The best moment in the Vienna Philharmonic’s annual New Year’s Day Concert comes after the end of the advertised programme. The conductor gives a tiny gesture, the violins start a shimmer of tremolando, and a ripple of applause spreads through the hall. At this point, if you’re watching with first-timers, they’ll look at you, surprised. Why have they stopped? And you smile, because you know what the conductor knows, what the orchestra knows and what even the audience in the Musikverein — those bejewelled Eurostiffs in their £1,000 seats — knows. We’re about to hear The Blue Danube, and music doesn’t get any better than that.

Well, that’s how it feels to me, anyway. The Blue Danube was the first piece of music I ever loved and nothing I’ve heard since has persuaded me that those opening moments are anything other than musical genius in its purest naturally occurring form. Johann Strauss II lays down that simple background shimmer, and over it he has a horn play the notes of an A major triad: the most basic building blocks of western harmony. Almost without lifting a finger, he’s created a world. Or even a universe: Stanley Kubrick knew precisely what he was doing when he deployed these sounds in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Instantly recognisable, infinitely poetic; in five decades, I don’t think I’ve heard the beginning of The Blue Danube without an involuntary shiver of anticipation and delight.

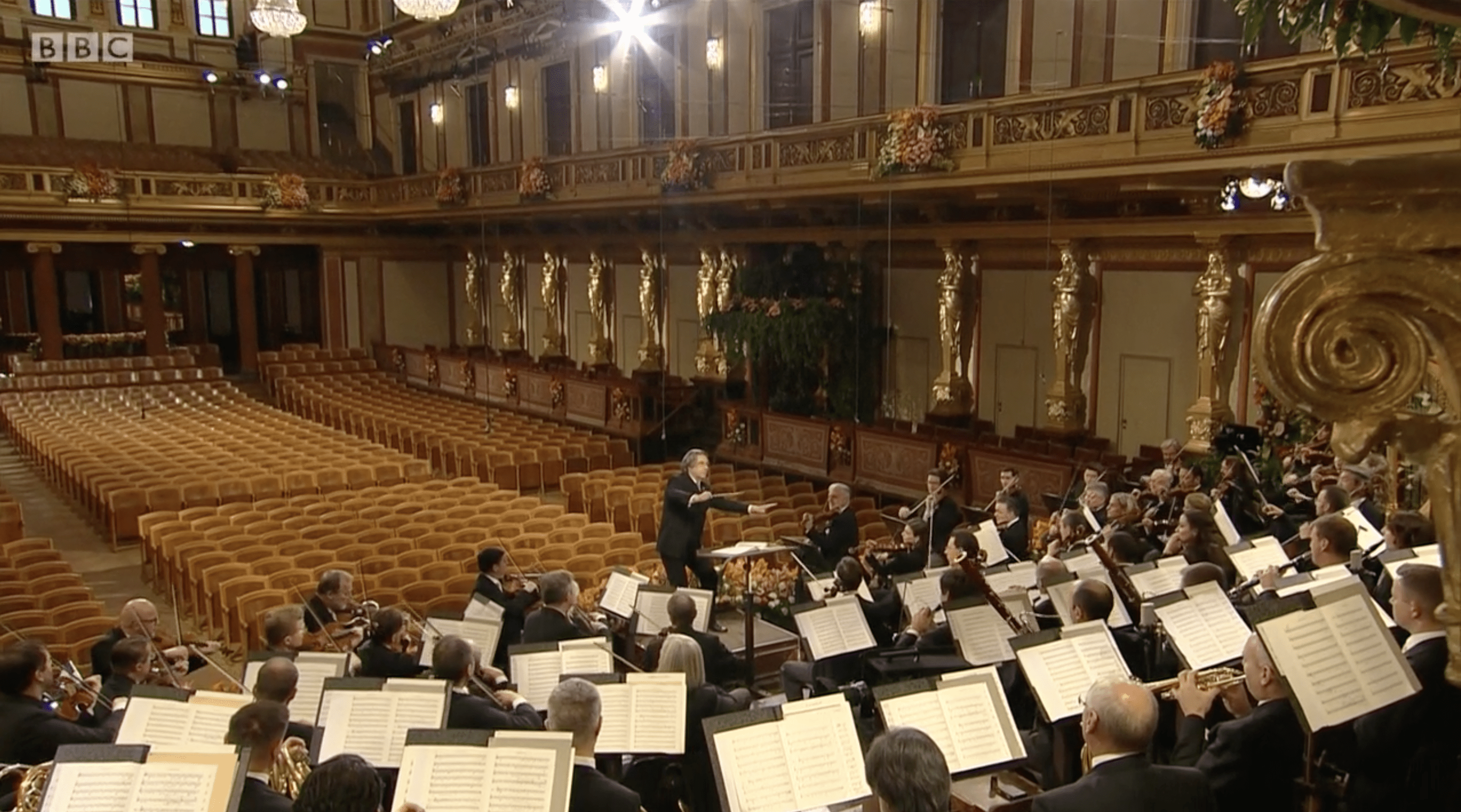

This is exactly the level of cultural pampering you need as you sit amid the ashes of the old year

The absence of that shared frisson was the saddest moment in the 2021 concert. No audience means no applause, though for many the absence of the overdressed Viennese elite, with their curious inability to clap in time to the Radetzky March, will have represented an improvement. I’m not so sure. The whole televised ritual of the New Year’s Day Concert has become strangely consoling. The lingering fades over gilded caryatids and floral displays; the musicians in their grey ties; the pre-recorded segments in which dancers from the Vienna State Ballet disport themselves outside top Viennese tourist attractions — it’s somehow exactly the level of cultural pampering you need as you sit amid the ashes of the old year, head thrumming from that final, ill-advised post-Hootenanny bottle of Aldi cava.

