The last Yana-speaker in the world died in 1916. When Ishi was born, the Yana were still a small but healthy collection of tribes ranging the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, where they lived off what they could hunt and the salmon they caught in the rivers. But gold had been discovered in California and every year tens of thousands of settlers were arriving to stake out a claim. When Ishi was four years old, there was a massacre of Yana people near what’s now Mill Creek; Ishi’s father was one of the people killed. The last few survivors disappeared into the hills. The white settlers never encountered them again; as far as they knew the Yana had been wiped out.

Forty-four years later, Ishi wandered out of the mountains, starving and alone, and into the town of Oroville, where he was arrested and handed over to anthropologists at the University of California. He spent the last five years of his life at the university, where he was displayed as a kind of living museum exhibit: the last wild Indian. He also worked as a janitor; in his spare time he made flint arrowheads, piles of them, in the same way the Yana had been making them for hundreds of years. He never hunted again.

Ishi was not Ishi’s real name. It’s a generic word that just means ‘man’. In Yana society, it’s forbidden to say your own name until another Yana introduces you. But there were no other Yana left to speak his name.

There are several people like Ishi alive today. One of them is a child. In the medieval era, the Livonian language was spoken widely on the Latvian coast, but it’s spent the past thousand years being squeezed on all sides: by the big imperial languages, German and Russian, to the west and the east, which have always been eager to wipe out any minorities in their way, but also by Latvian itself. When a small language community is trying to ensure its own survival in a dangerous corner of the world, it doesn’t always have much patience for its own internal minorities. By the end of the 19th century, there were fewer than 3,000 Livonian speakers in a few scattered villages along the coast; by the time the Soviet Union collapsed there were barely a hundred and by the 2010s there was just one, Grizelda Kristina, a 100-year-old woman who had fled the advancing Soviet forces in 1944 and ended up living in Canada.

Kristina died in 2013 but is survived by a small and dedicated community of language revivalists. They grew up speaking Latvian, but they wish they hadn’t. They want to speak Livonian again and they’re teaching themselves from old textbooks. In 2022, a couple announced that they were raising their child to speak Livonian as a first language: she will be the first person to grow up speaking the language for nearly a hundred years.

In South Africa, Katrina Esau is the last native speaker of Nllng, also known as Nllnǃke. The strange and unpronounceable names are because Nllng is a click language: instead of consonants, it has a repertoire of different clicking sounds. It’s possible that languages like Nllng are a remnant of the very earliest language ever spoken by human beings, which was probably a click language. Nllng is also tonal: the meaning of a word depends on how it’s sung. Katrina Esau is 92. In Australia, Peter Salmon is the last native speaker of Thiinma. While European languages split nouns into genders, Thiinma splits them according to whether they belong to the world of humans, or animals, or the spirits. Peter Salmon is 91. He’s trying to keep the language alive by performing country ballads in Thiinma at Australian bars.

