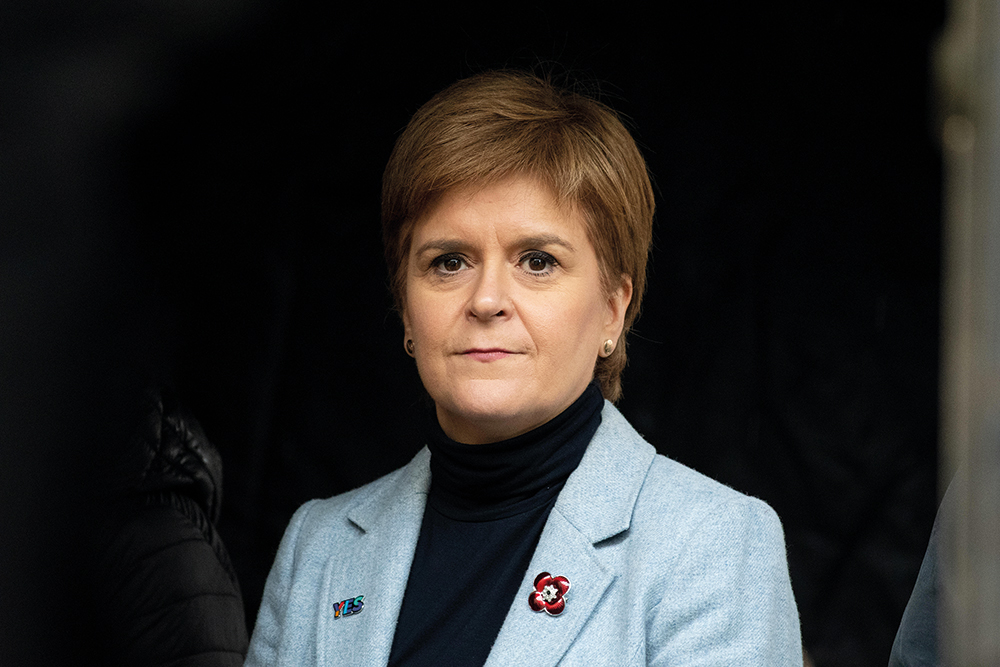

Nicola Sturgeon has all the usual things she wants to achieve in her memoir: rumours to scotch, a legacy to spell out, and so on. But the most important thing to the former first minister seems to be telling her readers that she is in fact not Nicola Sturgeon. The ‘seemingly confident, combative woman who dominated Scottish politics for more than a decade, unnerved the Westminster establishment, helped lead Scotland to the brink of independence and steered it through a global pandemic’ (her words) is in fact an outfit that the real author of Frankly has been wearing for a very long time. She seems quite keen to cast it off.

In 1992, she says, ‘Nicola the soundbite, facsimile politician was born’. She was standing in Glasgow Shettleston for the SNP, a strikingly young candidate who was still finishing her final year in law at Glasgow University. The ensuing media attention meant that how Sturgeon came across really mattered; and ‘since I was too young to really know who I was, I presented to the world an image of what I thought a politician should look and sound like’. She copied the mostly middle-aged men around her, and ‘developed a very serious and austere persona’ and became a ‘personality-free zone’.

Until this point in the book, the Nicola Sturgeon we have been getting to know is a painfully shy, introverted, bookish girl. She uses the word ‘terrified’ repeatedly, and is driven by a fear of being found out. Even once clothed in the persona that the rest of the world recognises, she continues to fear being found out as a politician, repeatedly working herself too hard and not – she later reflects – enjoying what she’s doing. In fact, in the closing pages of the book, she says the tribulations of the end of her time in frontline politics have meant she has ‘learned to dance in the rain’. Perhaps this ‘live, laugh, love’-style turn of phrase sounds worse because it is so unlike the Sturgeon most of us know, even at the end of her attempt to revise that.

The tribulations don’t come until the later chapters. If you’re looking for drama, and particularly the account of how she went from being Alex Salmond’s protégé to the person he blamed for what he died believing was a conspiracy to destroy him, then you’ll have to wait. Frustration with Salmond pops up from time to time in the earlier chapters: he didn’t engage soon enough with the Scottish government’s Independence White Paper, and irritated Sturgeon by phoning her from Hong Kong to tell her ‘what a great afternoon he’d just had watching horse-racing, and to give me some “tips” for FMQs. He was far from sober and not a word he said was of any use to me’. But really the irritations and disappointments are mostly what you’d expect from a long working relationship between two very different people in a high-pressured environment. The collapse when it comes is vertiginous and – still to Sturgeon – baffling.

The one thing Sturgeon doesn’t seem particularly regretful about is that Scottish independence hasn’t happened

A striking thing about this beautifully written memoir is that Sturgeon really does try to remain dignified throughout. There is a deliberate (and to some rather disappointing) lack of gossip or bitchiness. Mostly when these two vices do crop up, it’s when she is repeating a rumour that someone spread about her so that she can demolish it. Most of these rumours are of a sexual nature, and she reflects – not unreasonably – that men just don’t have to deal with the kind of innuendo and suspicion that women in politics do.

That dignified approach includes a deeply painful passage about suffering a miscarriage. As with the rest of the book, Sturgeon is open and vulnerable about the loss and grief she still feels. But she tells this particular story in a spare, short way. It is all the more moving for that.

She is also anxious to show she has meditated on all her mistakes and her failings in any scandals or rows. The longest reflection, other than on what went wrong with Salmond, is on how she made such a mess of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill. She opens by remarking that it now ‘seems hard to believe that political consensus once prevailed on this issue’. She describes the Holyrood debate on the legislation as ‘deeply unpleasant’. At the time, she seemed to have decided that she was pursuing the right course of action, and critics were wrong. In this book, she takes a much softer tone. When she tries to weigh up whether the ‘toxicity’ could have been avoided, she says there are things she could have done better.

That turns out, in the long passages that follow, to be really thinking her way around the issue for the first time, properly considering the concerns of critics who she now recognises were sincere in their worries about women’s safety. She is, though, careful to single out J.K. Rowling for wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan ‘Sturgeon, destroyer of women’s rights’, which she says ‘marked the point at which rational debate became impossible’ and ‘made me feel less safe’. About this, as about so many other aspects of her political career, she remains palpably hurt.

The one thing she doesn’t seem particularly emotional or regretful about is the reality that the very thing that drove her into politics – Scottish independence – hasn’t happened. She insists that she still believes it will in her lifetime. Or at least in the lifetime of the real Nicola Sturgeon.

Watch Ian Blackford and Michael Simmons debate Sturgeon’s legacy on SpectatorTV:

Comments