This year, in an empty hall, it seemed trippier than ever, like a sort of pan-European cheese dream. The camera found a dead bird among the flowers; then, with a global audience of millions, lingered on it for a good ten seconds. An interval documentary, produced by Austrian state TV, celebrated Austria’s 1921 annexation of a slice of western Hungary with scenes of smiling peasants and a string quartet playing the former Austrian Imperial hymn. And they say the Last Night of the Proms is problematic. Plus, of course, there were the ballet interludes. Coquettish flapper girls blindfolded a young man in the Adolf Loos House — it was all a bit Eyes Wide Shut. Before lunch, too.

Through it all flowed those lilting melodies, with conductor Riccardo Muti wisely making no attempt to get in the way. The entire orchestra, we were told, had undergone daily Covid tests, and the programme was the usual mix of fan favourites (Roses from the South, Emperor Waltz), Viennese home-cooking (rarities by Millöcker, Zeller and Karl Komzak) and discoveries from the Strauss family’s vast back catalogue. The Schallwellen waltz was new to me; its opening chorale sounding noble on the Vienna brass before the dance melody crashed in on a cymbal-topped crest of sound. Strauss waltzes are often lazily compared to Viennese confectionery, but there’s nothing self-indulgent — no whipped cream — about these lucid, elegantly structured mini-masterpieces. The Strausses give us fresh, organic musical ingredients, superbly prepared and served with grace. There’s still no better sonic hangover cure.

My final live opera of the Plague Year was in the Cotswolds, where Longborough Festival Opera reopened to host Opera Ensemble’s shortened version of Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. Christopher Luscombe’s production — which has also played in London and at the Grange — was spartan, with piano accompaniment and no chorus. The Longborough theatre was built for summer use; it’s unheated, and with the performers forbidden to embrace or touch, a drama driven by illicit passion was always going to struggle to make its full impact. But there’s no denying how good it felt to hear a singer as stirring as Robert Hayward launching into the Prologue, or the authentic theatrical thrill of watching Peter Auty’s raw, predatory Canio close in on Elin Pritchard — a touchingly vulnerable Nedda.

By the time we left, black clouds were massing across the Evenlode valley. A group of opera-goers were sitting on picnic chairs behind their parked car, wrapped in scarves and sipping champagne. It was 19 December on a Gloucestershire hillside and I swear they’d brought an ice bucket. There’s your symbol of hope for 2021, right there.

Comments