Last summer, in the bc era, I took my then three-year-old to a new group play session: ‘Lottie’s Magic Box.’ Off we trooped in the usual north London fashion: child on scooter, imperious and unmoving, hauled along by mother in the role of husky. Micro, purveyor of scooters to the middle-classes, sell colour-coordinated leads especially for this purpose. It sometimes crosses my mind that they should also sell whips for the pre-schoolers to brandish.

The map on the event website directed us to what looked like an office block in a park and as we opened the door, any wisps of hope that this might be an uplifting hour of bonding and fun evaporated. The room was the size of a police holding-cell, and already there were mums banked up around three of the walls, self-medicating with iPhones. In the middle of the room, the mass of Rubys and Oscars milled like restless cattle, grinding rice cakes underfoot.

Stand-up comics complain about tough gigs but no audience of adults can match the brutality of a pre-school crowd. People say that even babies have a rudimentary moral sense. I say, in my experience, under-fives are entirely without mercy. One misstep from the entertainment, a moment of weakness, and you’re toast. ‘Can I tell you something?’ said a small girl to me recently, after I’d spent half a day playing with her. ‘I don’t think you’re fun at all.’

Against the fourth wall stood Lottie, a slight thirtysomething, and a small wooden box. No costumes, no lights, no glitter ball, no snacks, no pictures or puppets, no bubble machine in sight. Lottie, I thought, you’re dead. But as it happened, I was wrong. And as I contemplate the months of socially isolated single-parenthood ahead — as I feel the walls of our kitchen closing in — the thought of that hour with Lottie gives me hope.

All Lottie did was set a scene. She’d lost a lion called Arthur, she told the sceptical-looking midgets, and asked: ‘Would you help me find him?’ It was risky, as opening gambits go, but the rabble bought it, and then off they all went on an imaginary lion hunt, my son among them, round and round on that square of lino. They put up their imaginary umbrellas in the imaginary rain, waded through a river, hurled nonexistent sponges at invisible enemies, and ducked when the enemy fired back. Some of the little ones shivered with cold though it must have been 40 degrees in the room.

Lottie had chutzpah and command — she believed in her own story — but it was the children who took me by surprise. Un-camouflaged by plastic — no Paw Patrol figures, no Peppa Pig, no trains — prop-free, their ease with fantasy seemed spooky. Some of them could barely talk. How, why, can they inhabit and understand invisible worlds? What sort of creatures are we?

Some communities around the world see a child’s propensity to make-believe as suspicious, possibly demonic

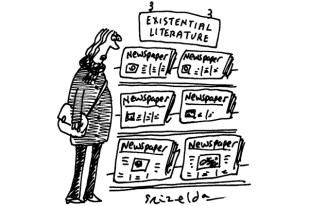

There doesn’t seem to be much literature on the meaning of make-believe. Most psychologists assume that children play ‘pretend’ as a way of practising to be grown up, and leave it as that. Stuff and nonsense. Do all two-year-olds, like Billie Jo Spears, dream of having a small café? No they don’t. It’s the act of imagining that’s fun, not the endless invisible cups of tea. Even tiny children quite naturally both narrate a story and inhabit the characters they invent; they endow socks, rocks and trees with personality and see things from their point of view. The children entering into Lottie’s imaginary world weren’t practising to be grown-ups, they were doing it for the same reason young crows tumble about in the wind: because they’re born to do it, because they can.

The only decent book I can find on the subject, The Creation of Imaginary Worlds by Claire Golomb, says that there are communities around the world who see a child’s propensity to make-believe as suspicious, possibly demonic. The Mayans of the Yucatan in Mexico stop their children inventing fantasies and instead direct them towards gardening or sport. In Kenya and in India, among the Bedouin of the Middle East, says Golomb, pretend play is frowned on as wasteful. What’s interesting is that even so, the kids find a way — turning pebbles and sticks into characters. In Texas, I’ve heard, there’s a group of parents who thinks it healthier for a child to simply skip the make-believe stage and move on to the real deal. If a kid points a stick and shoots, just get him a gun. Simple.

Golomb also mentions just in passing that for the most part, like it or not, and without any adult encouragement, boys worldwide make-believe cheek-to-carpet in character as a car or train, whereas for the most part (with exceptions) girls enjoy playing house — this remains true whether or not the parents believe in gender as a biological fact.

Right at the end of her hour, Lottie made her only false step. Alfred the lion, she suddenly said, was toy-sized. The thigh-high mob turned suddenly to look at her, the light of fun suddenly gone from their eyes. Just as there are strict rules to fantasy worlds in fiction, so the world of pretend has its codes. We all knew what Alfred looked like. Alfred was a full-size lion. We’d been looking for him for an hour — he wasn’t Lottie’s to shrink. Once you invite people into your fantasy, once it’s shared, it becomes real.

spectator.co.uk/podcast - Mary Wakefield and children’s author Piers Torday on children’s worlds of make-believe.

Comments