Of all the photos of artists in the studio, the one of Glyn Philpot being served a martini by his white-jacketed Jamaican model Henry Thomas must be the strangest. Taken to publicise his 1934 exhibition, it would be unthinkable now but in the circles Philpot moved in at the time it might, I suppose, have been viewed as cool.

For 20 years Philpot had been London’s leading portraitist, a position he inherited from Sargent. His sitters included admirals – four during the first world war – and King Fuad of Egypt, who commissioned a ‘dignified, decent, usual and rather sumptuous’ portrait from the 38-year-old artist for £3,000 in 1923, the year he was elected an RA. It was not his best work. He was less comfortable with male authority figures than with writers, actors and society hostesses, who queued up to be flattered by his brush. ‘All the papers are raving about P…,’ a friend reported in 1910. ‘Everyone is rushing to be painted like sheep.’

There’s a chill about Philpot’s paintings of women; it’s obvious that he much preferred painting men

His success financed a studio in Tite Street, an arts and crafts manor in Sussex and a chauffeur-driven car, but by the 1930s he had tired of portrait commissions; his full-length of Loelia, Duchess of Westminster – who as Loelia Ponsonby had been hailed by Tatler as the ‘squadron leader of Society’s Young Brigade’ – on her marriage to the 2nd Duke of Westminster in 1929 was the last grand manner portrait he undertook.

Perhaps the shine had already come off the Bright Young Thing – the marriage would be a disaster – but Loelia’s portrait is a little insipid. Philpot had taken on Sargent’s mantle without his swagger. His satins shimmer and his flesh tones are perfection but his formal portraits, especially of women, lack panache. Landed patrons liked them because they slotted straight in among the Van Dycks, but in Pallant House Gallery’s new exhibition – the first major Philpot show for nearly 40 years – they look rather lifeless. There’s a chill about his paintings of women, even his sisters; it’s obvious that he much preferred painting men. Just read his lips: the women’s are pursed, the men’s are kissable.