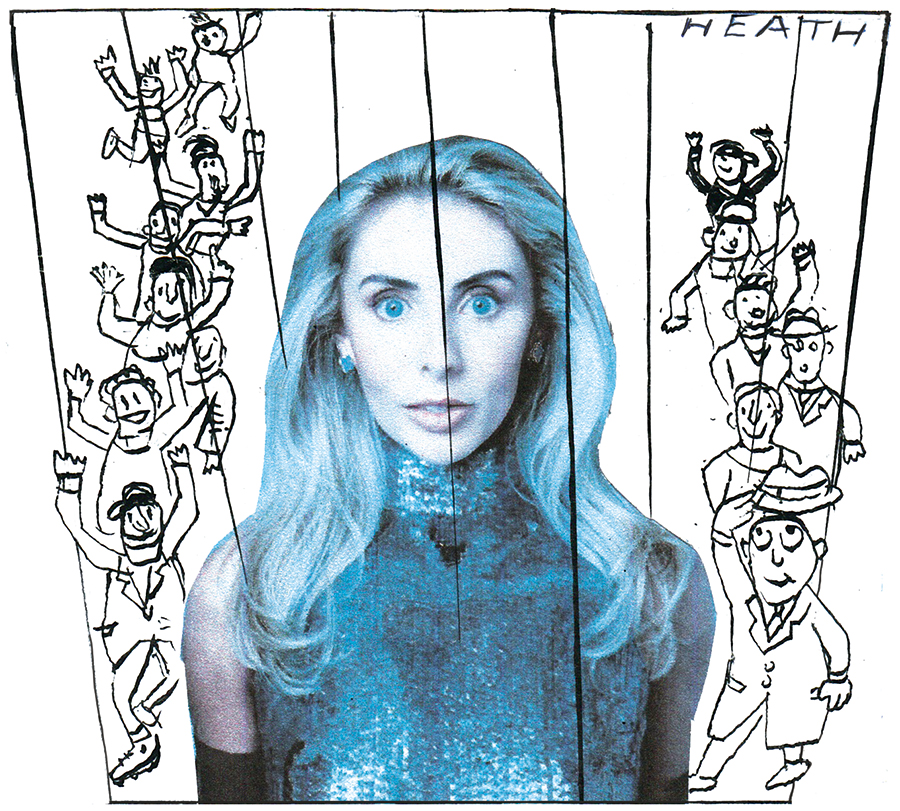

Wittgenstein argued that there could be no such thing as a language spoken by only one person

I find all these stories incredibly sad. Wittgenstein argued there could be no such thing as a language spoken by only one person, because at root language is not a system for connecting objects to sequences of sounds, but a set of rules for a game played between people. It’s not a game you can play alone. In a way, these people aren’t really speaking their languages at all, because the basic unit of any language is the conversation. What they’ve got is one half of a language, and when they’re gone that will disappear too.

But a language dying is not quite the same thing as a person dying. Some languages, like Yana, are destroyed violently along with the people who spoke them, but others just peacefully pass out of history. Small languages get out-competed by big languages that let you speak to more people. The process has probably been going forever, but today a few great imperial languages – English, Mandarin, Spanish, Arabic – are slowly blobbing over the entire surface of the world.

Once, the languages threatened with extinction were tiny, spoken by a few scattered hunter-gatherers or a few villages on the Baltic coast. Now, even big, literary, imperial languages are at risk. If you go to the Netherlands, it’s strangely difficult to overhear anyone speaking Dutch. They all just speak in English. Four hundred years ago, the Dutch publishing industry was the biggest in the world; today it’s on the point of collapse. Why read books in Dutch when everyone speaks English? And France is worried that even French might be next, which is why the Académie Française keeps on insisting that people say mél, short for message électronique, instead of le email.

You can see why France isn’t exactly thrilled by the prospect of its language vanishing, even if it wouldn’t involve any actual harm to any actual French people, and even if it would leave them all slightly better off. Speaking a distinct language has political import; a group with its own language is a people, and one that doesn’t is not. This is why one of the contentions powering the war in Ukraine is what should be a fairly dry academic question: whether Ukrainian is a language in its own right or just a minor dialect of Russian. If you buy a packet of cigarettes in Bosnia, you’ll notice that the warning message is displayed in three languages: Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian. As part of the country’s fragile postwar settlement, the three groups insisted that all their languages get equal billing. It hardly matters that the languages are so similar that what you actually get is the same message printed three times.

But I think what’s really lost when a language dies isn’t anything as minor as people-hood. If a language isn’t just a different set of words for things but a unique game, every language we lose takes away some of the variety of human experience. There are languages that make you use completely different grammatical systems when you’re talking to your mother-in-law, or that distinguish between things you’ve seen personally and things you’ve only heard about. In some languages meaning depends on a rigid word order; in others you can muddle around with a sentence however you want, and it’ll still make perfect sense. The world takes on a slightly different shape if you’re speaking a language with multiple past and future tenses, like Luganda, or one like Malay, with none.

This is what made visiting Voiced, the Barbican’s festival of endangered languages, a slightly mournful experience. You could listen to poetry in dying dialects or watch video installations from around the world. There are three speakers of Vasyugan, separated by miles of barren taiga and marshland in Siberia, but you could watch them here sitting in their homes, sending each other voice notes on their phones. You could also hear the chorus of clicks as Tshwa women built a house. The mourning song of the last speaker of Arikapu, rising and falling as she laments the death of her sister, the only other person she could talk to. It all sounded strange and beautiful. But a language is meant to be understood, and I only speak English: I couldn’t understand a word.

Comments