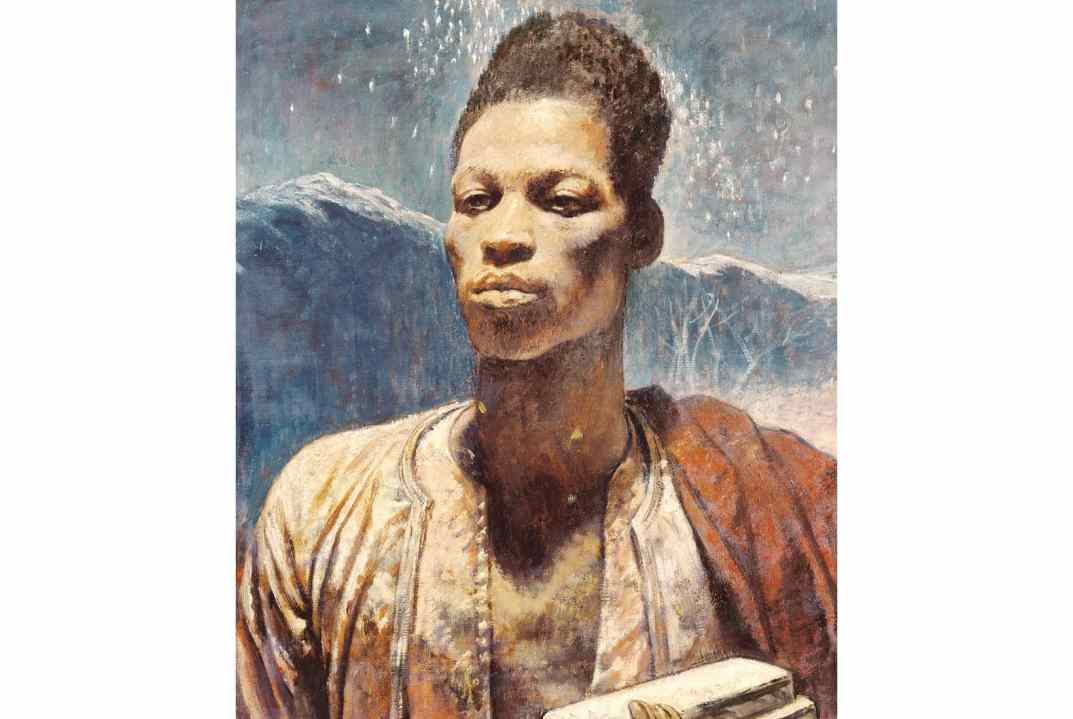

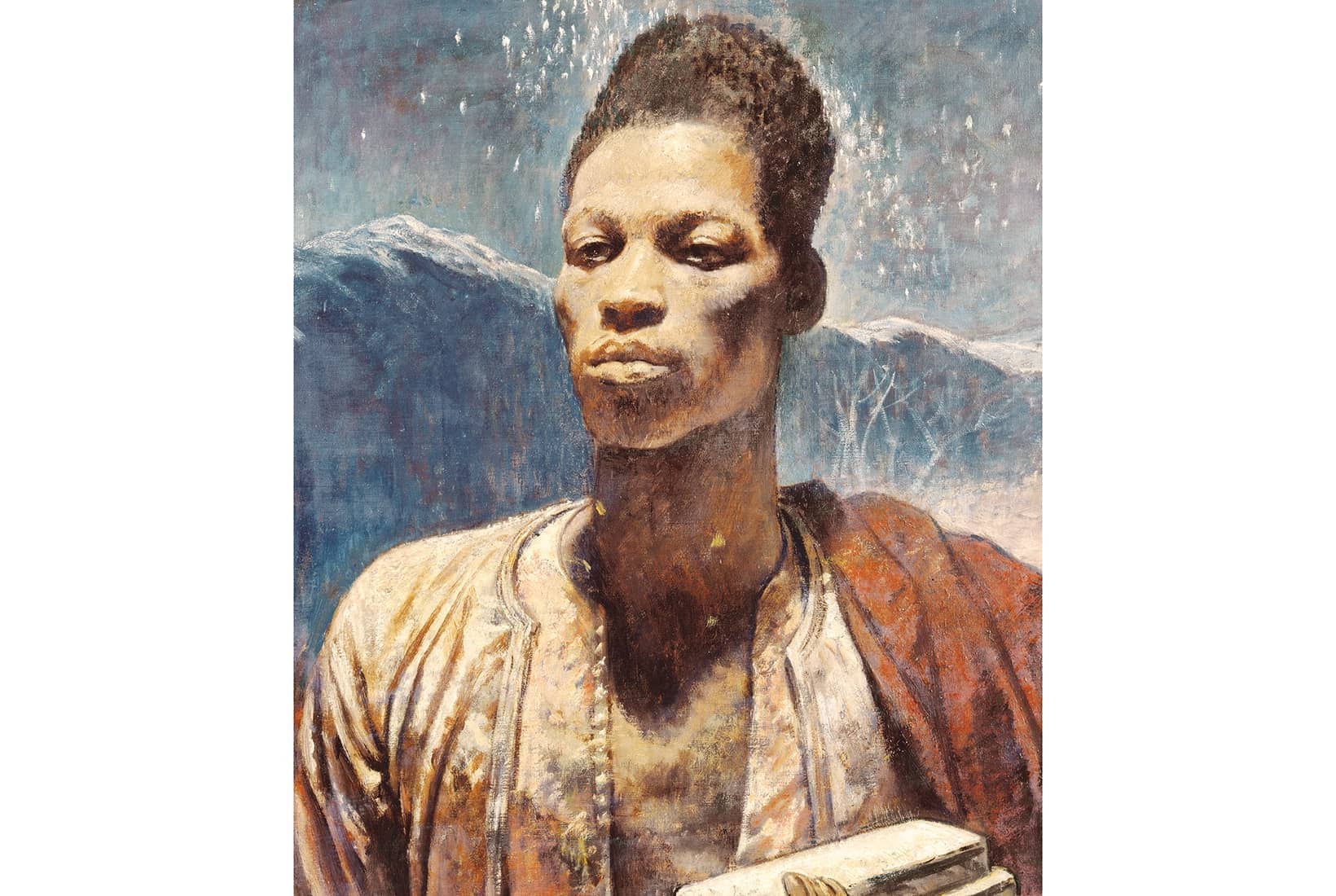

As an antidote to bloodless duchesses, Philpot went in search of young working-class men to cast in ‘subject’ paintings. An early find, George Bridgman, was gorgeous in a carnal, mildly dangerous way; Philpot drew his portrait in Raphaelesque red chalk in 1924 and posed him in ‘A Street Accident’ (1925) like Mantegna’s Dead Christ. (A Catholic convert, Philpot flirted – sometimes outrageously – with religious subjects.) Unusually, he also sought out black models. A few, like Paul Robeson, were famous but most, like the handsome Ethiopian ‘Billy’ in a dramatically backlit portrait of 1912, were unknown. In Paris, where Philpot moved in 1930, the Caribbean cabaret scene was a source of models such as the suave Martinican Julien Zaïre, stage name Tom Whiskey – who sat in a tux – and Félix, doorman of the Tagada nightclub, who posed with a hibiscus flower behind his ear. But Philpot’s great and lasting inspiration was the Jamaican Henry Thomas.

Thomas turned up, propitiously, in the National Gallery. A stoker on a merchant ship from New York, he had been found by Oliver Messel in 1928 roaming the galleries after missing the boat home while drunk. Philpot took him in as a model and live-in servant, a role that lent the relationship respectability. There’s no evidence that they were lovers; Philpot seems to have viewed himself as in loco parentis. He paid Thomas a retainer, covered his health stamps and packed him off to rehab to cure his drinking. Writing from abroad to his sister Daisy in 1936, Philpot begs her not to send Thomas away if he’s difficult: ‘I find I am so attached to the idea of him, I should feel quite lost if he were gone.’ Thomas, similarly lost without Philpot, went off the rails after the artist’s unexpected death aged 53 in 1937.

The infinite sadness of Thomas’s inward gaze in a final portrait of that year recalls Sam Selvon’s description in The Lonely Londoners of his Trinidadian hero Moses sighing ‘a long sigh like a man who live life and see nothing at all in it and who frighten as the years go by wondering what it is all about’. As a homosexual, Philpot knew what it was to be an outsider; he once described himself to Karen Blixen as ‘an exile everywhere’. In his only self-portrait from 1908 he looks oddly hesitant, less like an artist than the head waiter of a failing restaurant.

After coming out as a modernist in the 1930s, Philpot wrote to Daisy: ‘I feel the paint will explode on the canvas.’ It didn’t. He exchanged his Old Master glazes for modern brushwork, but his approach to painting remained curiously guarded – modernish rather than modernist. One wonders whether he would have dropped his guard if he’d been able to come out as gay.

Comments